The struggle of Italy’s ‘foreign’ footballers

Racist incidents are decreasing in Italian football, but the path to the top for those born abroad is still quite steep.

When the Ghana-born footballer Kingsley Boateng was called a “nigger” during a youth league football match in Italy, he just laughed it off.

But this incident certainly was not a one-off. Racism in Italian football remains a serious issue, and Boateng does not take it as lightly when other fellow players are victims of abuse.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsPalestinian Prisoner’s Day: How many are still in Israeli detention?

‘Mama we’re dying’: Only able to hear her kids in Gaza in their final days

Europe pledges to boost aid to Sudan on unwelcome war anniversary

“I wish Italy had moved on from this,” Boateng told Al Jazeera. “It makes me sad that it’s still happening.”

A tougher approach adopted by the country’s football association, the FIGC, has started to prove effective in curbing the menace. But social attitudes and institutional constraints continue to make it difficult for Italian players of foreign origin to reach the top of the football world.

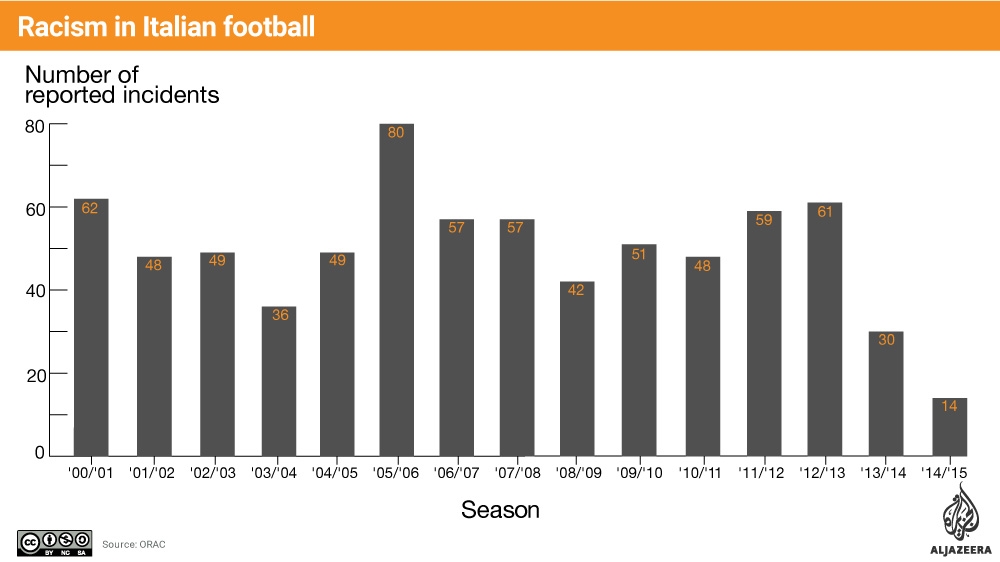

A total of 14 racist episodes were recorded across Italy’s professional leagues in the 2014-15 season, according to preliminary data from Osservatorio sul Razzismo and Antirazzismo nel Calcio (ORAC), an independent organisation that tracks media and official reports of racism in Italian football.

The figure was at its lowest in 15 years, down 50% from 2013-14 and around a sixth of the 80 episodes registered in 2005-06. Most of the offences were racist chants or booing from the crowd, but there were some instances of players being verbally abused by opponents on the pitch.

The declining trend is likely due to the “zero tolerance” approach by FIGC since August 2013, according to ORAC director and sociologist Mauro Valeri.

The new rules have brought harsher sanctions for the professional clubs whose supporters cross the line. The penalties start with the closure of sectors of the stadium and can be increased to fines of a minimum of $57,000 and championship bans in case of repeat offences.

Players’ sanctions have also been increased from a five to a 10-game minimum ban, with fines between $11,210 and $22,400.

While the decline in the professional world is encouraging, racism is more ingrained at youth and amateur levels, according to Valeri. He labelled this as one of the reasons why few Italian footballers of foreign origin have reached the top of the profession.

Long process

Boateng made his Italian under-21 debut in August but was the only such player among those summoned to join the team that will compete in the 2017 European U21 Championship. Mario Balotelli, likewise, was the only one in the national squad that played in the 2014 World Cup.

Non-EU migrants can obtain Italian citizenship if they can prove they have lived in the country for at least 10 years. They can then pass it on to their children, which is what happened to Boateng after he moved to Italy at age five.

Children born in Italy from migrant parents can only apply for citizenship between their 18th and 19th birthdays.

