Myanmar’s Suu Kyi opens fresh round of peace talks

Delegates seek to revive country’s faltering peace process amid some of the worst violence in years.

Myanmar’s leader Aung San Suu Kyi has opened a new round of talks aimed at reviving a stuttering peace process after months of intense regional fighting.

|

|

Hundreds of representatives from some of Myanmar’s biggest ethnic groups gathered in the capital city of Naypyidaw on Wednesday for a five-day conference.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘I won’t serve’: Myanmar people plan exit to escape military draft

Myanmar’s rebels see unity as key to victory over weakened military rulers

Concerns raised over Myanmar’s ailing Aung San Suu Kyi

The discussions are Suu Kyi’s second attempt to end fighting in the country’s troubled frontier regions, where various ethnic groups have been waging war against the state for almost seven decades.

The previous round of negotiations, which took place in August 2016 and was organised by the Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD), was welcomed with great optimism by many, including the then United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon.

But the latest talks have been met with some scepticism as there has been little progress since Suu Kyi took power more than a year ago.

Al Jazeera’s Florence Looi, reporting from Naypidaw, said a major obstacle at the talks will be a landmark ceasefire accord – known as the National Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) – that was negotiated by the previous administration.

“Only eight ethnic armed groups have signed the deal,” Looi said. “Those who haven’t signed will only be able to attend this round of talks a special guests, not as participants.”

READ MORE: The trouble with Aung San Suu Kyi

Richard Horsey, a Yangon-based analyst and former United Nations diplomat, told the Reuters news agency that “it’s unlikely that any new groups would sign the NCA, but they will discuss a set of potential consensus points”.

Sai Kyaq Nyunt, a member of the Shan National League for Democracy, told Al Jazeera that without full participation from all ethnic groups, “important issues should not be decided”.

Mg Mg Soe, an ethnic affairs analyst, said, however, that “the most important thing in the current situation is to be able to hold a meaningful conference”.

Among the groups attending the talks as “special guests” are seven that have refused to sign up to the government-backed ceasefire.

READ MORE: Myanmar’s democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi has lost her voice

Representatives from all seven, including the United Wa State Army – Myanmar’s largest nonstate armed group – Kachin Independence Army (KIA), the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), the Arakan Army (AA), the Shan State Army-North (SSA-N), the National Democratic Alliance Army, and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), touched down in Naypyidaw on Tuesday after weeks of fraught negotiations.

Three of those groups – the AA, TNLA and the MNDAA – were previously excluded from peace negotiations.

The United Nationalities Federal Council (UNFC), another coalition of armed groups, has refused to attend saying it had not been granted an “equal” place at the table.

Many armed groups have complained that Suu Kyi has not listened to their concerns and is working too closely with the military, which ran the country with an iron fist for almost half a century and was widely loathed by rebels.

When Suu Kyi took charge of the peace process last year, she dismantled a peace centre set up by the previous government that was leading talks with the rebels. Some observers say the move undermined the trust built up over the years.

“They should do more informal meetings. And the peace brokers between the groups, I think the government should recognise them and expand their role,” Aung Thu Nyein of the Myanmar-based Institute for Strategy and Policy said, referring to informal peace negotiators.

READ MORE: UN to ‘urgently’ probe crimes against Rohingya Muslims

Among issues on the agenda for the peace talks are whether the states that make up Myanmar would be allowed to draft their own constitutions and the status of religion, a move that some say is a “historic milestone” for Myanmar.

“In a way, it is a historic milestone in the post-colonial history of Myanmar and represents a new level of federalism,” Angshuman Choudhury from the Delhi-based Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies said.

“It is a strategic move by the union government to appease powerful ethnic constituencies and … prevent outright secessionism.”

Renewed violence

The talks come as violence in the northeast reaches its worst point since the conflict-ridden 1980s.

|

|

“I want to hope for the best. But this is not an easy process,” an ethnic Shan woman told Reuters in Yangon. “No side wants to change their current position and lose or reduce their power and opportunities.”

Hundreds of thousands of people have been forced to flee months of heavy fighting between the army and rebel groups, many of them crossing into neighbouring China.

The violence has destroyed much of the fragile trust minority voters placed in Suu Kyi in the 2015 vote, and her NLD party has suffered several losses in recent by-elections.

