For migrants in southern Libya, a whole desert to cross

Thousands seek new routes to cross the treacherous desert to their final destination across the Mediterranean.

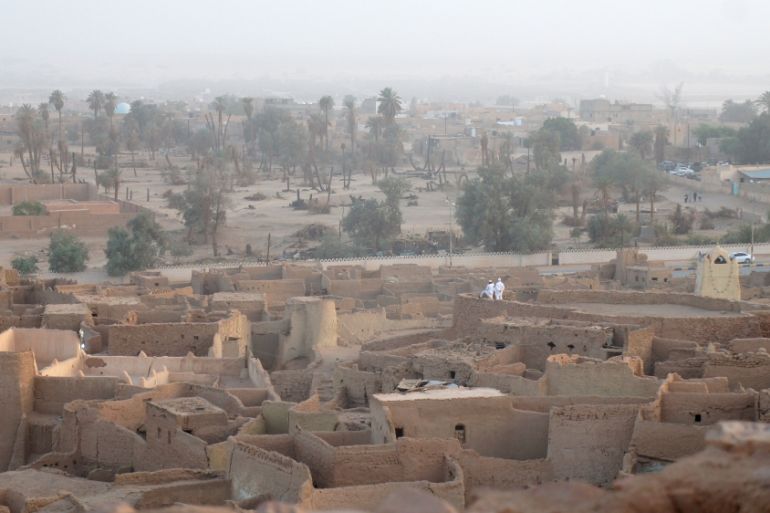

Ghat, Libya – In the shadow of Ghat’s ancient medina, a small cluster of migrants from West African and Sahel states take refuge under the hilltop fort from the scorching sun. They are searching for work, money, and a ride with people-smugglers across the desert to Libya’s north.

“There is no work here,” explained Salim, 25, from Niger, who has slept in an abandoned construction site in Ghat for the past year, and eats at the makeshift food shack next door. “We get paid little for the work we do find, but sometimes not at all.”

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsEurope pledges to boost aid to Sudan on unwelcome war anniversary

Birth, death, escape: Three women’s struggle through Sudan’s war

Mapping Israel-Lebanon cross-border attacks

Ghat is a quiet, remote, and predominantly Tuareg oasis along the Algerian border in Libya’s southwest Sahara. Historically, it was a major stop along a prosperous trade caravan route, complete with a desert slave market. The scenic Acacus Mountain chain hems in the area along Libya’s southern border.

The 2011 popular uprising that toppled the regime of Muammar Gaddafi, triggered a major flow of arms and fighters across Libya’s southern frontiers. Well-worn smuggling routes that ferry migrants across borders and across the treacherous desert have slightly shifted, with many migrants moving on routes to the east of Ghat instead.

Algeria has significantly tightened its borders with southwest Libya, cutting off Ghat’s Tuareg from their neighbouring kin. The French military presence along the Libyan border with Niger has also hampered smuggling networks.

RELATED: Libya: The migrant trap

According to Othman Belbeisi, Libya chief of mission at the International Organization for Migration (IOM), as of May 21, 39,640 people had arrived on Italian shores from the sea. There have been an estimated 1,800 deaths at sea so far this year.

Last year more than 170,000 migrants successfully crossed the Mediterranean,142,000 of whom departed from Libyan shores for Italy, according to Belbeisi. More than 3,000 deaths at sea have been recorded.

Summer is peak season for ocean crossings, with many boats being launched by smugglers from the northeast Amazigh town of Zuara on the coast.

Key international organisations that deal with asylum seekers and migrants, such as the United Nations

Here is a desert gateway to Libya. We are in a transit state. Now we have up to twenty people here, sometimes up to forty. You never know when they are going to move north - their goal is going north.

refugee agency and IOM are now headquartered in Tunisia, along with other international charities. Their activities are strictly curtailed and limited.

In 2014 the Italian search and rescue operation, Mare Nostrum, plucked around 100,000 migrants from the sea. Branded a controversial “pull factor” for migrants to Europe, the programme closed down late last year, to be replaced by expanded patrols by the EU border agency Frontex.

While European leaders are wrestling with ideas to deal with migrants reaching their shores, including military strikes on smugglers along the seashore, their high-profile failure to launch their border advisory and training mission in Libya after the revolution, and the virtual absence of an official Libyan border patrol along its southern frontiers, is striking.

An aggressive French military presence along Libya’s border with Niger and Algeria has tamped down smuggling activity through a dangerous desert stretch called “Salvador Pass”.

France has established a military base in Mandama, Niger, 100km from Libya’s border, in what it says is a bid to combat terrorism. The US also has a military base in Niger.

Now more smugglers channel the mostly West African migrants across Libya’s porous southern borders towards southern Libya’s main desert city of Sebha, in an area dominated by indigenous Tebu and Arab tribes.

The isolated oasis of Kufra is another major hub along smuggling routes, which channels many of those fleeing wars in Somalia and Eritrea, and poverty in Ethiopia.

RELATED: Libya grapples with migration crisis

![Asmara recently paid $800 to travel from Liberia to Ghat [Rebecca Murray/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/6b659f4f836b4d48b77986742725ec38_18.jpeg)

In a makeshift church, tucked along an alleyway in a poor neighbourhood of Ghat, a Nigerian priest called “Brother Eugene” has just finished an English-speaking sermon with his small congregation. Musical instruments crowd the small altar, and handwritten notes advocating the fair treatment of women line the walls.

Eugene, a longtime resident of Ghat, spoke cautiously, and was careful to thank Ghat for its hospitality. “Here is a desert gateway to Libya,” he explained. “We are in a transit state. Now we have up to 20 people here, sometimes up to 40. You never know when they are going to move north – their goal is going north.”

The Libyan interior ministry’s Department for Combating Illegal Migration (DCIM) controls 19 detention centres

|

|

around Libya. However, those in the bigger southwest towns of Ghat, Ubari and Murzuq are shuttered. Only a recently rehabilitated centre in Sebha is open.

Misratan military authorities in the area told Al Jazeera that migrants and asylum seekers are being bussed from the north to Sebha, with ultimate plans for them to be dropped off across the border in Niger.

Meanwhile, Amnesty International has reported gruesome migrant testimonies of being abducted, imprisoned and tortured for money in privately owned premises by militias are common.

The two parallel government structures in Libya add to the crisis. General Khalifa Haftar and the Tobruk government, recognised by much of the international community, argue for a lifting of the international weapons embargo to better combat smugglers and terrorism.

Meanwhile, the Tripoli-based government has acknowledged that it is overwhelmed in its effort to combat migration, and has offered to team up with European countries to do so.

“The goal for Libya Dawn is to get international credit by reducing the level of migration, and asking for indirect international recognition,” said one European diplomat close to the current United Nations-led peace talks for Libya.

Far away, on a dusty field in Ghat, Asmara, a Liberian professional footballer, talks about his personal dreams. Once recruited to play in Russia with a Moscow team, he said the experience was life changing, but he didn’t get a contract.

Asmara recently paid $800 to travel from Liberia to Ghat, and has been talking to “Arab football agents” online about a job.

For him, the focus is on being paid to play and to survive, and not the Saharan journey he just experienced, where “no one feels for no one”.