Brazil elections 2018: What you need to know

About 147 million voters head to the polls amid spiralling polarisation and converging crises.

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil – About 147 million Brazilians are heading to polls on Sunday in highly polarised presidential and congressional elections.

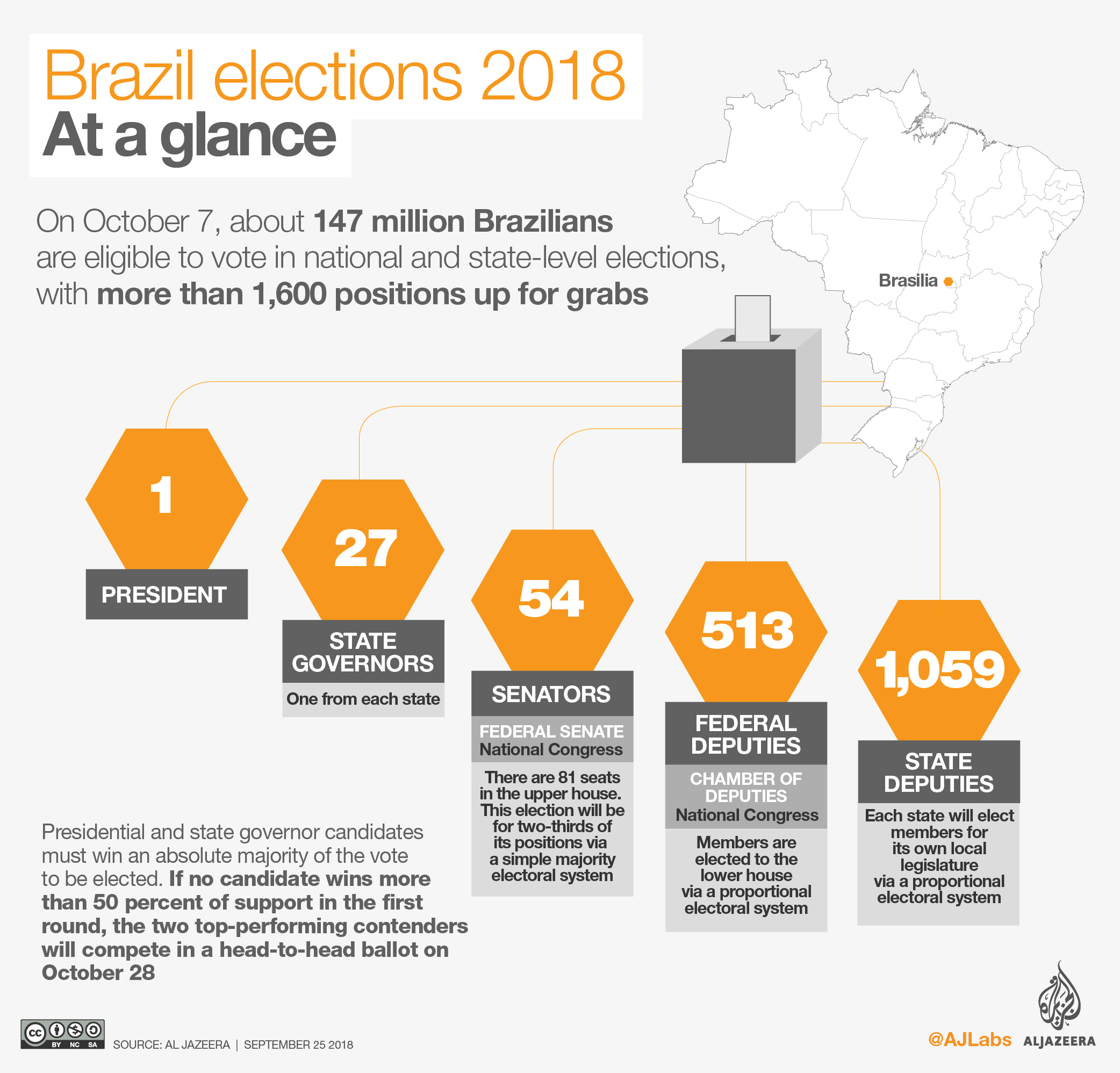

At stake, is the presidency and more than 1,650 national and state level positions.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsSolomon Islands prepares for ‘most important election since independence’

