Iraqi Christian refugees trapped in limbo

More than 4,000 refugees have found safety in Amman, as aid agencies struggle to provide long-term solutions.

Amman, Jordan – Amnar knew to run when the church bells sounded in the middle of the night.

Shelling rang throughout the city as fighting between Kurdish Peshmerga forces and Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) fighters raged on. The Peshmerga assured residents the situation was under control, there was no need to leave.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsPalestinian Prisoner’s Day: How many are still in Israeli detention?

‘Mama we’re dying’: Only able to hear her kids in Gaza in their final days

Europe pledges to boost aid to Sudan on unwelcome war anniversary

“Around 11pm, the Peshmerga fell back and didn’t tell us anything,” Amnar, a Christian from Iraq’s northern city of Qaraqosh, told Al Jazeera.

“We heard a bell telling us: ‘Get out, ISIL is coming.’ We just took our clothes and some of my wife’s gold and sold it for a visa to come to Erbil.”

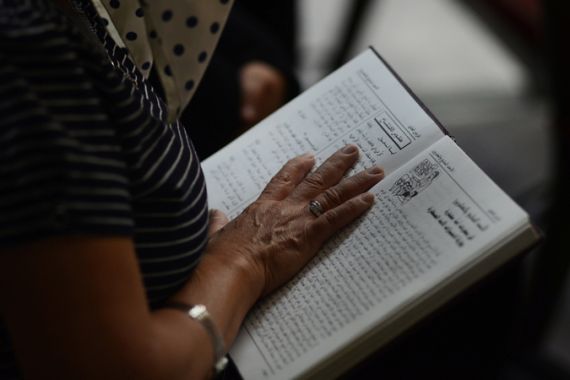

Giving only his first name fearing harsh repercussions back in Iraq, the 30-year-old art teacher recounted the events in the Latin Church of Marka, on the outskirts of Jordan’s capital, Amman. He is currently one of at least 4,000 Iraqi Christians who’ve found refuge in the kingdom since August.

We heard a bell telling us: 'Get out, ISIL is coming.' We just took our clothes and some of my wife's gold and sold it for a visa to come to Erbil.

‘Convert, flee or face execution’

When ISIL began storming cities in northern Iraq in June, Christians were given a now-familiar ultimatum: convert, flee or face execution.

The initial ISIL siege raged in Mosul, but in neighbouring Qaraqosh, Iraq’s largest Christian city around 400km north of the capital Baghdad, Amnar’s family stayed put, confident in the Peshmerga’s defence.

However, on August 6, the Kurds lost ground, leaving Qaraqosh’s 50,000 residents exposed. Amnar and his wife grabbed their two toddlers and started running.

An hour later, ISIL stormed the town.

After a short stay in Erbil, Amnar fled to Jordan, reaching the city of Amman in September. Refugees like Amnar have fled to Amman with the help of Caritas Jordan, part of the worldwide Catholic aid confederation Caritas Internationalis.

Most families arrived in the country with little more than what they could carry. Caritas Jordan has provided them with food, medical assistance, and shelter at local churches.

Moving to the kingdom was a solution borne out of need. The organisation’s initial plan was to briefly house 1,000 people from Erbil, but two months on, what began as a short pit stop for the refugees on their way to more permanent resettlement solutions has become an odyssey with no clear path forward.

Fifty-three-year-old Aziz from Mosul, who did not want to give his last name for fear of reprisal, was one of the first Iraqis to arrive at the Latin Church in Marka in August.

“I, my grandparents and their grandparents, we’ve lived in Mosul until Daesh,” he told Al Jazeera, using the Arabic term for ISIL.

It was not the first time Aziz was forced to leave his home. During the height of the sectarian violence in 2009, ISIL fighters drove him from Mosul four times. But July was different.

“On July 17, my friend came and told me I had to leave [Mosul] because Daesh said it was part of the caliphate. They told me it was no longer my country,” he said.

By the time Aziz and his two children boarded a bus for Erbil four days later, ISIL had established checkpoints along the road. He said fighters speaking in different Arabic dialects stormed the bus and ordered all the Christians to get off.

“They searched our bag and took … gold, money, paperwork, everything,” he said. “They held a gun to my head and said they would kill me if I moved. Only the two pieces of clothes on my back was what they let me keep.”

Until about a month ago, both families were staying in the Latin Church before moving into a shared apartment arranged and paid for by Caritas Jordan. They split two bedrooms between nine family members.

Like many other Iraqis, Aziz is applying to be resettled in Europe.

“In general for Caritas, the situation here is temporary, we don’t know for how long,” Caritas Jordan’s communication officer, Dana Shahin, told Al Jazeera. “They all want to be resettled in another country.”

Dwindling resources

The last two months have seen the aid organisation’s original 1,000 Iraqis balloon to more than 4,000, and no one has left yet.

UNHCR’s representative in Jordan, Andrew Harper, warns that while families can’t return to Iraq any time soon, waiting for resettlement abroad could take just as long.

It's extremely unlikely that refugees coming from Iraq will be resettled any time soon.

“It’s extremely unlikely that refugees coming from Iraq will be resettled any time soon,” the UN official told Al Jazeera. “Given the security checks that governments are putting in place now, it’s going to become even more time consuming.”

Harper said more than 3,000 Iraqis registered as refugees in September, the highest monthly intake they’ve seen since 2007.

With 620,000 Syrian refugees already in the country, Jordan’s capacities are wearing thin. As priorities shift from humanitarian aid to security for the region, Jordan could lose the international support enjoyed over the last two years.

“We’re already seeing a very significant change in the rhetoric from states that generally back Jordan,” Harper said. “This makes our job much more challenging because throughout the region the security imperative is overwhelming the humanitarian imperative.”

No long-term solution

Recently in Marka, children, elderly couples and young parents tugging infants shuffled into the Latin Church’s event hall to eat lunch. Iraqi women worked in shifts to prepare meals for the approximately 200 people residing in the church and surrounding shelters.

Around 20 families have moved into apartments, but at least 50 are still sleeping at the church. Harper said 150 Iraqis register with the UNHCR every day in Amman, a number he believes will most likely increase.

Despite Caritas’ support and donations pooled by the churches, resources are running dry.

“All of us are really worried about the situation because the little that we have, I don’t know what we can do to support all these families,” Khalil Jaar, a priest at the Latin Church said. “We don’t know what to do.”

Jaar estimates the funding will last for another two months before completely running out.

Iraqis who register as refugees are not allowed to work in Jordan, they go through the UNHCR’s Refugee Status Determination (RSD) process to assess their resettlement plans. This process could take several months.

Whether or not they’re able to find resettlement abroad, staying in the country without an income is not a sustainable long-term solution for the refugees.

“I cannot stay in Jordan because the government doesn’t let me work, there is no future for my children to learn or to live,” said Fadi Khaery, a 34-year-old security guard from Bashika, a village just outside Mosul.

Khaery, his wife and two children fled to Erbil in August after clashes between ISIL and the Iraqi military landed outside Bashika’s borders.

In September, he sold the family car for enough money to get a flight to Amman and three-months worth of rent for himself, his wife and two children in Marka.

Khaery arrived in Jordan with $2,500. Just one month later, they’re down to $100.

“How can I eat after this $100 has finished?” Khaery said, opening his wallet to show the US note.

“This is the first time I’m relying on the church or someone to help me because I don’t know what I will do, and, unfortunately, no one does.”

Follow Alisa Reznick on Twitter: @AlisaReznick