Where is al-Qaeda in Syria?

Despite Russia and the Syrian-regime saying they’re fighting al-Qaeda in Syria, the group’s presence has been shrinking.

In late December 2017, General Valery Gerasimov, head of Russia’s General Staff, told the Russian daily Komsomolskaya Pravda that the “destruction of Jabhat al-Nusra fighters” was a priority task in Syria for 2018.

About a week later, Syrian regime forces, with Russian and Iranian support, launched an offensive on rebel-held Idlib province. Syrian state media claimed they were fighting al-Qaeda.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsBurkina Faso army strikes killed dozens of civilians, says HRW

Somalia begins ‘efforts to rescue’ UN helicopter crew held by al-Shabab

Al-Shabab captures UN helicopter in central Somalia

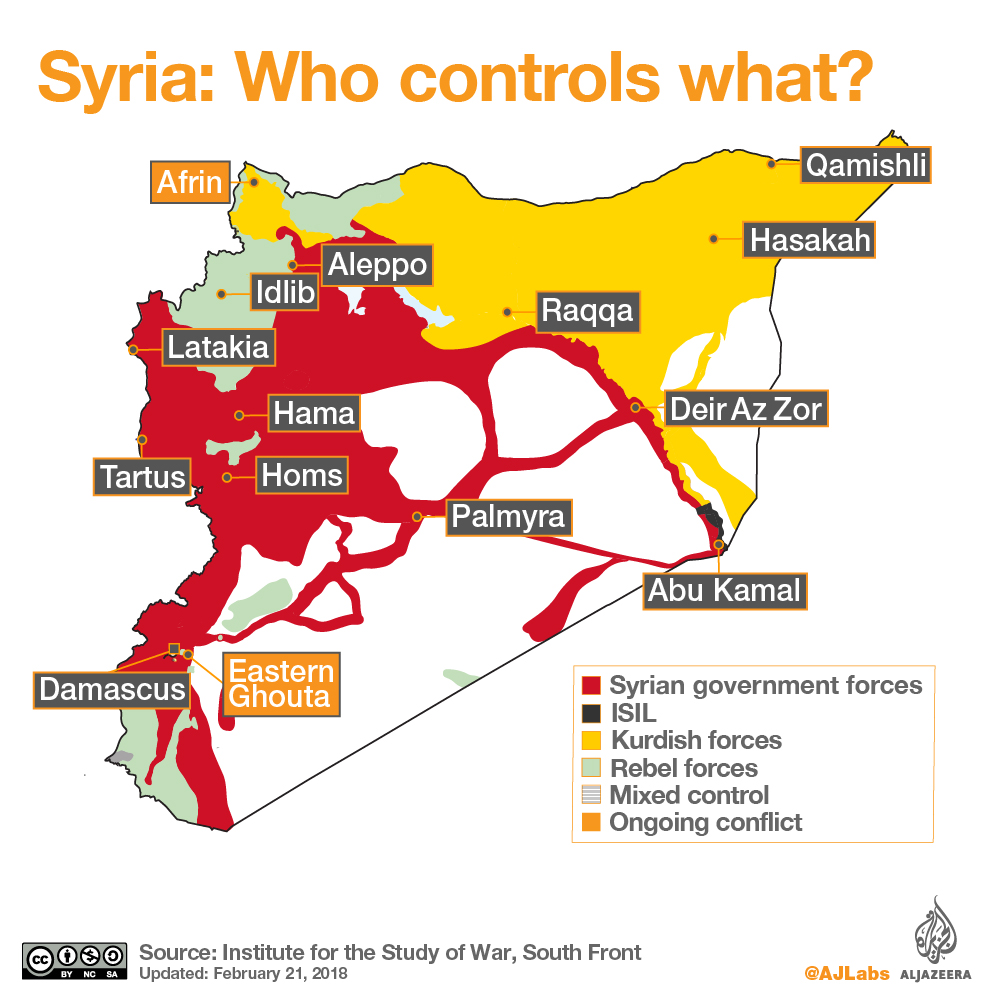

A month later, the Syrian regime escalated its bombardment of the rebel-held Eastern Ghouta enclave, near the capital, Damascus. As civilian casualties exceeded 500 in just a week and aid agencies warned of a humanitarian disaster, Syria and Russia maintained the bombardment was targeting Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (or al-Nusra Front, formerly affiliated with al-Qaeda).