Six takeaways from first day of Trump’s New York hush money criminal trial

Manipur’s BJP CM inflamed conflict: Assam Rifles report on India violence

The vote takes place against a backdrop of widespread dissatisfaction prompted by a stuttering economy, worsening violent crime rates and several recent high-profile corruption scandals.

Here’s what you need to know about Sunday’s election:

Why does the vote matter?

Brazil, Latin America’s most populous country and largest economy, is a regional powerhouse.

Home to about 210 million people, Brazil forms part of the five-member “BRICS” group of major emerging economies alongside Russia, India, China and South Africa.

But several recent domestic setbacks have begun to erode the country’s standing on the world stage, according to Oliver Stuenkel, a professor of international relations at the Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV).

“Brazil at this point, and over the last few years, has lost its voice on international issues,” Stuenkel said.

“It is no longer able to project itself as a model … its legitimacy is lower today than four years ago [at the last election],” he added.

This year’s vote arrives at a critical juncture for Brazil’s future prospects as it battles to confront several complex and threatening challenges that have increased unrest and widened polarisation among the country’s citizens.

What are the key issues?

At the top of voters’ minds are Brazil’s economic, political and social crises.

From 2000 to 2012, Brazil seized on a global commodities boom to become one of the fastest-growing major economies in the world. A more than two-year deep recession, which began in mid-2014, has since rocked the country and stagnated growth.

Though technically out of the recession since last year, the economy is still struggling to recover and unemployment stands at above 12 percent, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics.

The fiscal downturn has coincided with numerous high-level corruption scandals since 2014 as part of the Lava Jato, or Car Wash, anti-graft probe and other interlocking investigations.

Widely popular former president Luiz Inacio ‘Lula’ da Silva was among more than 150 Brazilian business leaders, corporations and politicians convicted on the back of the investigations. He is now serving 12 years in jail and was barred from running in this election. Lula has consistently denied the charges, alleging they are politically motivated.

The scandals involving the former president and others have decimated public faith in the country’s political class and democratic institutions.

Just 17 percent of Brazilians have confidence in the national government, according to US-based consultancy Gallup, down from 51 percent a decade ago.

Violent crime, meanwhile, has surged in the last few years. In 2017, a record 63,880 homicides took place in Brazil, up 2.9 percent from 2016.

In the grip of a worsening public security crisis, Brazil is now home to seven of the world’s 20 most violent cities.

The combination of these factors has placed Brazil “on the front lines of the global recession in democracies”, Brian Winter, vice president of policy at the Americas Society and Council of the Americas and editor-in-chief of Americas Quarterly, told Al Jazeera.

“The issues present in Brazil are seen in a lot of places; disenchantment with the establishment, problems generating new employment, existential doubts over trade and rising violence,” Winter said.

“But in many of those cases they are just worse in Brazil than they have been in a lot of other places,” he added.

Who is being elected?

Voters will choose the country’s 38th president and all 27 of Brazil’s state governors.

Also up for grabs are most of the seats in Congress – including two-thirds of the 81-member upper-house Senate and all 513 places in the lower-house Chamber of Deputies – and 1,059 positions within state legislatures.

Who are the top presidential contenders?

Far-right frontrunner and controversial firebrand Jair Bolsonaro of the Social Liberal Party has led opinion polls in the run-up to the vote and is projected to win up to 35 percent of the vote, according to Datafolha polling institute.

A Rio de Janeiro congressman since 1991, Bolsonaro has styled himself as a political outsider untarnished by corruption and pledged to end Brazil’s security problems by militarising the police and loosening gun laws.

