Palestinian olive farmers defy Israeli attacks for prized crop

Israeli restrictions, attacks and intimidation continue to hinder the vital olive harvest but Palestinians persevere.

Burqa, occupied West Bank – Palestinian farmers have repeatedly been attacked by Israeli settlers as they harvest their prized olive groves with more than 1,000 trees burned down or damaged, the United Nations says.

According to a report by humanitarian affairs office UNOCHA, there were 19 disruptions “by people believed or known to be Israeli settlers” with 23 Palestinian farmers injured in Israeli-occupied territory since the harvest began three weeks ago.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIsrael’s ‘silent transfer’ of Palestinians out of Palestine

Fighting for Palestine

Palestinians unify as Arab states ‘normalise’ Israel relations

“Each year, the ability of Palestinians to harvest is compromised due to access restrictions, attacks and intimidation,” UN Middle East envoy Nickolay Mladenov told the Security Council this week, calling on Israel to ensure the farmers’ safety.

The olive harvest in the occupied Palestinian territories is now drawing to a close. The much-revered olive tree and olive cultivation are mired in problems: Climate change, outdated agricultural practices, and the Israeli settler violence. Each has taken a toll.

Cultivation of olive trees in the eastern Mediterranean is thousands of years old. Research suggests it started as early as the sixth millennium BC, 8,000 years ago.

“Olive oil is the basis of the home,” a local saying goes.

Proximity to Jewish settlements creates problems for Palestinian farmers trying to reach their olive trees, not only during the harvest but year-round.

Burqa is six kilometres (three miles) from Ramallah but in 2001 the Israeli army blocked the main road connecting the two. The alternate way to get there is to drive for about 30 minutes through the villages of Baytin and Dayr Debwan.

‘No security’

On a recent Friday, dozens of volunteers succeeded in reaching Burqa to accompany farmers to their olive groves for harvesting. The aim was to fend off harassment by the Israelis.

The Israeli army, upon learning of the purpose of the volunteers, set up a roadblock on top of a hill between Dayr Debwan and Burqa and began firing tear gas canisters down below towards the volunteers.

They trekked around the roadblock through the olive groves in the direction of Burqa.

On the walk to the village centre, Al Jazeera met a Palestinian family that was busy harvesting olives. Abdel Baset Moutan and his brother Abu Saleh and their wives and children all gathered.

“The family picks the olives,” 46-year-old Abdel Baset says. “We take time off for a week or two and leave our work and come here to pick our olives.”

Abdel Baset is an Arabic teacher at a school in Ramallah. Abu Saleh is a wage worker also in the city. Economic malaise and the Israeli occupation have pushed many farmers to seek employment away from their land, leading to a decline in agricultural production, especially in the olive sector.

“Agriculture in Palestine is not supported,” says Abdel Baset. “The support goes to the [Palestinian] security services, and unfortunately we are a people that has no security.”

Abdel Baset says the villagers’ sustenance used to be from agriculture and livestock.

Burqa borders two Jewish settlements – Kokav Yacov to the south and Psagot to the west.

“Simply now we are not allowed to herd our sheep near the settlements or the main road,” Abdel Baset says.

‘Chance to harvest’

A few hundred metres away from the centre of Burqa, Israeli settlers erected a tent on top of a hill overlooking the village. The settler tent, the villagers believe, is the nucleus of a new settlement. It is in the middle of an olive grove that has been off-limits to the Palestinian villagers for years.

“In practice, it’s been 10 years or more that we couldn’t reach this land,” Afaneh Moutan, 28, from Burqa told Al Jazeera.

As the volunteers and farmers began making their way up the hill, the Israeli army started firing rounds of tear gas. But the young settlers did not confront the farmers.

The diversion worked. The activists kept the army and settlers busy as the farmers picked their olives.

“Praise to Allah with the help of these young men we got here and the farmers seized the chance to harvest,” Moutan says.

The volunteers call their intervention “faz’aa”, which translates to safeguard.