“Jabhat al-Nusra fighters are not stopping their provocations. In Eastern Ghouta, they are bombarding residential neighbourhoods of Damascus, including the Russian embassy and trade mission,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said on February 19 during a conference in Moscow.

|

|

Russia and the Syrian government have often evoked the threat of Jabhat Fateh al-Sham or al-Qaeda to justify military operations that have violated de-escalation agreements over the past year.

But according to analysts, al-Qaeda’s ideological successor, Jabhat al-Nusra, and the group it formed in January 2017 called Hay’et Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) have a small presence in Eastern Ghouta and declining influence in Idlib, northern Hama, and western Aleppo provinces.

Internal conflicts following its split from al-Qaeda and defections have additionally weakened the armed group.

Small HTS presence in Eastern Ghouta

Jabhat al-Nusra was founded in January 2012 and gradually gained strength and followers in areas controlled by Syrian opposition armed groups. Unlike other areas in Syria, in Eastern Ghouta, the group’s presence has been largely limited by other, much larger groups.

According to Ahmed Abazeid, an Istanbul-based Syrian researcher, at its peak Jabhat al-Nusra had no more than 1,000 fighters in Eastern Ghouta. Defections, clashes with other armed groups and arrests have reduced the number to about 250 men.

In April 2017, Jaish al-Islam (the Army of Islam), one of the main Islamist armed factions in Eastern Ghouta, attacked the HTS and expelled it from the territories under its control.

The HTS had sided with Failaq al-Rahman (the Rahman Legion), another major Islamist armed group in the enclave, during clashes with Jaish al-Islam. This resulted in the two groups, which together have about 15,000 fighters, splitting control of Eastern Ghouta. HTS was also sidelined, Abazeid said.

“The majority of areas which the Russians are now bombing or are trying to advance in – especially those under the control of Jaish al-Islam – don’t have any fighters of Jabhat al-Nusra,” he added.

Even Failaq al-Rahman has sought to isolate HTS fighters. In late February, a group of armed factions, including Failaq al-Rahman and Jaish al-Islam, sent a letter to the UN declaring their readiness to “evacuate” the remaining HTS fighters from Eastern Ghouta within 15 days.

The spokesperson of Failaq al-Rahman, Wael Olwan, told Al Jazeera that in November 2017 the group had informed Russia that they are ready to evacuate HTS to Idlib province. According to him, the Russians did not let the evacuation happen.

On February 28, Lavrov – responding to a question from the media on the sidelines of a UN Human Rights Council session – said that Russia “will not object” to the removal of HTS fighters and their families from Eastern Ghouta.

“[The current resolution] says unambiguously that the ceasefire regime will not apply to the terrorists. If our colleagues at the UN and those who have influence with Jabhat al-Nusra coordinate this evacuation, we will not object,” he said.

HTS, as well as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also known as ISIS), has been left out of the February 24 UN ceasefire resolution on Eastern Ghouta and similar de-escalation initiatives in the past. Jaish al-Islam and Failaq al-Rahman have not.

Jaish al-Islam was also designated “moderate opposition” in a December 2016 list released by the Russian defence ministry and participated in the Russian-backed Astana talks. Representative of Failaq al-Rahman have also attended peace talks in Geneva.

Anti-HTS offensive in northern Syria

Jabhat al-Nusra was part of the loose alliance of armed factions that took over Idlib city and the province in the spring of 2015. Its influence over the province steadily grew at the expense of other factions and despite frequent civilian protests against their oppressive presence and human rights violations.

