UN urged to suspend Myanmar return plan for Chin amid unrest

Ethnic Chin people were told last year it was safe to return but experts say situation in Myanmar is too volatile.

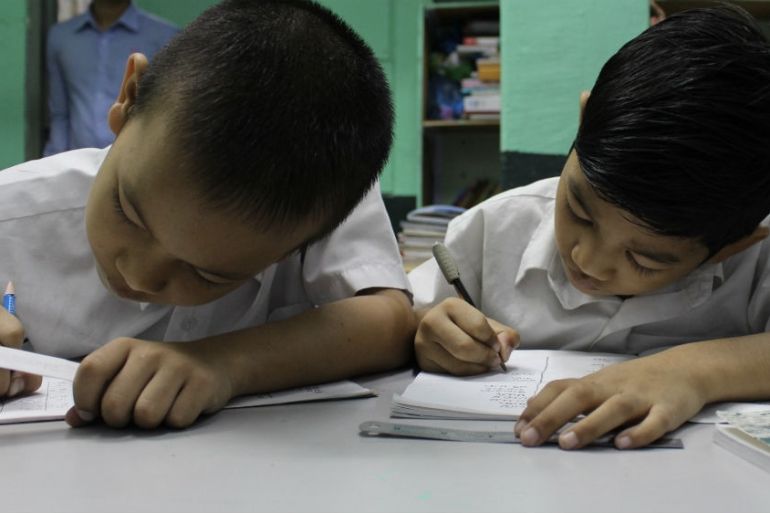

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia – Inside a Kuala Lumpur learning centre, a group of boys and girls is hunched over their notebooks, studiously copying the Burmese words their volunteer teacher has written on the board.

As children of ethnic Chin people who fled Myanmar years ago, most of them have grown accustomed to the insecurity of life as an asylum seeker or refugee.

But now, they are facing a new test – moving to a homeland they have never known.

“These children are born in Malaysia,” said headteacher Mang Pi, who fled Myanmar as a teenager in 2010 to escape being forced to work for the military. “Their documentation is not there and it won’t be easy for them to get citizenship. They will end up in limbo – not going back, not going forward.”

About 39,000 Chin people live in Malaysia, according to community groups. They are unable to work or send their children to school. They are also at risk of police detention because Malaysia is not a signatory to the United Nations‘ 1951 Convention on Refugees.

|

|

Recognition in the form of a card from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) provides some security and cheaper healthcare, but in May last year, the refugee agency told them that the situation in Myanmar’s Chin State was “stable and secure” and the community was no longer in need of its protection.

The decision, known as “cessation”, means the UNHCR believes it safe for Chin to start returning to their homeland.

Broadly, it gives Chin who are registered with the UN agency three options when their card expires: return to Myanmar; extend the card’s validity until the end of 2019 and lose refugee protection from 2020; or go through the refugee verification process to prove their status again. That option carries the risk of rejection and losing existing protection.

“Only those individuals UNHCR confirms are still in need of international protection will remain registered and benefit from international protection,” the agency told the community.

The move sparked protests by Chin refugees in Malaysia fearing for their safety amid continuing reports of violence in Myanmar’s western Rakhine State, on the southern border of Chin State.

“The UN has to review if they are really concerned about the lives of human beings and the rights of refugees,” James Bawi Thang Bik, the coordinator at the Alliance of Chin Refugees in Kuala Lumpur, told Al Jazeera.

‘Intimidating presence’

The largely Christian Chin are one of at least 135 ethnic groups in Myanmar and number no more than 1.5 million people. During decades of highly-centralised military rule, they struggled to assert their identity. Abused by the army and the target of political and religious discrimination, many fled the country.

Some went to India, others to Malaysia. In both countries, they found peace, if not security. The estimated 4,000 Chin in India are also facing cessation.

In 2017, the Myanmar military’s brutal military crackdown on the Rohingya in Rakhine, which sent hundreds of thousands of people into Bangladesh, triggered alarm among Chin refugees.

Now, outbreaks of violence between the armed forces and the Arakan Army, a rebel Buddhist group, are spilling over into Chin State, a rural, mountainous region that borders India.

“It was only in August 2017 you had an exodus of 700,000 Rohingya fleeing the country amid claims of genocide,” said Evan Jones, the Bangkok-based programme coordinator for Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network. “The fact remains that this is a government that cannot provide safety for its citizens. What’s the rush?”

![A church in Myanmar's Chin State - many Chin are Christian and say the government makes it difficult for them to practise their religion [File: Gemunu Amarasinghe/AP]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/8bfba043a0e0483dbb334d6d48a928fc_18.jpeg?quality=80)

Edith Mirante, who has worked on Chin issues since the 1980s and has visited the area a number of times, says the Arakan Army has used the southern part of the state as a training ground.

“They drew the Tatmadaw (the Myanmar army) in and that sent Chin people fleeing across the border in late 2017,” she told Al Jazeera. “The Tatmadaw presence is quite high throughout the state. Every town has a garrison of troops. It’s certainly a very intimidating presence for the Chin.”

The Chin Human Rights Organisation (CHRO), which monitors the situation on the ground, says there were at least four occasions in 2017 when people were forced into India as a result of fighting between the Arakan Army and the Myanmar military.

Salai Sang Hnin Lian, at CHRO’s office in the state capital of Hakha, says its monitors continue to report “recurrent” outbreaks of violence, particularly around Paletwa on the southern border. The government has also imposed measures that restrict Chin’s ability to practise their religion, he said.

“Chin State itself is not the way that it is claimed,” he told Al Jazeera, referring to the UNHCR’s decision.

‘Always responsive’

The cessation process began in August and is due to be completed by the end of December this year.

The UNHCR, however, says its decision is not set in stone.

“We understand the concerns,” UNHCR spokeswoman Caroline Gluck told Al Jazeera on the phone from Thailand’s capital, Bangkok.

“We are constantly reviewing [the situation]. We are cognisant of the fact that things can change, and can change very quickly.”

She stressed the agency was “always responsive” to changing conditions or new developments.

The UN’s own guidelines on cessation require “substantial and enduring changes” across a refugee’s country of origin, said Kirsten McConnachie, a University of East Anglia academic. The standard is set high because of the potential consequences.

“What’s unusual with this decision is that there isn’t that kind of substantial and enduring change,” McConnachie told Al Jazeera. “There are so many things going in in Myanmar that suggest that’s not the case.”

![A boy learning the Burmese language at a school run by ethnic Chin refugees in Malaysia [Kate Mayberry/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/7f4dff67b11f493481d18cfa03d965da_18.jpeg?quality=80)

‘Closing of files’

Figures in Malaysia show the number of Chin registered as refugees and asylum seekers has already dropped sharply. At the end of December, the UNHCR in Malaysia said it had 26,180 Chin refugees and asylum seekers on its books. Before the decision was announced, there were 31,150.

The agency told Al Jazeera the decline reflected the “routine closing of files”, including for those whose application for refugee status had been rejected or refugees who had not come forward to renew their cards or were uncontactable.

Chin also made up the “vast majority” of the 2,400 people who were resettled from Malaysia last year, it said.

Back at the learning centre, Mang Pi says enrolment has fallen slightly since last year because parents who no longer have refugee cards worry about letting their children out in case they are stopped by the police.

In the kitchen at the back, a vat of soup is bubbling on the stove and the cook is getting ready to fry a pile of chicken nuggets for the children’s lunch.

Some of the older students took part in the demonstrations against the cessation announcement.

“Everyone knows cessation is not fair,” Bawi said. “If they [the UNHCR] do not review, we will have more protests.”