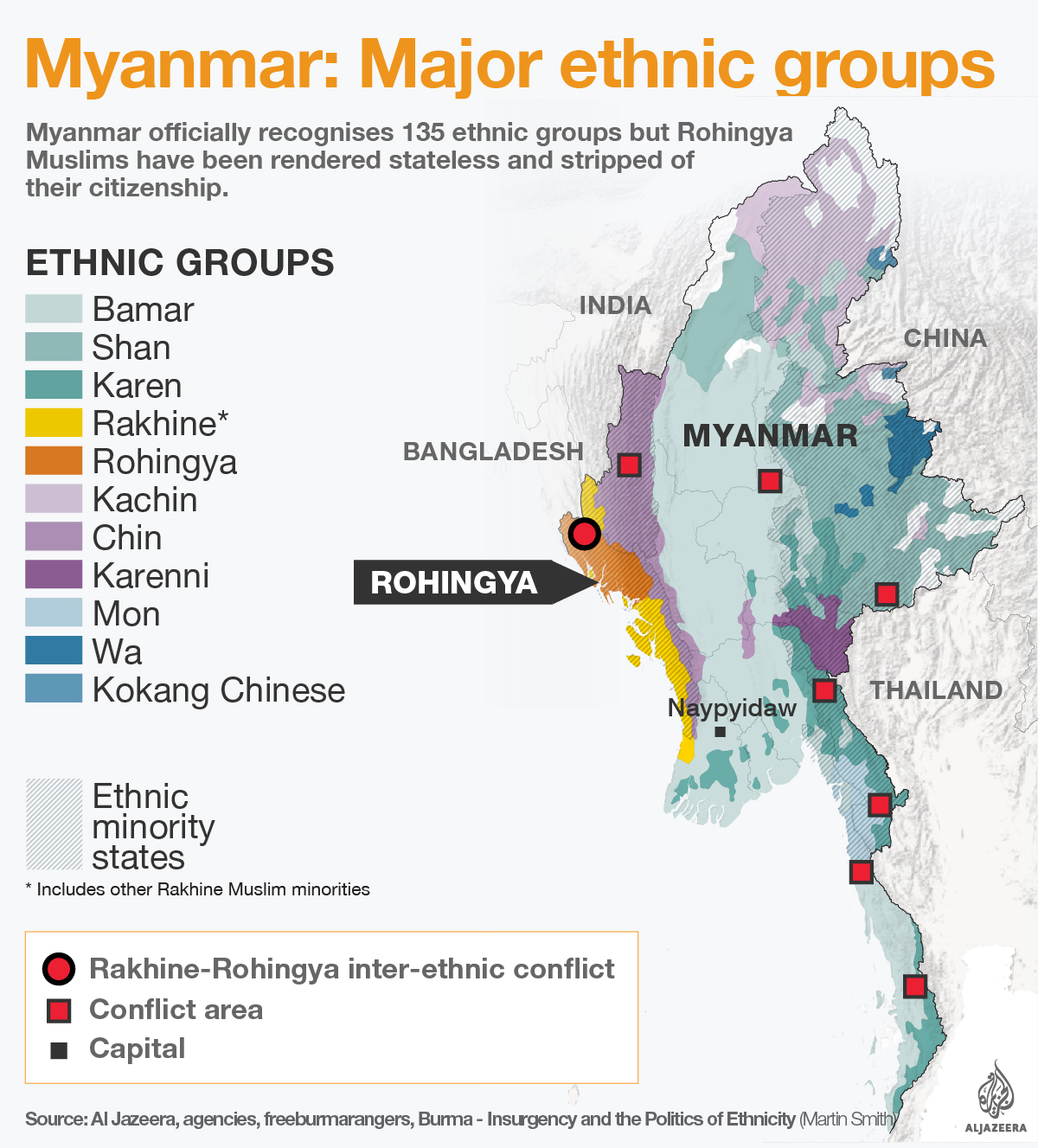

The conflict in northwestern Rakhine state, where an army crackdown on what the government calls armed men has forced 75,000 Rohingya Muslims to flee to Bangladesh amid allegations of widespread atrocities, is separate from the peace process and will not be discussed at the conference in Naypyidaw.