US Natives organise to end homelessness and racism

Unsheltered indigenous people face institutionalised challenges in their fight for equality across the US.

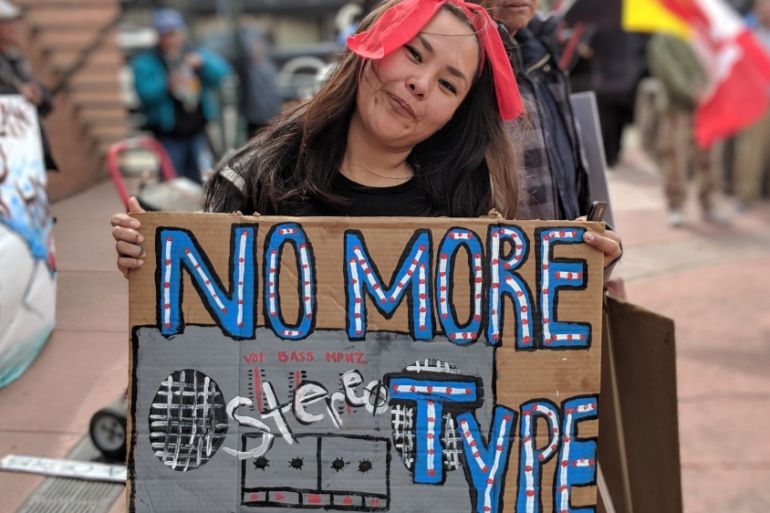

Dozens of homeless Native Americans and activists marched through the streets of Flagstaff, Arizona this week to call for an end to racist policing impacting their community.

Flagstaff is a quaint university city of about 70,000 people located among the historic landmarks of the US’ Route 66 highway, and close to the border of the Navajo Nation, a semi-autonomous Native American territory.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIndigenous people in Philippines’s north ‘ready to fight’ as tensions rise

Curfew announced for under-18s in Australia’s Alice Springs after unrest

‘We exist’: A Himayalan hamlet, forgotten by Indian democracy

The march ended in Heritage Square in the heart of Flagstaff’s historic downtown, where many of the city’s unsheltered population – and tourists – are found both in the warm summers and frigid winters.

Protesters called for a “homeless bill of rights”, culturally based shelters, and rehabilitation centres funded by the Navajo Nation and other indigenous groups, as well as an end to police discrimination.

“Before 1492, no one was homeless on this land,” Shane R, who declined to give his last name out of fear of reprisals, said in a statement to Al Jazeera.

More than 500 years after the arrival of Christopher Colombus and European colonialism in the Americas, indigenous peoples continue to suffer the repercussions.

At least eight unsheltered people died in Flagstaff in 2017 – some from exposure, some from sleeping near trains, according to local media.

If it weren’t for institutionalised racism, the number would be closer to zero, community members say.

One of the deceased, 40-year-old Nicole Joe, was a Navajo woman allegedly beaten by her boyfriend on Christmas Eve and left outside to die.

According to weather records, the temperature in Flagstaff was well below freezing in the early hours of December 25.

‘A little help’

“My sister, she had the hardest time here in this town,” Nicole’s sister Sophie Joe, who spoke at the rally, told Al Jazeera.

But opportunities in Flagstaff are scarce for Native people with low levels of education and substance abuse problems, she added.

Sofie and Nicole arrived in Flagstaff in 2002 after their parents separated. They experienced racial profiling from police, homeless shelters, and employers, she said.

Sophie said she “decided to straighten out” her life about five years ago and gained employment – difficult to do after a drunk driving conviction – and a house in 2014.

Nicole experienced homelessness until the end of her life.

“[She] tried really hard. She was in and out of rehab. She’s got two kids – a 12-year-old and 7-year-old daughter. That’s who she was striving hard for,” Joe said about her sister.

Nicole had been on waiting lists for permanent housing for years through a number of charities in the region, though it never materialised.

Sofie also said shelters in the city often turned her and her sister away.

There are at least five shelters in Flagstaff, most of which do not house those dealing with substance abuse or mental health issues.

“We’ve got people in here that are truly the most likely to die on the street tonight,” Ross Altenbaugh, executive director of the Flagstaff Shelter Services (FSS), told Al Jazeera in a 2016 interview.

FSS recognised the issue and started an overflow programme, partnering with others in the community to open more sleeping space.

The programme has been attributed with the decrease in exposure deaths. Eight unsheltered people died in 2017, down from 12 in 2016 and 10 the year before.

FSS also works to address the root causes. “The answer for us is housing,” Altenbaugh said.

Once someone has steady shelter, “you have a much stronger chance of working through issues such as substance abuse. You can’t expect people to get clean living in emergency housing”.

But Nicole Joe never had the chance to work through her issues, her sister said.

“All she needed was a little help,” which Flagstaff did not provide, said Sofie.

Unfriendly city

Flagstaff has a long history of attempting to remove homeless people from its tourist-friendly downtown area.

The city was listed as the 10th-meanest in the US for those experiencing homelessness by the National Coalition for the Homeless because of anti-camping laws.

In 2008, the city worked with businesses and the Flagstaff Police Department (FPD) to adopt Operation 40, a law that classified the act of asking for spare change or food as loitering, a misdemeanour offence.

According to the FPD’s annual reports from 2010 to 2012, it was a great success. The 2011 report said Operation 40 “continued to be successful as 229 arrests were made”. In 2012, the FPD credited the statute with dropping crime rates by six percent.

But the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) challenged the law with local attorneys in 2013 claiming it was unconstitutional following the arrest of a homeless woman from the Hopi Nation.

Marlene Baldwin was arrested for asking an undercover police officer for $1.25 for bus fare.

At the time, Baldwin was in her mid-70s, stood less than 1.5 metres tall, and was losing her eyesight, according to a release by the ACLU.

“She was actually arrested twice, once for bus fare and again for asking for a hamburger,” Robert Malone, a private lawyer who worked on the case, told Al Jazeera during an interview in his Flagstaff office.

The local jail became a “revolving door”, according to Malone, with most people arrested and kept for a short time.

“Merchants didn’t want tourists to be put off by the presence of these people. It was to discourage them from being where they were,” he said.

The state lawyer chose not to defend Operation 40 because of its infringement on freedom of expression guaranteed in the US Constitution and the law was scrapped.

‘No one is homeless’

Although Operation 40 ended, Klee Benally, a musician, filmmaker and activist with local organisation the Taala Hooghan Infoshop, which assists the unsheltered, told Al Jazeera that discrimination in Flagstaff, and the wider US, is far from over.

![The Taala Hooghan Infoshop assists the unsheltered in Flagstaff [Creede Newton/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/0445dc0a7783412e87b8fd771e482297_18.jpeg)

Organisers met in January for the Women’s March in Phoenix, Arizona, to draw attention to the problem of missing indigenous women.

Though a huge issue according to Native communities, the US currently has no way of tracking missing and murdered indigenous women.

Figures for indigenous people experiencing homelessness are similarly scant because of issues such as small population size and geographic dispersion.

The most recent official estimates date back to 2003, when the US Commission on Civil Rights placed it at 90,000.

According to the National Coalition for the Homeless, in 2009 indigenous people accounted for four percent of the country’s 656,129 unsheltered persons while being roughly one percent of the national population.

Flagstaff, which is an example of the treatment Native people receive across the US, “has a lot to come to terms with in its treatment of Native people in general”, Benally said.

“No one is homeless. Mother Earth is our home… It’s not idealised, that’s who we are. It’s not an issue of hope, it’s in our DNA as survivors.”