In July 2016, Jabhat al-Nusra announced its split from al-Qaeda in Syria and changed its name to Fateh al-Sham. The move came three years after a large number of its fighters broke off from its ranks to join what came to be known as ISIL, which also rejected al-Qaeda’s authority.

“That [move] back then was dismissed as a publicity stunt. If you look at the details, you realise that this was more than just a PR move,” said Heiko Wimmen, a project director at the Brussels-based research organisation International Crisis Group.

According to him, since the summer of 2016, the armed group has sought to reinvent itself as a nationalist armed group movement, giving less priority to international movement.

“This doesn’t mean that they have become nicer people. It means [different] tactics, ideology and leadership,” said Wimmen.

In mid-January 2017, what was still called Jabhat Fateh al-Sham attacked positions of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and a number of other smaller armed groups in Idlib province, entering a standoff with Ahrar al-Sham, one of the largest Islamist factions in the region, which was also included on Moscow’s “moderate opposition” list.

As a result of the tensions, smaller factions sought protection from Ahrar al-Sham, while others joined Fatah al-Sham, which changed its name to Hay’et Tahrir al-Sham.

In July 2017, tensions between the two large armed groups escalated again, and HTS attacked Ahrar al-Sham and its allies, which withdrew after week-long clashes allowing their adversary to dominate Idlib province.

In November 2017, the HTS formed the Syrian Salvation Government, which in December issued an ultimatum to the Syrian Interim Government of the Turkey-based Syrian opposition to cease all operations in the province.

In early January, Syrian regime forces with the help of Iran-backed militias and Russian air support, launched an offensive in southern Idlib province, causing tens of thousands of civilians to flee.

In response, FSA-affiliated groups and Ahrar al-Sham, Nour al-Din al-Zinki (previously associated with the HTS) and others created two separate operation rooms to counter the regime advances.

In mid-January, Abu Mohammed al-Joulani, the leader of the HTS, called for unity among armed factions in Idlib, but instead of heeding his call, other armed groups accused the HTS of withdrawing from areas in southern Idlib province to the benefit of the regime.

A month later, an alliance of Ahrar al-Sham, Nour al-Din al-Zinki and Soqour al-Sham attacked HTS. The factions managed to take over large areas in southern Idlib province, northern Hama province and western Aleppo province.

Earlier this week, Syrian opposition media reported that HTS sent reinforcements to Idlib city, its main stronghold, and Bab al-Hawa crossing on the border with Turkey.

HTS fighters managed to repel an attack on the crossing and counter-attack at other locations in Idlib. Bab al-Hawa serves as a major source of income for the armed group, which imposes a levy on goods that pass through it.

According to Wimmen, the attack on HTS was expected.

“The way [the HTS] basked in their victory, they were getting a lot of people ready to line up against them once the was right, with the external threat removed,” he said.

The deployment of Turkish troops in Idlib province stopped the regime offensive and gave a chance to HTS’ adversaries to attack it, he added.

“[The operation] has been quite successful. After it, you can no longer say that Idlib is under exclusive HTS control,” Wimmen said.

Before the attack, HTS had already been weakened by internal clashes, defections and killings. In late 2017, more than 35 high-profile foreign members of the HTS were assassinated, some of them al-Qaeda loyalists who were displeased with the formal split of the group.

According to Wimmen, some of the internal instability within HTS was the result of Turkish involvement.

“Turkey has tried to drive wedges into HTS because they see it as very problematic, and in particular the foreign element in it,” said Wimmen. “They are hoping to split it and hoping to arrive at a point where the real hardliners, who are mostly foreigners, and who you cannot make any deals with, form only a small faction that you can destroy without too much damage and cost.”

According to him, Turkey is likely to retain influence over Idlib and is, therefore, seeking to steer hardline armed groups into local governance. The Turkish presence in Syria’s north is also likely to stave off future plans by the Syrian regime to recapture the area, Wimmen said.