Algeria steps up diplomacy in hopes of ending Libya’s war

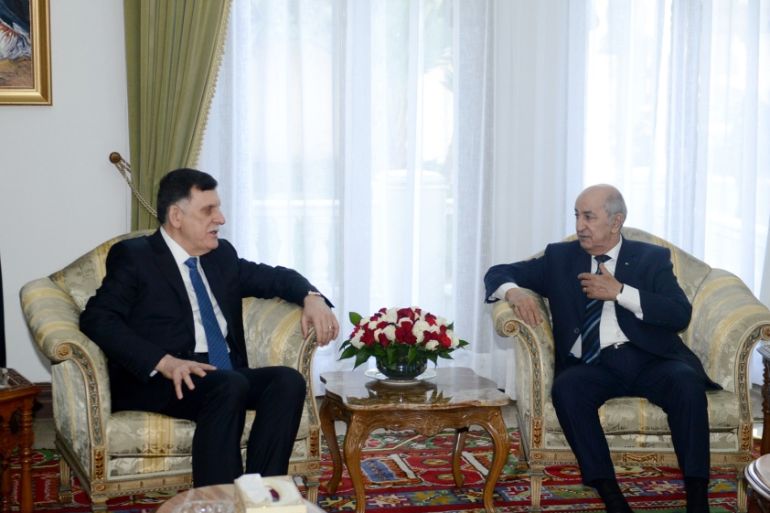

Algiers renews offer to mediate between warring sides in Libya as President Tebboune hosts PM al-Sarraj, Speaker Saleh.

Peace talks rarely produce the desired outcome when parties to a conflict believe they can still, through force, change the situation in their favour.

This was the harsh lesson Algeria learned when it proposed to host Libya’s warring sides in January, following what initially appeared to be two promising summits in Moscow and Berlin to de-escalate tensions.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsCIA chief visits Libya after Lockerbie suspect handover

Libya: Violence to Votes

In Libya, anger and uncertainty after polls delayed

In this case, it was renegade commander Khalifa Haftar’s decision to resume a nine-month-long offensive on the internationally recognised government in Tripoli that derailed Algiers’ attempt to resolve one of its most pressing national security threats.

Reluctant giant

A giant in the geographic and perhaps military sense, Algeria has been all too reluctant to assume the role of power-broker that some analysts say its position in the region confers upon it.

|

|

For years, the country – ruled by a coterie of generals and politicians whose hold on power dates back to the early days of independence from colonial France in the 1960s – did not make much noise about its preoccupation with the deteriorating security situation next door.

The impression that it would be content with making sure violence did not spill over into its own territory was reinforced by the serious stroke that Abdelaziz Bouteflika, its leader of some 20 years, suffered to in 2013, rendering him absent from the international political scene.

But there are signs the new administration of President Abdelmadjid Tebboune, who succeeded Bouteflika in December following months of protest over his controversial bid to seek reelection, is looking to shake things up – and most importantly, that developments on the ground this time may be conducive to a permanent settlement.

The move comes as Arab League foreign ministers hold an emergency meeting on Tuesday to seek a peaceful way forward in Libya.

