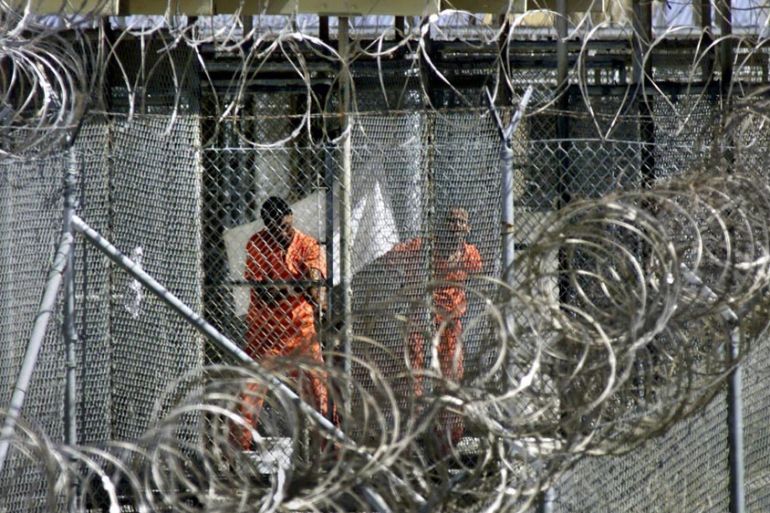

Guantanamo: The last-chance hearings

Upcoming detainee reviews highlight the plight of dozens of men languishing in US prison, some for more than 15 years.

Karim Bostan was forced to flee his village in Afghanistan during the Soviet invasion and spent his formative years as a refugee in Pakistan.

In the early 1990s, Bostan made his way back to his home country to start anew. He married and had six children – one of whom, a girl, died in infancy. Bostan’s youngest child was born after he was detained and then imprisoned by the United States in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMyanmar’s Aung San Suu Kyi moved to house arrest amid heatwave

‘Joyful but afraid’: Disabled Indian academic Saibaba’s family on acquittal

Gangs in Haiti break thousands of inmates out of prison

The US alleges that he was “probably” an al-Qaeda member. After 15 years, they’re still not sure.

Bostan is one of nine Guantanamo prisoners scheduled to have a parole-style hearing in May. These hearings have picked up significantly in pace with 21 having taken place by the end of the month. In all of 2014, only eight cases were heard.

Bostan made his plea for release on May 3. The prison’s only Kenyan citizen and another man who has been held since day one will also appear before the Periodic Review Board (PRB) this month.

|

|

| Inside Story – Guantanamo: Will it ever close? |

President Barack Obama tried to make light of his failure to close Guantanamo at the recent White House correspondents’ dinner by chiding Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump.

“There’s one area where Donald’s experience could be invaluable – and that’s closing Guantánamo … Trump knows a thing or two about running waterfront properties into the ground,” joked Obama.

But with time running out on his presidency, it is hard to imagine that the men – most of whom have been held at the prison for 15 years without charge – will find humour in their situations.

Trump, who said we “should go tougher than waterboarding“, could potentially win the White House.

Prisoners’ best chance

The hearings are proving to be the prisoners’ best chance of leaving the infamous US prison. In contradiction to the president’s stated desire that he wants to close the site, his Justice Department has consistently opposed the prisoners’ releases by fighting their habeas petitions.

“In June 2008, the Supreme Court ruled Guantanamo prisoners have a constitutional right to challenge the grounds for their detentions in the federal courts.

“But judges on the DC circuit quickly handed down a series of decisions gutting that right – ruling [detainees] …have no substantive right to due process of law, and that any evidence presented against them must be presumed to be true,” according to lawyer Tom Wilner, who was a counsel of record for Guantanamo detainees in that 2008 case.

“Since these decisions, not a single habeas petition contested by the government has been granted, and every prior district court grant of habeas has been reversed,” noted Wilner.

The prison now holds 80 men. Ten are in various stages of military commission proceedings and 26 are cleared for transfer. A further 44, sometimes referred to as the “forever prisoners”, are not cleared for release, but have also not been charged with a crime.

READ MORE: US sends nine Guantanamo detainees to Saudi Arabia

The Periodic Review Board is a six-agency panel that includes officials from the Joint Staff, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Defense, Homeland Security, Justice and State Departments. The board has ruled in favour of the prisoners about 70 percent of the time. Nine of the men once deemed “too dangerous to release” but were then cleared by the board are either back home or resettled in a third country.

There has even been a recent US admission of mistaken identity that kept one prisoner locked up for more than a decade and the man is still there.

