A century on: What remains of Sykes-Picot

Two historians debate the agreement’s legacy.

Al Jazeera speaks to two historians; Roger Owen and Sayyar al-Jamil on what remains of Sykes-Picot.

| Roger Owen, Professor Emeritus of Middle East History, Harvard University |

And though it was soon overtaken by the implementation of other agreements and promises – including the infamous Balfour Declaration of 1917- it has come to stand for a whole Western attempt to divide and control the Middle East by the imposition of illegitimate borders, and then by the establishment of illegitimate states based upon them.

Indeed, so great is this evil still perceived to be that it remains powerful enough to be employed to legitimise the efforts to any new group such as the Islamic State group (ISIL, also known as ISIS) to reunite all parts of Machrek into a single political regime.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsHow will the Baltimore Key Bridge debris be cleared?

Land Day: What happened in Palestine in 1976?

‘We stay together’: Yemenis tell their stories, in their own wordsThis article will be opened in a new browser window

In seeking to understand this phenomenon, two initial points are in order. First, there is a significant difference between the situation in the east and west of the Arab world with the states of North Africa, from Egypt to Morocco mostly well-established entities and, with the possible exception of Libya, with universally recognised international borders.

|

It is the internal divisions within both Syria and Iraq that now seem most salient, suggesting the likelihood, faut de mieux, of the emergence of a loose type of federal structure based very largely on ethnic and sectarian difference. |

Second, the special complexities to be found east of the Suez Canal have been magnified by a series of Western interventions, from the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 to the Anglo-American invasion, and subsequent occupation, of Iraq in 2003.

Nevertheless, a case can still be made that there is an historical “natural” order to be found in the Machrek based on three centuries of Ottoman rule, with provinces based on the major cities of Damascus and Aleppo in what became Syria, and Basra, Baghdad and Mosul in what became Iraq.

And that this natural order has been exploited more or less successfully by ruling regimes since at least the establishment of internationally-recognised Baath Party rule in the late 1960s.

Note, too, that where city-based political entities are concerned, power is located firmly at the centre, while borders, particularly those that cross deserts, mountains and other mostly uninhabited areas, remain difficult to patrol.

Nevertheless, problems concerning the legitimacy of contemporary political orders in Syria and Iraq remain in terms of both state and of regime. On the one hand, regime capacities to transform post-colonial subjects into citizens with equal rights have significant flaws due to their perceived sectarian and dictatorial character.

On the other, state capacity is – itself – underdeveloped in terms of its ability both to tax and to provide judicial and social services equally to all sections of their populations. Hence, once again, the challenge posed by ISIL, as well as al-Qaeda, not just to political divisions but also to the basic legitimacy of all existing governing regimes when viewed through the lens of religion and moral integrity.

To the late Osama bin Laden, as well as so many of his present-day followers, the “Near Enemy” in the Middle East and the “Far Enemy”, in the United States, support each other in their desire to destroy Islam.

What of the future? Rather than the political division of the Machreq as the Arab nationalists used to fear, it is the internal divisions within both Syria and Iraq that now seem most salient, suggesting the likelihood, faut de mieux, of the emergence of a loose type of federal structure based very largely on ethnic and sectarian difference, with official and unofficial checkpoints marking the boundaries in between.

For one thing, it is not in any community’s interest to run the risk of breaking away entirely, not even the Syrian and Iraqi Kurds who are heavily dependent on subsidies from each capital city.

For another, the most powerful members of the international community, notably the United States and Russia, have made it clear that the post-1945 notion of national sovereignty must continue to be respected, not to speak of the leaders of such neighbouring countries as Turkey, Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Meanwhile, difference, whether in terms of dialect, cuisine, customs and even jokes, will continue to exist, as it does now, leading, I would suggest, to more of the type of competitive patriotism, represented by such off-repeated boasts as “our mountains as more beautiful than yours”, “our cuisine more tasty”.

A region, in other words, like Europe, where armed conflict has given way to fiercely contested football matches.

| Sayyar al-Jamil, researcher and historian, author of “The Emergence of Modern Arabs” |

In my view, Sykes-Picot agreement never really matched the historical legacy of the Ottoman administrative regions that have lived for nearly four centuries.The agreement does not deserve all this historic interest by the Arabs or others.

There are many misconceptions about the Sykes-Picot Agreement. A century later, many Arabs still believe the agreement set the borders of the modern Middle East.

In fact, the map, as drawn by Sykes and Picot, only vaguely resembles the Middle East today. Instead, it defined areas of colonial domination in Syria and Mesopotamia

Second misconception is that the agreement will make us understand the current regional, civil and sectarian conflicts in the Middle East.

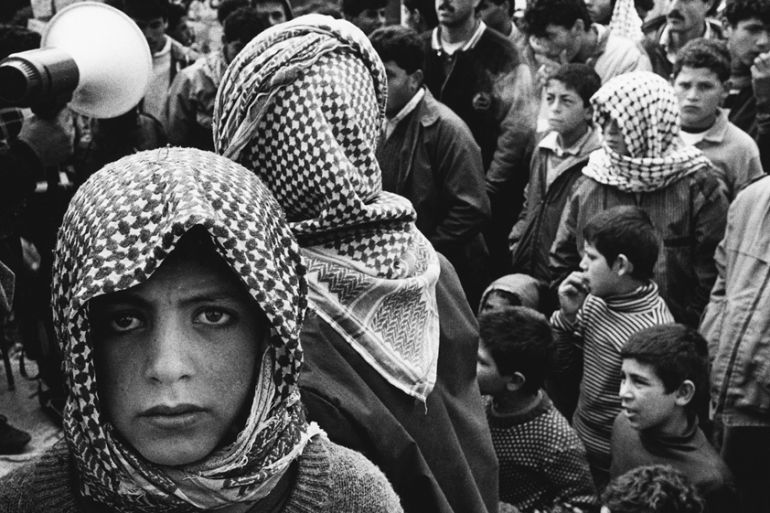

For generation after generation of Arabs, Sykes-Picot has become a byword for imperial treachery and the root cause of the region’s autocrats, foreign intruders and the growing disorder

However, this treaty was one of several interim plans that the Allies reached in the post-World War I order to divide the Ottoman legacy.

|

Sykes-Picot will remain alive in Arab memory as the main reason behind the regional disorder we are living today. |

The commonly held perception that Sykes-Picot is the source of all problems in the region is wrong because some of those problems date back much further than the treaty itself. In fact, Sykes-Picot agreement, in my opinion, has never materialised on the ground.

For example, the current borders between Syria and Iraq have been formed through other agreements after the1919 Versailles Conference. These are the borders that are taught in history lessons and that later became the signs and symbols of nationalism.

What remains of Sykes-Picot today? Not much, I would say, although strands of Arab nationalism remain powerful and effective to this day. Another Sykes-Picot legacy haunting the Arab world is how ethnic minorities were not given national rights.

However, across the Arab world, there remains a dominant perception that the reasons behind the historic impasse that the Arab world confronted a hundred years ago, remain pretty much the same: Western intervention.

I can say that the US invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003 as well as the outbreak of civil war in Syria since 2011 have both served as grim reminders of Sykes-Picot, although today there are different realities on the ground. For example, if we asked any Lebanese or Jordanian whether they want to be part of the Greater Syria or the Fertile Crescent, everyone will reject this altogether.

Nonetheless, I think Sykes-Picot will remain alive in Arab memory as the main reason behind the regional disorder we are living today.