His numerous discriminatory comments on race, gender and sexual orientation as well as several highly controversial remarks about the country’s former military dictatorship – in power from 1964 to 1985 – have angered and alarmed tens of millions of Brazilians.

On Saturday, hundreds of thousands of Brazilians turned out in cities nationwide to protest his candidacy as part of a women-led #EleNao (#NotHim) movement. The next day, thousands of Bolsonaro’s supporters rallied throughout Brazil in response.

Last month, Bolsonaro was stabbed while out canvassing support in the city of Juiz de Fora, in southeastern Minas Gerais state, and has been unable to return to the campaign trail since.

![People holding national flags gather in front of the condominium where leading presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro resides to show their support, in Rio de Janeiro [Leo Correa/AP Photo]](/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/fe4261a61c4048148fb0168befb0ba5a_18.jpeg)

Fernando Haddad, Bolsonaro’s closest opponent and the leftist Workers’ Party (PT) replacement candidate for Lula, is trailing the former army captain in second place with about 22 percent of support.

Haddad, a former mayor of Sao Paulo and minister of education under Lula, has promised to “make Brazil happy again” and restore the economy to its former state of health under Lula’s presidency from 2003 to 2010.

He is facing the difficult balancing act of translating Lula’s widespread popularity among Brazil’s working class into votes for himself while also appealing to parts of the electorate with whom the former president and the wider PT are deeply unpopular.

Hostility towards the PT among some is high as a result of corruption scandals and the economic downturn which coincided with Dilma Rousseff’s, Lula’s successor, time in office from 2011 until her impeachment and removal from the presidency in August 2016.

Neither Bolsonaro nor Haddad appear likely to secure the absolute majority of support required to win office in the first round vote, on October 7, and are widely tipped to contest a second round head-to-head vote on October 28 instead.

Polling suggests Ciro Gomes, Geraldo Alckmin and Marina Silva – a trio of centrists who have all run for the presidency at least once before – will not catch up with the two frontrunners.

“In terms of the final two candidates it has actually been quite predictable,” Winter said.

“Where it does become unpredictable is in this runoff, if it does confirm that we are looking at Bolsonaro versus Haddad, then that’s about as close to a toss-up as you get,” he added.

However, Haddad and Bolsonaro both have high rejection rates, hovering at 40 percent for the former and 45 percent for the latter.

That could pose problems for Brazil post-election if, as appears likely to be the case, either of the pair is elected to the country’s highest office, according to Winter.

“If it’s one of these two candidates [Haddad or Bolsonaro] as president, I think they are going to face extremely difficult challenges on the economic and social front and possible questions about legitimacy,” Winter said.

“I think Brazil could come out of the election with a very divided society that may not be focused on the right things and may be focused more on division and this war between competing cults of personality than the very real economic, social and security challenges,” he added.

How does voting work?

More than 147 million people are eligible to vote. Participation is compulsory for “literate” Brazilians aged 18 to 70.

Participants will make their choices via an electronic voting system, using a single, number-based method. First, they will vote on state legislators, then congressional positions, state governors and, finally, the presidency.

The presidency, state governors and senators are decided on by a majority voting system.

Seats in the Chamber of Deputies and state legislatures, meanwhile, are determined using a proportional system.

Although most results will be decided on October 7, there may be a series of second-round runoff ballots held on October 28.

Presidential and state governor candidates, unlike senators, require an absolute majority vote to be elected.

If no such result is returned on October 7, the best two performers from the first round go head-to-head in a second poll three weeks later.

At every level of government, those elected face a huge challenge to overturn the current malaise weighing on Brazil, according to Stuenkel.

“The broad sense of crises is clearly present, there is a notion that things are difficult … there is a sense of crises and that there is a complexity to the crises,” he said.

“Brazil is in a very difficult situation.”