As of May 1, only eight men have lost their appeals, including a now-prolific artist Muhammad al-Ansi. He is among the last men held from the so-called “Dirty Thirty”, a group accused of being the security detail for former al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden.

When Ansi travelled to Afghanistan in 2001, he was not yet 20 years old. Further, “he lacked the strategic or technical skills required to plan or carry out any threatening attacks” against anyone, according to what his lawyer Lisa Strauss told the board.

The board, however, decided “continued law of detention remained necessary” citing the prisoner’s “lack of candor resulting in an inability to assess the detainee’s credibility and therefore his future ‘intentions’“.

Yet Yemeni prisoner Majid Mahmud Abdu Ahmed – alleged to have committed the same offenscs – was given the okay for transfer. The Defense Department accused at least three other “forever” Yemeni prisoners of the same near verbatim allegations as Ansiand Ahmed faced, according to Department of Defense files released by WikiLeaks.

One of those prisoners is awaiting his initial PRB hearing, another is awaiting the results and a third, Moath al-Alwi, who lost his appeal in front of the board, reportedly was on the receiving end of non-lethal gunshots while imprisoned.

These five Yemeni men were young when Pakistani forces captured them in mid-December 2001 while attempting to cross the Afghanistan-Pakistan border. Analysts do not think all these “Dirty Thirty” men could have been bodyguards for bin Laden.

“I doubt it very much,” said Ahmed Rashid, a journalist and expert on the region. Bin Laden’s bodyguards “knew him for a decade or more, some he even brought from Sudan. I doubt if he would have hired new guys.”

However, it’s not hard to deduce from the publicly available “evidence” why the US has concluded it would be hard to obtain a conviction in their cases, because there is little of substance in them and because some of the main charges come from men who were tortured or were found to be unbelievable.

Admitting ‘guilt’

US Defense Secretary Ashton Carter, “does not transfer a detainee unless he is confident that the threat is substantially mitigated and it’s in the national security interests of the United States”, said Paul Lewis, special envoy for Guantanamo detention closure.

But it is not clear how the “threat” these men pose is being determined. The PRB is described as “a discretionary” process that “does not address the legality of any individual’s detention”.

While it is hard to assess what happens in the classified reviews of the prisoners, an analysis of PRB statements by Al Jazeera seems to suggest that, in part, the board wants to hear prisoners “admit” past mistakes, “accept responsibility”, and not have “anger at the US”.

However, it is a risk if a prisoner makes a statement accepting “guilt” when there is none, as his statement could be used against him either in a future trial or hearing by the US, or by a country where the prisoner may be repatriated or transferred, noted Wells Dixon from the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), which represents several Guantanamo prisoners.

READ MORE: The dark prisoners – Inside the CIA’s torture programme

There seems to be this sense, even in the government, to try to cast this “war on terror” in terms that people are familiar with, for example calling the PRB “parole-like” hearings, said David Glazier, a professor of law at Loyola Law School, who follows Guantanamo developments.

“But what I think people in the government are forgetting with respect to Guantanamo is that these folks have never been proved guilty beyond a reasonable doubt,” Glazier said.

Once a US court in an American criminal setting “has found – as a matter of law – that the individual has committed a crime, it seems perfectly reasonable [for] a parole board … to expect the individual to show remorse”, added Glazier.

“But what is missing … is the fact that many of these folks, in fact, probably never were truly associated with al-Qaeda. And if they have to lie in order to admit responsibility for things they haven’t done and show remorse for conduct that they haven’t engaged in order to be released, it shouldn’t surprise us that some of them … do that.”

The US government’s expectation that the prisoners be compliant is also interesting to Glazier. According to the code of conduct for American service members, they “are under lawful orders to continue to resist once they are detained and yet we criticise the Guantanamo detainees for being difficult captives when that is exactly what we expect of American personnel in parallel situations”.

Torture and hearings ahead

There are tougher hearings on the horizon, including that of “Guantanamo Diary” author Mohamedou Slahi and Mohammed al-Qahtani, the only Guantanamo prisoner the US government openly admitted was tortured.

The latter survived the “First Special Interrogation Plan” that was given the okay by former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, after which Qahtani – who the US alleges was an intended hijacker in the September 11 attacks – was caged in solitary confinement for five years.

Qahtani belongs to “a theoretical group of detainees remaining at the base who the government somehow knows are guilty but cannot prosecute because the only evidence against them is tainted by torture”, according to the Center for Constitutional Rights, which represents him.

“The fact is, if the only evidence against an individual is obtained through torture, there is no reliable evidence. Period.”

Follow Jenifer Fenton on Twitter: @jeniferfenton

|

|

| Guantanamo’s Child – Omar Khadr – Witness |