Q&A: At 60, DRC still plagued by colonial mentality

As DRC marks 60 years of independence, Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja talks to Al Jazeera about its past, present and future.

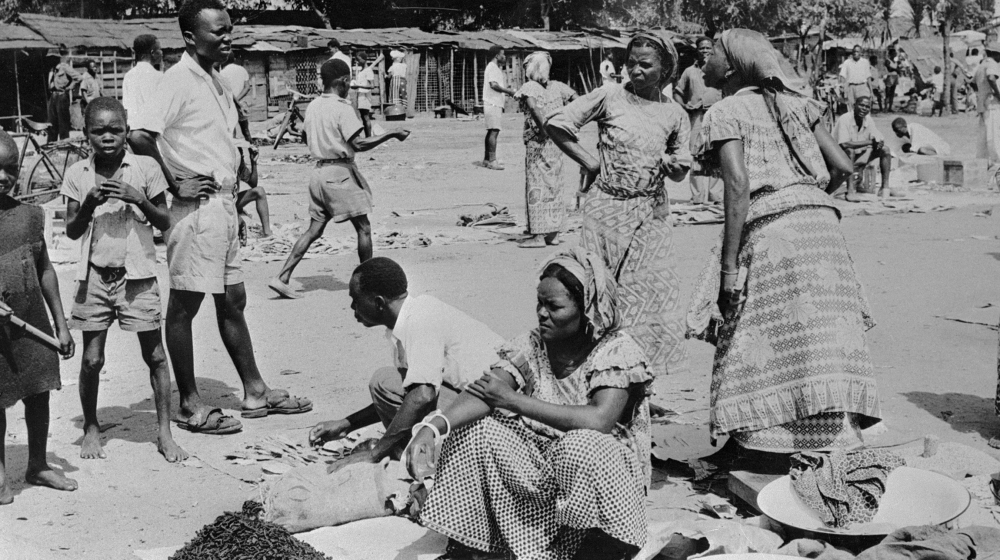

June 30 marks the 60th anniversary of the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s (DRC) independence from Belgium.

This year’s milestone comes some 15 months after the DRC experienced its first peaceful transfer of power in its turbulent post-colonial history.

The vast, mineral-rich country has long been exploited for its resources, including through the period of direct Belgian rule and under King Leopold II of Belgium, who held it as his personal dominion from 1885 to 1908.

Leopold’s exploitative reign is seen by many historians as one of the most brutal in the history of European colonialism, with millions of Congolese killed and maimed during his rule. Earlier this month, as protests against racism swept the world in the wake of the United States police killing of George Floyd, a 150-year-old statue of Leopold in Antwerp was removed after being targeted by activists.

To mark the DRC’s 60th independence anniversary, Al Jazeera spoke to Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, a prominent scholar on African politics and author of The Congo from Leopold to Kabila, to discuss the impact of colonial rule on DRC, recent political developments in the country and what might come next.

Al Jazeera: What has been the lasting effect of King Leopold II’s rule on the politics and people in the DRC?

Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja: King Leopold left us a very bad legacy – a lasting legacy of authoritarianism [and of] a predatory state that is there for itself and the people. Rulers think they control the country, that they can do anything they want to do and do not care about the people; that is the major problem affecting our country.

It happened with the Belgian colonial system after Leopold between 1908-1960, it happened with the regimes of Mobutu Sese Seko and his successors, Laurent Kabila and Joseph Kabila.

Today we are fighting to change that, to establish a rule of law so that rulers will know that they are supposed to be servants of the people rather than their masters. We still have this concept that rulers are masters who can do anything they want to do; who can embezzle government funds and destroy public property.

Al Jazeera: To what extent does the toppling of Leopold’s statue in Belgium serve any kind of justice for the people of DRC?

Nzongola-Ntalaja: It does absolutely nothing for the people of DRC. Maybe it does something for the Congolese who live in Belgium, since we have a large number of Congolese living there – that they don’t have to see the figure of this evil man on a daily basis.

In Belgium, there are statues of King Leopold all over the country; they consider him a magnificent king and hero while today we know him as a person who is a criminal, a person who does not deserve any honour whatsoever.

Al Jazeera: Should we still pinpoint blame on the Belgian colonial rulers for what is happening in the country’s politics today, or are there other national and regional factors that are also responsible?

Nzongola-Ntalaja: The blame starts with the so-called Congolese leaders. As Amilcar Cabral – one of our greatest African leaders – once said, we are first of all to examine our own weaknesses.

The Congolese leaders are the ones who followed into the footsteps of King Leopold in treating the state as their personal property and neglecting the people, the most important element in any country.

However, we should not only blame them. The international community shares that blame. Major powers, especially the United States, Belgium and France, have been involved in Congolese politics since independence. The United Nations, which has intervened in the Congo twice, has not really taken a good position in terms of resolving problems and sometimes play games with the lives of the people.

There is a lot of blame to go around, but certainly the most important people to blame are Congolese rulers.

Al Jazeera: Many people in the DRC have, as some might say, become “disillusioned” by Congolese politics, and there also seems to be tension between people and the politicians. Why is this?

Nzongola-Ntalaja: The government does nothing for them; all the government knows to do is to oppress them.

There were stories recently [after the government] decreed that people in Kinshasa have to wear masks [to stem the spread of coronavirus]. Sometimes the police would find people walking without a mask and shoot at them. What kind of nonsense is that? Why would you kill someone for forgetting or refusing to wear their mask?

So we still have a colonial mentality; this idea that the armed forces and the police are there to oppress the people rather than to protect them.

We have to change the mentality. We have to train soldiers to know that their job is the protection of the people, not to oppress the people. Police love to be on traffic duty, they stop people for no good reason to get bribes out of the drivers and so on. All of this is due to the fact that civil servants, police included, are very poorly paid.

Al Jazeera: Is there any glimmer of hope for the Congolese people to see in their country some form of legal and political order reinstated to serve them in the near future, or is there still a long way to go?

Nzongola-Ntalaja: Absolutely, there is great hope now. President Felix Tshisekedi is very popular among the people of Congo because they see him as the son of the historic leader of the democracy movement, Etienne Tshisekedi, whose motto was “The people before everything else”.

If Tshisekedi was to live up to the motto of his father and continued what he started to do since he came to office in 2019, there is hope. The main obstacle is the fact that [Joseph] Kabila and his cronies are still very powerful. As long as he continues to be powerful, Tshisekedi can’t move very far.

Al Jazeera: What hope do you hold for the DRC in the future?

Nzongola-Ntalaja: Our founding fathers in the 1960s Africa were extremely happy when Patrice Lumumba [won the first elections] to become prime minister. They were expecting that with Lumumba they can succeed in using the resources of the Congo for the development of the African continent as a whole.

We have basically everything, whether it’s in terms of mineral resources, forest resources, land, arable land for cultivation, rivers, lakes and so on. We can feed the whole of Africa and provide electricity to it.

So our vocation as a country is to play a major role in the development of the African continent. But unfortunately, 60 years have been wasted, [and] that is something most of us patriots and pan-Africanists feel ashamed of.

We would also like to see that we can rescue our state from these thieves and criminals who have been running it.

This interview has slightly been edited for brevity and clarity