What is the West’s end game in Syria?

Were US-led strikes on Syria aimed at destroying chemical weapons, or an attempt to maintain geopolitical status quo?

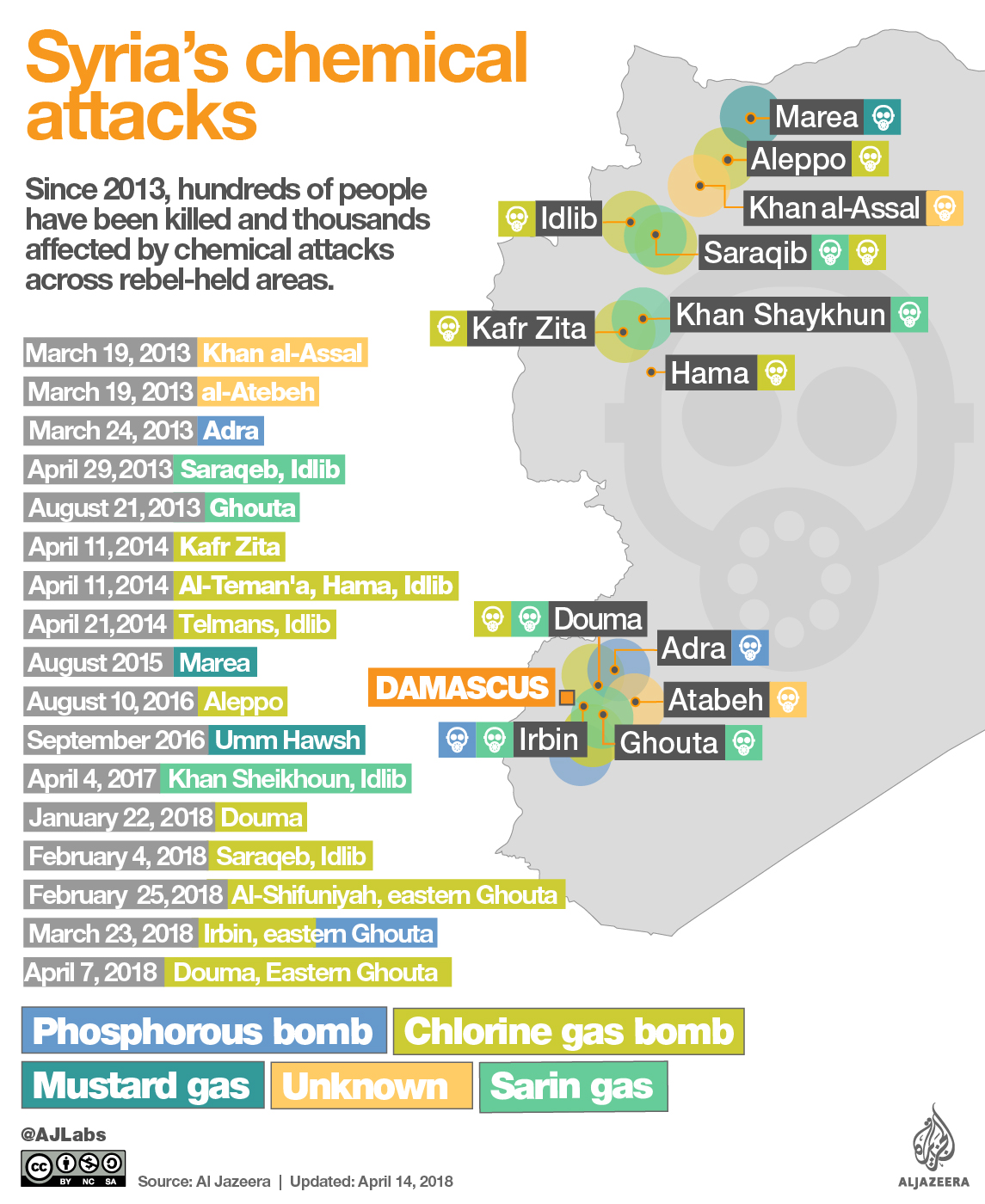

More than half a million Syrians have been killed over the course of Syria’s ongoing war, according to the United Nations, but only a fraction of those deaths happened as a result of 34 confirmed chemical attacks allegedly launched by Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in his war against armed opposition groups in the country.

With the disparity in the number of deaths attributed to the use of conventional weapons and chemical ones, civilians, who have lived through assaults of both kinds, wonder why chemical attacks constitute a “red line” to the United States and its western allies, while “barrel bombs and live artillery” do not.

The latest alleged chemical attack that hit Douma, a town in the former rebel-held city of Eastern Ghouta, was met with “triple assaults” by the US, France and the UK, through coordinated strikes on three presumed chemical facilities.

Shortly after, the US warned it “is locked and loaded” to strike Syria again if more chemical attacks occur.

But Syrians doubt the motives behind the response, despite the military action and threats imposed by the US.

Strikes should have happened ‘long ago’

Activist Hazem al-Shamy, who now resides in the town of Qalaat al-Madiq in Hama province, said the strikes were met with a “negative reaction” from locals.

