Nunavut and the future of Canada’s Arctic

Inuit challenge Canadian government over failures on Nunavut deal’s 20th anniversary.

Iqaluit, Canada – Royal Canadian Air Force jets will streak across the arctic sky on Tuesday, part of celebrations marking the 20th anniversary of the agreement that created Nunavut, a northern territory home to about 30,000 native Inuit people.

It was the largest indigenous land claim in Canada’s history covering 2 million square kilometres, or about eight times the size of the United Kingdom.

But as the fighter jets fly high in the sky to mark the day, on the ground the celebrations will be modest. About 50 percent of the Inuit live in dire poverty, one-third reside in overcrowded and dilapidated housing, and half cannot afford to buy enough food to eat.

The people of Nunavut will on average live 10 years less than others across the country. Canada is tied for fourth in the world in life expectancy, but if Nunavut were a country, it would be 67th, ranking near Nepal and Tajikistan.

The scene in the capital Iqaluit will be a microcosm of the Canadian government’s approach to Arctic sovereignty. While Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s Conservative government has pledged hundreds of millions for new military infrastructure to assert Canada’s claim to the resource-rich Arctic, it has focused less on socioeconomic development in Nunavut, though it states otherwise.

“This Government is committed to ensuring that Northern economic development occurs in a way that directly involves those who live and work in the North,” said John Duncan, Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development.

Since the 1970s, the Inuit have changed the face of Canada and established a unique international cultural presence through music, films and visual art, while bolstering the use of Inuktitut, the Inuit language, at home.

Many Nunavummiut are preoccupied with day-to-day survival, but a young, educated and ambitious minority is intent on guiding what is still in many ways a nomadic hunting civilisation out of poverty.

Nunavut finds itself at the confluence of some of the largest resource extraction projects. Multibillion dollar iron and uranium mines have been proposed, and trillions of cubic metres of natural gas and major oil reserves lie offshore.

At the same time, the greenhouse effect is literally changing Nunavut’s landscape as sea ice melts, glaciers dwindle and southern plant and animal species follow warming temperatures north.

‘Founding father’

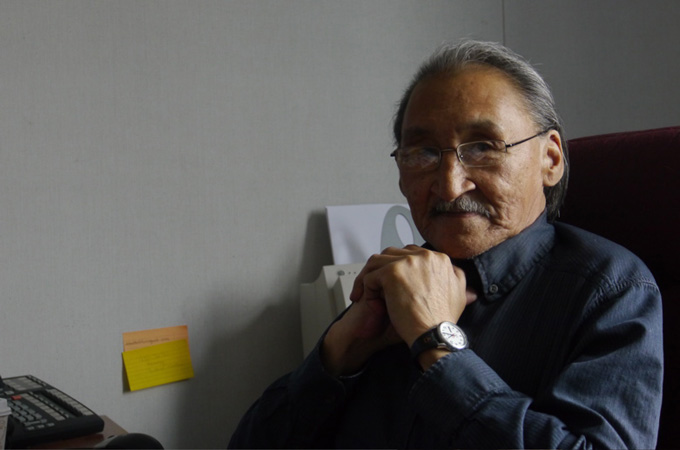

John Amagoalik is often called a “founding father” of Nunavut, though he doesn’t seem happy when he’s asked about it. Seated in his small office in the capital Iqaluit with a population 8,000, he explained the origins of Nunavut.

“We were fearing a government that had assimilation policies, that was trying to wipe out Aboriginal people in Canada,” Amagoalik told Al Jazeera. “We wanted to have more control over our lives … Our language and culture were in jeopardy as we saw it.”

Before the 1950s, Inuit were self-sufficient. They survived in the extreme arctic climate for thousands of years with a culture based on hunting, cooperation, sophisticated technology, and close observation of the land, sea and ice. For centuries, Canadian officials could not survive in the north without Inuit help.

|

| Fifty percent of people in Nunavut live in poverty [Dru Oja Jay] |

But in the post-World War II expansion, the Canada government exerted itself. Children were taken from parents and placed in residential schools, where they were punished for speaking Inuktitut and often physically and sexually abused. Families were misled or coerced into permanent settlements. Dog teams, the main means of travel in the winter, were slaughtered by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

The results were devastating, but Inuit have remained resilient and innovative.

