Nigeria: Misery for students as university lecturers strike

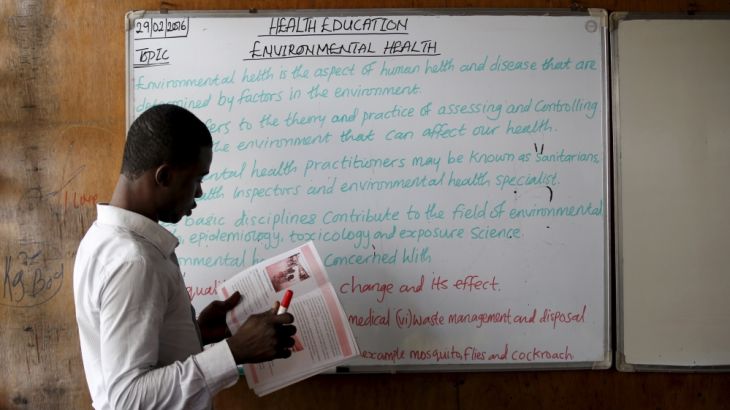

Students say they are facing a bleak future as labour deadlock between the government and professors continues.

Nsukka, Nigeria – On a hot December afternoon in this southeastern town, a dry, dusty wind blows over the main entrance gate of the University of Nigeria campus.

Only a few cars and a handful of people are trickling in and out. Six motorcycle taxi drivers are bantering, their bikes parked in upright positions nearby. There are few clients today.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsColumbia University leaders face scrutiny over anti-Semitism on campus

Top USC graduate cancelled over Gaza speaks out

Columbia president faces anti-Semitism Congress hearing: What’s at stake?

In an off-campus neighbourhood about 2km from the gate, third-year university student John Chukwu sits on his mattress in a single room in a rundown tenement. Reclining against the wall, he occasionally glances at sheets of paper on the bed as he makes notes. He is trying to solve ordinary differential equations.

But his room isn’t where he should be, at least not in the opening weeks of the semester.

“I honestly feel terrible,” Chukwu, a 25-year-old student of mathematics, said. “The strike by university lecturers is affecting me and other students because nothing is happening on campus.”

On November 4, the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU), the union of Nigerian university lecturers, announced it would be going on strike just a year after it suspended its last industrial action.

“This strike will be total, comprehensive and indefinite,” ASUU national president, Professor Biodun Ogunyemi, was quoted by local media as saying.

“Our members shall withdraw their services until the government fully implements all outstanding issues as contained in the memorandum of action of 2017 and concludes the renegotiation of the 2009 agreements.”

Public universities

|

|

With this declaration came the closure of more than 90 public universities in Nigeria. For nearly two decades now, the union and the central government have been at loggerheads over several issues including funding, salaries, university autonomy and academic freedom.

Though the government has continually entered into agreements with the union since 2001, university professors say implementation of the terms is slow and, in most cases, their requests are totally ignored.

Nigerian students bear the brunt of this long-standing battle between both parties, which fills parents and students alike with dread. At any time, it could mean anything between one week to five months of no education.

When Precious Mbah gained admission to study English and literature at the University of Nigeria in October, she was overjoyed. She travelled from the commercial city of Lagos on a 10-hour bus journey to Nsukka, a town in the southeastern Nigerian state of Enugu.

“I was excited and I look forward to seeing what the lecture hall will look like, what kind of classmates I will be meeting, what my lecturers will teach me and even how the campus environment looked,” Mbah said.

The next day she spruced herself up and walked to the Faculty of Arts complex. “My first day as a student began with the news that there was a strike by lecturers, and I was like what I have been hearing about has finally happened to me,” the 18-year-old freshman said.

Helplessness

Asked how her she feels about the situation, freshman student of music Linda Okwor struggled to rein in her emotions.

“I hate to say that my excitement reduced drastically when I found out that ASUU had gone on strike,” Okwor, 19, said. “I felt helpless and for the first time I hated this country.”