“These strikes were ineffective and did not destroy any of the army bases from where fighter jets took off to launch barrel bombs on civilians in Eastern Ghouta,” he told Al Jazeera.

“There were several chemical attacks on various rebel-held towns since the war began, but we haven’t once seen a reaction from the international community that really harmed the Assad regime,” he said.

The western response came days after a bloody two-month offensive ended in Eastern Ghouta, launched by Assad and his main military ally – Russia, resulting in the destruction of yet another city that was once controlled by opposition groups.

With Russian military assistance, the relentless offensive killed at least 1,600 civilians and displaced more than 130,000 people from the Damascus suburb that had been under rebel control since mid-2013.

Nour Adam, who left for Syria’s north with his family as part of a series of evacuation deals made by Russia and opposition groups in Eastern Ghouta, believes that the US-led strikes “did not affect” the Syrian government.

|

|

“The strikes should have happened a long time ago. We were hoping they would hurt several regime bases as well as Iranian and Russian targets,” he told Al Jazeera from the outskirts of Hama.

Ordered by US President Donald Trump, the attacks targeted a research facility in Damascus, a weapons storage centre, a storage facility and a Command post in Homs.

“They waited for the regime to take Ghouta…It was all planned – the timing of the attack coincided with the retaking of the city by Russia and Assad regime,” Adam added.

Syria’s war, now in its eighth year, has seen the opposition make gains up until Russia entered the war in support of Assad in 2015. Since, Russia and Iran’s support helped tilt the balance of power in favour of Assad’s government.

In less than three years, the Syrian government has regained control of the majority of Syria, with opposition groups now restricted to the northern part of the country.

In the past, analysts have noted that the use of chemical weapons were aimed to pressure opposition groups into ceding large swaths of land.

Firas al-Abdullah, a local journalist who is now in Aleppo, believes the US would have “stopped” Assad years ago, if it were in their interest.

“If they cared about the Syrian regime’s violations, they [the west] would have responded a long time ago, they would have had Assad removed in a matter of five minutes,” he told Al Jazeera.

Though some were declared as thwarted by the Syrian forces, missile attacks were not about “regime change”, UK Prime Minister Theresa May noted.

They were to deter the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian government, as also noted by French President Emmanuel Macron.

“They don’t want to see the conflict come to an end,” al-Abdullah said.

“Any number of strikes that does not do away with the criminal regime is not enough, which is why these strikes have made no gains for the Syrian people, they were launched so that these nations can simply save face.”

‘Purely political’ move

Regardless of the large-scale response, which for the first time drew several countries to coordinate a wave of attacks, experts note that the action may have been “purely political” and had “a lot to do with the policy that was set during the Obama administration”.

Samer Abboud, an associate professor of international studies at Arcadia University, perceives the attacks to have been about containing the military and political discussion about the conflict.

“The attacks represent nothing new in American policy and it is apparent in how limited the strikes were,” he told Al Jazeera.

|

|

“The end game was to define the borders of the conflict and that border was the use of chemical weapons.”

Chemical assaults continued even after a Russian-brokered agreement to force Syria to give up its chemical weapons arsenal came into force in 2013, under former US President Barack Obama’s reign.

It is why Abboud believes the “stepped up” response will not deter the Syrian government from using chemical weapons as part of its conduct of war.

“Obama’s red lines didn’t scare them, the signing up to the agreement with Russia and the US in 2013 didn’t stop them,” Abboud noted.

Meanwhile, others believe the attack has “little to do with Syria”, and more to do with years of diplomatic efforts.

According to Aron Lund, a Syria expert and Century Foundation fellow, the US has never committed itself to “policing the Syrian conflict”.

“Obama didn’t do that, Trump hasn’t done it either,” Lund told Al Jazeera.

“Chemical weapons is a different kettle of fish. These weapons are internationally proscribed,” he said, noting that the US is in the process of destroying its own gas stockpile after acceding to the Chemical Weapons Convention in 1997.

“If gas warfare begins creeping back into conflicts across the globe, it would be destabilising in many ways and would undo decades of diplomatic labour on banning chemical weapons,” he said.

Economic sanctions imposed on Syria in 2015 highlight that “there is a red line”, and it is being enforced in different ways.

While some experts noted that the attacks were in fact launched to destroy stockpiles of chemical weapons, others believe they were an attempt to maintain the geopolitical status quo amid Syria’s proxy war.

“Behind every military attack there is a political motive,” Omar Kouch, a Syrian political analyst based in Turkey, told Al Jazeera.

“No matter how aggressive a military response is, it won’t lead to the fall of the Assad regime,” Kouch said.

“Any military action, especially with the absence of a US strategy on Syria, is only meant to force the government back into the Geneva political track,” he explained.

“They also do not want to see Putin’s government use chemical weapons whenever they please in Syria, and in the UK,” he said, referencing the Sergei Skripal case.

Collectively, analysts Al Jazeera spoke to do not believe that this, and any other potential future attack launched against Syria by the west, would alter the Assad government’s methods in combat.

And if the government does end its use of chemical weapons, they will continue to use “more barrel bombs”.