Khairy Abu Naser, a well-known activist, travelled 70km (35 miles) from Tulkarem to help the villagers of Burqa. The intervention was organised in part by the Palestinian Authority, which is advocating “peaceful popular resistance” against the Israeli occupation.

“We came to stand by our fellow countrymen in Burqa and to protect them from the barbarism of the settlers,” Abu Naser told Al Jazeera.

‘Sacred season’

The season is often celebrated among farmers with a special dish called Musakhan, which has fresh olive oil as its main ingredient.

“This is a sacred season for our people,” says Khairy Naser, 60, from Anabta near Tulkarem.

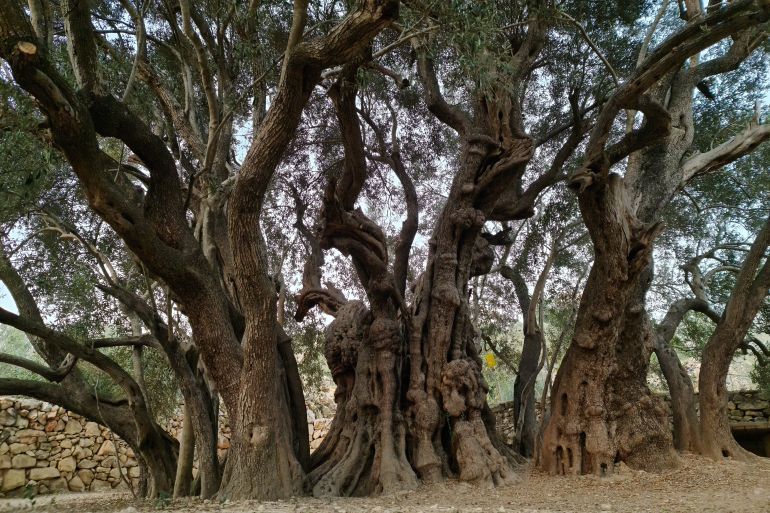

There are more than nine million olive trees in Palestine, and nearly 80 percent of them are more than 100 years old. In the village of al-Waljeh near Bethlehem, there is an ancient olive tree known as al-Badawi. Scientists say its age ranges from 4,000 to 5,000 years old.

But agronomists, such as Fares el-Jabi, say the old age of the trees heightens the “alternate bearing phenomenon” – the tendency of some fruit-bearing trees to yield a high amount of crops in one year and then a much lower yield the following one. Experts recommend rejuvenating the ageing trees to lessen the effects of alternate bearing.

Rejuvenation of an olive tree, however, requires the farmer to cut the main branches to make way for new ones to develop. This means a halt in production for a few years until the new branches start bearing fruit. So farmers tend to avoid it. A compromise solution is cutting one branch and waiting a few years before cutting the next in order not to miss out entirely on production.

But what is needed the most, according to Fares el-Jabi, Palestine’s foremost expert on olive trees, is propagating olive trees from cuttings rather than the more common practice of propagating from seeds. This is a technique that has not gained wide use in the West Bank because of a lack of know-how, and because of the local belief that plants grown from seeds tend to be more resilient. Research shows cuttings yield crops much faster.

“We are so ignorant about what is dearest to us,” laments el-Jabi who is now in his 70s. El-Jabi, a resident of Nablus, has been diligently advocating for better agriculture practices by olive farmers since the 1970s.

“There are no specialists, no research; olive cultivation is not taught in any of the universities in the Arab region.”

Other factors are also affecting the yield. Climate change has wreaked havoc on olive trees since its effects began to be felt 12 years ago.

“Instead of having warm weather during the flowering, we are getting cold temperatures,” el-Jabi says. “Then we get very warm temperatures as the flower turns into fruit.”

Back in ancient times as it is now, the olive trees depend on rainwater.

“It’s all Baal,” Abdel Baset says, referring to the Canaanite god known as the “Lord of Rain and Dew”.