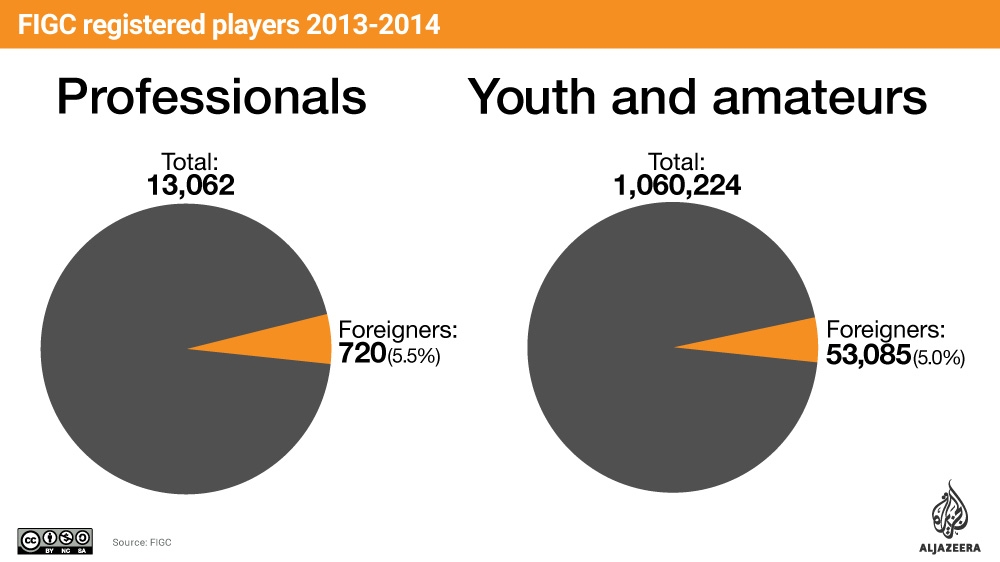

As a result, a large number remains categorised as foreigners at an administrative level for most of their early careers, with more onerous administrative requirements imposed on them.

For example, non-EU minor players are requested to provide copies of their parents’ employment contracts, passports and visas in order to register with the FIGC, and their application needs to be approved by a regional committee.

Valeri described this as “institutional discrimination” that limits the potential of football as a driver for social inclusion.

An FIGC spokesperson told Al Jazeera that its requirements were in line with those set out by FIFA and UEFA.

In contrast, Italy’s hockey and boxing federations have reformed their regulations in the last two years so that the registration of locally born, young foreigners is equivalent to the registration procedures for Italian citizens.

There is less protection for players and more ignorance among supporters. People don’t really pay attention to it.

The Italian parliament is currently discussing a law that would extend this initiative to all sports associations.

But besides bureaucratic barriers, young players with foreign names or features also face the unwelcoming attitude of some of the Italian population.

ORAC recorded at least 44 racist episodes in the non-professional sector in 2014-15, including nine cases involving insults among players on the pitch.

This is 10 fewer than the previous season, the first in which the organisation started monitoring the amateur leagues. But Valeri warned more might have gone unreported because of the less prominent nature of these competitions.

Boateng thinks it is in the non-professional sector that players are more exposed to racism.

“There is less protection for players and more ignorance among supporters,” he said. “People don’t really pay attention to it.”

This reflects confusion in the football world, but also in the wider society, on what racism means in practise.

Last July, FIGC President Carlo Tavecchio made a controversial comment about a fictitious African player, Opti Poba, “eating bananas” in an attempt to address the issue of a perceived lack of opportunities for young Italian players.

He was barred from holding any position at UEFA and FIFA for six months. However, the Italian federation dismissed his case, saying there was no “relevant evidence” for prosecution.

Similarly, in January, former national team manager Arrigo Sacchi said there were “too many black players” at youth level, which was evidence that the nation was “without dignity or pride”.

FIFA President Sepp Blatter publicly condemned the comments, but Sacchi rejected accusations of racism and was defended by some Italian coaches and players.

Racism also remains a highly politicised issue, with no clear bipartisan opposition among Italian political groups.

The right-wing anti-immigration party Lega Nord, whose slogans and manifestos have often attracted accusations of racism, was part of the country’s coalition government between 2008 and 2011.

The party has been regaining ground in the past year and won between 7 and 20 percent of votes in May’s regional elections.

But sport must not just reflect societal trends, it should also be a catalyst for change, said retired long jump Olympic medallist Fiona May, who was appointed to lead an FIGC anti-racism campaign that started in February.

![May, a former athlete, speaking at the Italian Football Federation event against racism [Getty Images]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/bd1274330f724e8098f8e5e4a3f33eb3_18.jpeg)

The Britain-born former athlete told Al Jazeera she believes the harsh line adopted by other countries in Europe might not be the best approach for Italy, and that the country’s sports’ authorities will need to find their own way to find a solution.

As part of the initiative, which she has designed, May is touring football schools around the country alongside other sport personalities and celebrities to raise awareness in 12 to 18-year-old players.

“We make it a 60-minute show,” said May. “We play clips of famous sports figures and try to explain that it is really not a question of colour. It’s about our talent and what we’re capable of doing.

“It’s Italy and it’s 2015. I wish there wasn’t a need for it. But there is, and I’m determined to go out and work on this. Even if it’s just a drop, it’s better than nothing.”

Follow Chiara Francavilla on Twitter: @ChFrancavilla