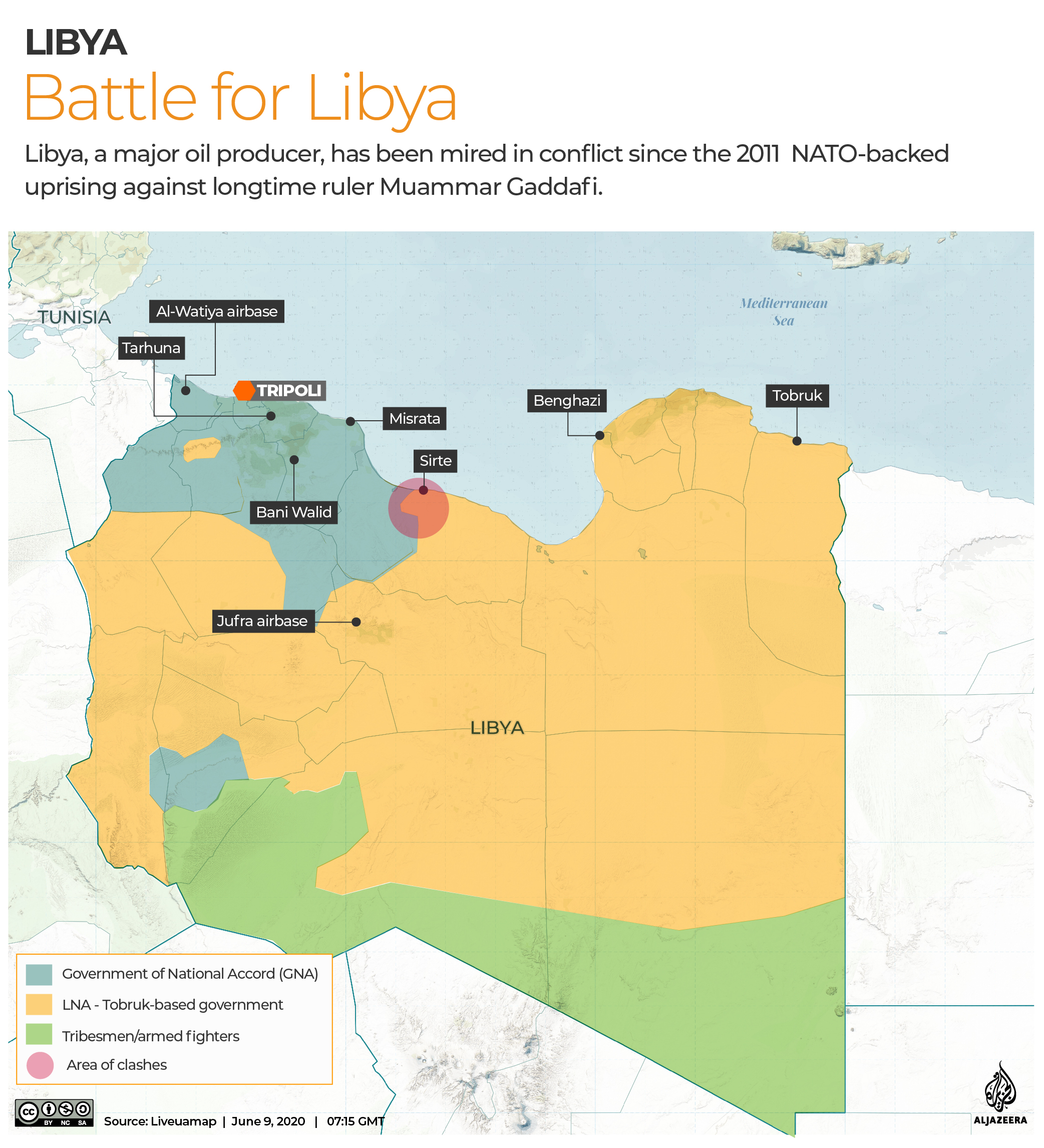

Amid a counteroffensive that has seen forces loyal to the UN-brokered Government of National Accord (GNA) retake much of western Libya, Tebboune reiterated his country’s readiness to mediate between the warring parties.

“With regards to the ebb and flow in Libya, our fundamental principle, which we’ve clearly outlined, is that the resolution of the conflict cannot be military,” Tebboune told a news conference earlier this month.

“World powers agree with our plan and its approach.”

Credible mediator

By the time Haftar launched his offensive in April 2019, Algiers was already bogged down in a months-long political crisis that even Bouteflika’s departure seemed unable to end.

And though the domestic crisis was a factor in Algeria’s slow reaction to the unfolding chaos in Libya, it was ultimately the investment of a multitude of foreign actors in Haftar’s campaign that proved to be the final blow to peace talks in the North African country, according to Cherif Dris, a political science professor at the Algiers School of Journalism.

“The involvement of several outside powers in the Libyan conflict had complicated Algeria’s ability to impose itself, which, to begin with, was already compromised by the absence of a head of state,” Dris said.

The intervention of the United Arab Emirates, Russia and Egypt on the side of Haftar and Turkey’s backing of the GNA have prolonged the conflict and thwarted the UN’s peace efforts.

Its strict military doctrine of non-intervention outside its borders and aversion to foreign presence in the region further complicated Algiers’ diplomatic efforts.

The limits of Algeria’s diplomacy-only approach was highlighted in January when Tebboune declared Tripoli a “red line that no one should cross”.

The call, which had come just weeks after Haftar announced an umpteenth “zero hour” to take over the city, hardly impacted local and foreign actors’ calculations as arms shipments continued to pour into the war-torn country in violation of a 2011 UN arms embargo.

Still, Algeria’s commitment to neutrality – while nominally recognising the GNA as Libya’s legitimate government – has been impressive.

|

|

Not even Haftar’s threat to wage war on it provoked a reaction, with senior officials maintaining cordial ties with eastern Libya and Foreign Minister Sabri Boukadoum visiting the Ajdabiya native Haftar, whom Algiers recognises as a key stakeholder, in his bastion city of Benghazi.

For Hasni Abidi, director of Geneva-based think-tank CERMAM, this makes Algiers a particularly attractive venue for the belligerents.

Tebboune’s hosting of both Aguila Saleh, speaker of the eastern-based House of Representatives and an ally of Haftar, and GNA Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj this past week was again demonstrative of the country’s willingness to remain equidistant from both.

In contrast, the GNA refused to attend an Arab League video conference called for by Egypt, whose recent offer to broker a ceasefire it rejected. On Saturday, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi said his military may intervene if Turkish-backed GNA forces continue to try and capture the strategic Libyan city of Sirte currently held by Haftar.

“Any Egyptian attempt at mediation will be criticised by political actors in the west because Cairo is seen as part of the problem and not a solution,” Abidi said.

Just as important in Abidi’s estimation, however, is the great lengths that Algiers has gone to to court not only Libya’s political leaders but also tribal and civil society actors from across the geographic and political spectrum.

“Algeria’s proposal does not date back to the Berlin conference. Its mediation efforts go back to 2014 when, under the UN’s auspices, Algiers hosted meetings that included notables and tribal chiefs to give popular legitimacy to any political agreement,” Abidi said.

This is because Algiers believes that diplomatic action alone will not suffice in ending the Libyan crisis, and an intra-Libyan dialogue is needed, according to Abidi.

The burden of securing the border

The global economic downturn caused by the coronavirus pandemic is another important factor that helps explain oil-rich Algeria’s eagerness to see an end to the conflict.

By the president’s own admission, securing the country’s border with Libya, which stretches along some 1,000km (600 miles) of arid, sparsely populated desert, is becoming increasingly costly.

“Algeria’s national interest is that there be peace at our border. If not, we’ve got to arm ourselves,” Tebboune explained.

Tebboune said there was no question about where his priorities lie and that between mobilising troops and investing in the economy, he would rather create jobs for the country’s youth.

According to the local El Watan newspaper, it costs Algeria about $500m a year to secure its border with Libya.

Though that sum constitutes a mere 5 percent of Algeria’s $10bn military budget, it would go a long way to making up for the shortfall in oil revenues, the country’s single most important source of income.

|

|