By the 1960s, oil-and-gas exploration was booming in the Arctic. Amagoalik recalled “planes taking off and landing every few minutes” in the remote community of Resolute Bay.

Some Inuit leaders realised that by invoking their constitutionally enshrined rights to the land, they might be able to influence these operations. This leverage forced the Canadian government to the negotiating table, and 20 years of dialogue ensued.

Historic agreement

When the two parties signed the Nunavut Land Claim Agreement on July 9, 1993, the Canadian government got – and the Inuit gave up their rights to – about 25 percent of its total landmass. In return, Canada was obliged to provide Inuit of Nunavut with long-term support for self-government, education, job training, and to consult them on the use of Arctic lands.

|

| Inuit leader John Amagoalik at his office in Iqaluit [Dru Oja Jay] |

Nunavut has its own government today, but it is dominated by Qallunaat, non-Inuit, many of whom have little interest in their priorities or speaking their language.

Employing non-Inuit costs the government an estimated $137m per year in direct costs such as transportation and housing. With most of that money being spent outside of Nunavut, the long-term impacts on the economy are incalculable. By contrast, Canada has spent only $40m implementing the Inuit employment requirements of the agreement in the last 20 years.

In 2006, Nunavut Tunngavik Inc (NTI), the governing body for Inuit in Nunavut, filed a $1bn lawsuit against the government of Canada, alleging it failed to follow through with its obligations under the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement. The lawsuit is still before the courts.

“There are a number of areas that continue to be areas of concern for NTI,” said its CEO James Arreak at his office. “Canada has not come to the table in the same manner that the Inuit have. Canada got everything it wanted as soon as it signed the Land Claim agreement. Inuit are still waiting.”

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, the agency in charge of implementation of the Nunavut Land Claim, did not return requests for comment by publication time.

A new partner?

As Inuit look for new sources of leverage, some are looking beyond the windowless courtrooms of Ottawa, where the lawsuit is likely to spend several more years.

Kowesa Etitiq is among those who believe Nunavut should look beyond the Land Claim, including making a new deal with a nation other than Canada.

“If Canada isn’t living up to the agreement, we should have the opportunity to renegotiate … We shouldn’t limit ourselves to talking to Canada, either. All the options should be considered,” Etitiq said.

|

| Climate change is affecting Canada’s arctic [Dru Oja Jay] |

Inuit leaders are unlikely to formally negotiate with Russia or China anytime soon, but international leverage might be the best way to put pressure on the Canadian government.

Countries are jockeying for influence over vast natural gas deposits under the Arctic ocean. Climate change is also opening up international shipping lanes that could cut thousands of kilometres off of routes from Asia to Europe.

“Canada hasn’t done much in the way of bringing the Inuit into the fold,” said Etitiq. “Nunavut will get infrastructure when it can pay for herself.”

Madeleine Redfern, a former mayor of Iqaluit, said in Greenland Inuit there have much more autonomy, and their situation could be a model to follow.

“I think we’re going to see an increase in awareness among Canadian Inuit of the value of independence,” Redfern said by phone from her home in Iqaluit. “Otherwise, we might see ourselves becoming like the Métis in [the Canadian province of] Manitoba, which was created with the idea of Métis nationhood, and there’s little or no evidence of that now.”

Others are looking for ways to build Inuit strength through cultural revitalisation.

Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory was one of the organisers of Idle No More, the indigenous social movement that swept across Canada last December. She said demonstrations in Iqaluit showed that Inuit had “had enough of living under colonial institutions”.

“People have to keep expressing that upwelling of will,” Bathory told Al Jazeera. “Finding ways of expressing oneself creatively is fundamental, and food sharing is a big part of both physical and mental health … It’s about taking cultural skills like hunting and cooperation and using those to create things like daycares, youth organisations and political parties.”