Anger and frustration among students can translate into outbursts of indignation towards university staff.

Okwor added: “Couldn’t ASUU have waited for us, freshmen students at least, to know what it actually feels like to be an undergraduate? Is this the ‘welcome’ they were supposed to tell us?”

But the chairman of ASUU branch at the University of Nigeria, Ifeanyichukwu Abada, told Al Jazeera that university employees also have children in public universities who are home because of the industrial action.

“If you look at the items ASUU is pushing for the government to implement they are of immense benefit to members of the public, not only to ASUU,” said Abada, also head of the University of Nigeria’s political science department.

“Strikes are not the best option but since we have irresponsible leaders who do not honour agreements it is the only language they understand.”

As long as the government continues to renege on its agreement with university teachers, strikes will continue to be a reality for Nigerian students, the union says.

Overcrowded and unhealthy

These disagreements forced the government to constitute an inter-ministerial committee to travel around the country to conduct an assessment of the issues raised by ASUU. In its report in November 2012, the committee found facilities for teaching and learning were, in its words “inadequate, dilapidated, overstretched or overcrowded” and in some cases improvised.

The report also revealed just 43 percent of Nigeria’s 37,504 university lecturers have PhDs. It noted that accommodation facilities for students were overcrowded and unhealthy.

“These conditions, coupled with the general condition of the universities, produce graduates that lack confidence and sometimes even self-worth,” the report noted.

The immediate impacts on students include a disruption of academic activities and a disjointed academic calendar. Once a strike is called off, students have to complete all coursework within a shortened timeframe, meaning they have less time to attend classes and study. Students who should ordinarily spend four to five years in the university sometimes end up staying an extra year or more because of the labour strife.

Government authorities have a penchant of threatening to sack lecturers who fail to return to work during industrial action. This often exacerbates tensions between academics and public officials.

Poor working conditions for academic staff have led to a brain drain since the 1980s. Some lecturers have been forced to moonlight as visiting professors in several universities at a time, making them less available.

The lack of trust in the university system has also fuelled growth in private institutions. At present, there are about 75 of them, mostly owned by churches, businessmen, politicians and wealthy individuals. But most are costly and out of reach for millions of Nigerians.

More students travel to neighbouring countries such as Ghana, Togo and Benin where they are sure to graduate within the timeframe required for their fields. Some even head to the United States or the United Kingdom.

In 2017, out of 37,735 African students studying in the US, 11,710 were Nigerian – representing 31 percent of the continent’s students there – the highest number from an African country.

Low pay

University staff have, as far back as 1973, demanded better wages.

University staff had enjoyed better salaries in the past. However, after the military entered and dominated the political space starting in 1966, things began to change. Military rulers meddled heavily in university affairs, lecturers left the country for better working conditions, causing learning and research to deteriorate.

ASUU was formed in 1978 when the brain drain was gaining as much steam as the struggle for university autonomy and academic freedom. In 1988, it organised its first strike, asking the government to address the issue and provide more funding. The military government proscribed the union and tortured and detained some of its leaders.

Though the ban on the ASUU was lifted in 1990, the repressive measures to rein in union members, perhaps, made some more strong-willed. From 1992 until 2013, ASUU has embarked on industrial action nearly every year. The longest strike lasted from July 1 to December 17, 2013.

That action was a result of the failure of the government to implement a 2009 agreement stating it would improve funding and conditions of service and promote greater university autonomy and academic freedom.

One of the major issues in the memorandum of understanding signed in 2013 with the federal government involved a yearly fund of $687.5m to be deposited into a special account at the central bank to develop public universities. This was meant to happen every year until the end of 2018.

The central government has not kept its promise since 2013.

In September, the federal government approved $62.5m to develop public universities, falling short of the 2013 agreement.

Math student John Chukwu worries the seeming inability of the government to reach an agreement with ASUU could dismantle the new semester.

“I made plans on how to go about my lectures, personal study and recess hours,” he said. “But as it stands now, all of that has got to change owing to the strike.”