Habbaniyah, Iraq: From celebrity haunt to safe haven among ruins

Once an elite holiday destination, then a refuge for those displaced by ISIL, the resort town is trying to rebuild.

Habbaniyah, Iraq – Hamed Salama Ali was just 21 years old in 1985 when he left his native Egypt and travelled to Iraq in search of opportunity.

The young man from Mansoura found work at the then newly-opened Al Habbaniyah Tourist Village – a luxury holiday destination by the blue waters of its eponymous lake.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsBoeing hit with 32 whistleblower claims, as dead worker’s case reviewed

US imposes new sanctions on Iran after attack on Israel

A flash flood and a quiet sale highlight India’s Sikkim’s hydro problems

Today, Ali, now 55 years old, is a first-hand witness to the waxing and waning fortunes of the resort where he is still a loyal employee.

In a featureless events hall that was once a five-star restaurant, he reminisced to Al Jazeera over tiny cups of sweet, black coffee.

“From 1981 until 1988, it was like the golden age of the resort,” he mused.

Some 90km (56 miles) west of Baghdad, in Anbar Province, Habbaniyah is an oasis in a desolate landscape.

Habbaniyah was designed to resemble a French seaside village, with colourful homes dotting the lakeshore.

When it opened its doors in 1981, it heralded the twilight of a decade of rapid development and financial prosperity in Iraq.

With 300 hotel rooms and 500 bungalows, Habbaniyah became a favoured vacation spot for local and international celebrities and politicians, including late former President Saddam Hussein and his family, whose exclusive white villa can still be seen perched on a secluded peninsula.

In the 1980s, guests were treated to local and international cuisine at long tables draped in white linen and lit by candlelight, while foreign bands played the night away.

Guests booked their New Year’s Eve rooms months in advance and celebrities such as Egyptian actress Soad Hosny and Iraqi singer Kadim Al Sahir were regular visitors.

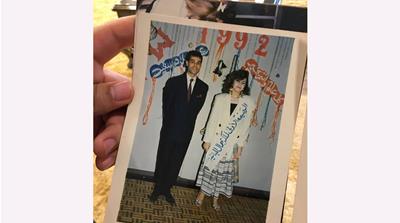

“All of the Iraqi singers who are now famous started off here,” Ali says proudly, looking through old pictures he keeps in a box. “Everyone who wanted to become a celebrity came here.”

Engagements, weddings and honeymoons were commonplace. Beauty competitions were held every weekend, with the winner receiving a complimentary week at the resort.

“We used to say the hotel was part of Europe,” said a sheikh from one of Anbar’s tribes who visited the resort with his family in the 1980s. “I saw men and women swimming together in swimsuits, and dancing. There was freedom.”

‘Good memories’

For a select handful of privileged Iraqi elites, the 1980s were a time of opulence and Habbaniyah resort was at the centre of it.

Even the eight-year Iran-Iraq war and Hussein’s austerity policies were unable to pierce the Habbaniyah bubble.

In 1989, a French organisation awarded the resort the Golden Hotel Trophy for best holiday establishment in the Middle East. The prize is still proudly displayed on the manager’s desk.

But Habbaniyah could not remain cloistered against powerful agendas and the hardships they would invite.

In 1990, Saddam Hussien ordered his military forces to invade neighbouring Kuwait, leading the United Nations to impose devastating sanctions on Iraq. Hyperinflation followed, along with widespread poverty and, for Habbaniyah, a drop in clientele.

Numbers continued to dwindle after the 1991 war, when Hussein, keen to bolster his pious credentials, banned Iraqis from drinking alcohol in public spaces and Muslims from selling it.

“This hugely affected tourism here in the resort,” says Ali, adding that he began to travel back to Egypt more often during those years as work in Iraq became scarce.

But some families continued to holiday at the resort despite the alcohol ban. “Habbaniyah always brings back good memories,” says 32-year-old Ahmed Zaki Alhaddad from Baghdad.

Every summer, between 1995 and 1999, Alhaddad’s parents and siblings piled into their 1986 Chevrolet Malibu and travelled westward to Habbaniyah.

“I still remember the smell of the water and the [bungalow] we used to stay in; I used to sleep early just to wake up early in the morning and go to the beach and play with the sand or swim.”

In 2003, after the United States invasion and the fall of Hussein’s regime, sanctions were lifted and some clients began to return. But the exclusivity that had once characterised the resort had vanished, as entry standards were relaxed to attract more visitors and boost revenues.

“From 2003 to 2013, we received a lot of people,” says Ali. “But the level of education and the level of class was different. We used to receive politicians and celebrities, but after 2003, anyone could come. It was sad for me.”

During this time, Habbaniyah also received American personnel from the nearby airbase. “They would book the disco space; I use to hear them party,” recalls Ali with a laugh. “They loved the shisha that I made.”

But the post-war tourist resurgence came to an end with the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) in 2014.

By 2015, the tourists were gone and Habbaniya was bursting at the seams with 24,000 displaced Iraqis.

What was once the height of hoteliery had become a safe haven for tens of thousands of desperate civilians.

After three years, the Iraqi government announced that the war against ISIL had been won. While most displaced people have since returned to their homes, more than 1,000 individuals still languish in tents just a stone’s throw away from the luxury hotel.

This year, Muayed Mshwaah was appointed manager and tasked with rehabilitating the resort. He began by enlisting the Ministry of Culture to prepare the area once again for holidaymakers.

“We cleaned, removed the trash and the rubble from the homes and beaches,” Mshwaah told Al Jazeera. “There was destruction everywhere.”

Remnants of the formerly displaced are still visible in the graffiti dotted around the resort as well as the cabins erected by the United Nations.

Mshwaah says around 40 percent of the area has been restored by the resort management and Habbaniyah’s municipal government, but there has been a major snag.

“Sixty percent was supposed to be reconstructed by a Turkish company, [and] unfortunately there’s been a delay,” he says.

The contract, said Mshwaah, was for $26m, but it is currently halted. “Originally, the Turkish company signed [the contract] in 2011 before ISIS,” he explained. “But because of ISIS and displacement, they couldn’t start.”

Hope for a better future

Despite the seemingly never-ending obstacles, Habbaniyah is still a vacation destination for Iraqis, drawing some 5,000 visitors every week, according to Mshwaah.

“It’s not about the money, it’s about people meeting here between different cultures and provinces and other religions,” he says.

But restoring the resort to its glory days is no easy task, and funding is key. Ony 120 bungalows have been restored, and the hotel remains in ruins.

According to the manager’s secretary, Anbari-born Speaker of Parliament Mohammed al-Halbousi has contributed to the resort’s reconstruction efforts. Habbaniyah pays for the rest by hosting events like Miss Anbar, seminars for non-governmental organisations and training sessions for universities.

“In two and a half years, the resort will be what it used to be if I stay in management,” said Mshwaah.

Meanwhile, employees who have invested decades of their lives into Habbaniyah are hopeful the resort can still recapture at least some of its former golden glory.

“I’m waiting,” says Ali. “I have been waiting [for things] to go back to normal, like they were in the 80s. The political issues since the 1990s have affected the work here directly. Our main job was entertainment night club, parties, weddings. But now that’s gone.”