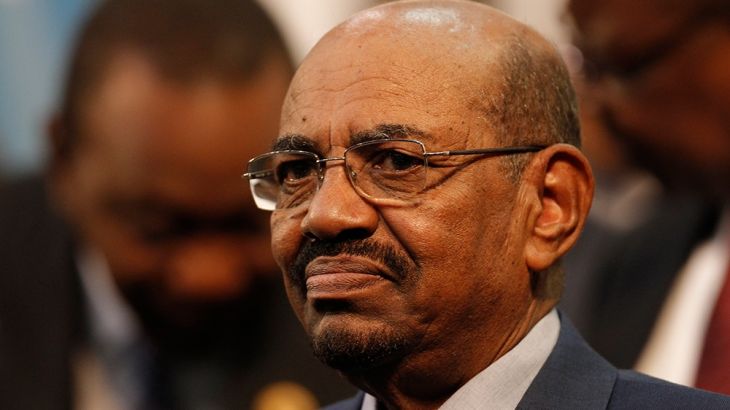

Profile: Omar al-Bashir, Sudan’s longtime ruler

Sudan’s military deposed the former president, who ruled the country for three decades, after months-long mass protests.

After 30 years, Omar al-Bashir‘s reign ended almost the same way it started.

Sudan’s longtime president seized power in a military coup on June 30, 1989, and stayed in office until April 11, 2019, when he was overthrown and arrested by the armed forces.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsOusted President al-Bashir in Sudan military hospital, army says

Sudan’s pro-democracy activists mark anniversary with protests

Sudan military leader urges troops to back democratic transition

Al-Bashir had been taken to “a safe place,” General Awad Ibn Auf said in an address to the nation on Thursday afternoon after declaring the “toppling of the regime”.

But al-Bashir’s downfall was brought about by thousands of ordinary Sudanese from all walks of life who took to the streets for four months to demand an end to the 75-year-old’s rule.

The demonstrations – organised by doctors, teachers and lawyers, among others – erupted over rising food prices before morphing into broader demands for political change, the culmination of years of anger over long-standing corruption and repression.

Dozens of people have been killed in protest-related violence since the start of the pro-democracy demonstrations.

Over the course of his time in office, al-Bashir led Sudan through several conflicts and became wanted by an international war crimes tribunal for alleged atrocities in Darfur. He was also the last man to lead a united Sudan, prior to South Sudan’s independence in 2011.

|

|

Rise to power

Al-Bashir was born into a peasant family in 1944, in Hosh Wad Banaqa, northern Sudan, which until independence in 1955 was part of the Kingdom of Egypt and Sudan. After finishing high school in the capital, Khartoum, he enrolled in a military academy in Egypt in 1960. In 1973, he was part of the Sudanese units that were sent to Egypt to fight in the Arab-Israeli war.

In 1975, he was appointed as the military attache in the United Arab Emirates. Upon returning to Sudan, he was appointed garrison commander and in 1981 he became the head of an armoured parachute brigade. In the mid-1980s, he had a central role in the armed forces’ campaign in the south of Sudan in the civil war against the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Army.

As a colonel in the Sudanese military, al-Bashir was well positioned to lead a bloodless military coup in 1989 against Sadiq al-Mahdi, the prime minister of a democratically elected government.

Al-Bashir was subsequently appointed chairman of the Revolutionary Command Centre for National Salvation (RCC), which was established as a “transitional” government.

Having allied with Hassan al-Turabi, the speaker of the Sudanese parliament and head of the National Islamic Front, al-Bashir dissolved parliament, banned political parties and went on to introduce Islamic law.

The mainly animist and Christian southern Sudan rejected the introduction of the new legal system, and the decades-long north-south civil war intensified.

Political conflict

In 1993, al-Bashir abolished the RCC and appointed himself president of Sudan, but retained military rule.

Three years later, Sudan held presidential and parliamentary elections, and al-Bashir, running completely unopposed for president, won with 75 percent of the vote. He would eventually legalise the registration of political parties in 1999.

Later that year, al-Bashir removed Turabi, who had grown increasingly close to Muslim political groups unpopular in the West, from his post as parliament speaker and had him imprisoned.

In 2000, al-Bashir was re-elected after winning 90 percent of a popular vote in an election described as a sham by the opposition.

A wanted man

Al-Bashir was the only serving head of state to be indicted for war crimes.

The leader and several senior ministers in his cabinet have been criticised for what the United Nations has called “ethnic cleansing” in the western province of Darfur, home to a number of non-Arab tribes who rebelled against the government in 2003.

The tribes of Darfur accused al-Bashir’s administration of siding with Arab tribes in a decades-old fight over scarce resources among the province’s communities.

The UN estimates that between 200,000 and 400,000 people have died in the conflict, with a further 2.7 million displaced. But al-Bashir’s government claimed that the UN, influenced by Western powers, had exaggerated the numbers.

In June 2008, the International Criminal Court (ICC) charged Bashir with war crimes and crimes against humanity in connection with the ongoing attacks against Darfur’s non-Arab ethnic groups. The ICC has since issued two arrest warrants against him.

Despite the arrest warrants, al-Bashir has visited several countries including Syria, Ethiopia, Libya, Qatar, Egypt and South Africa.

In 2010, al-Bashir was re-elected with roughly 68 percent of the vote. The opposition, however, alleged fraud and election observers said the polls did not meet international standards.

The following year, southern Sudanese citizens overwhelmingly backed splitting from the north in a referendum, which led to the creation of the world’s youngest country.

The 2011 secession of South Sudan deprived Sudan of the majority of its oil revenues and stoked spiralling inflation and widespread shortages.

As a result, opposition groups and ordinary citizens increasingly began expressing their anger with the inability of al-Bashir’s government to address their grievances, improve economic conditions and introduce political reforms.