Renewed Nepali trade route draws regional ire

Sino-Nepali trade has grown 75 per cent in the past three years, worrying regional neighbours.

Kathmandu, Nepal – Trade between China and Nepal has soared 75 per cent in the past three years alone. This comes at the tail-end of a flurry of road reconstruction, along a thousand-year-old trade route between Kathmandu and Lhasa. But Chinese investment in Nepal’s transport infrastructure ruffles feathers in India, Nepal’s southern neighbour, where strategists are wary of China’s growing influence across the continent.

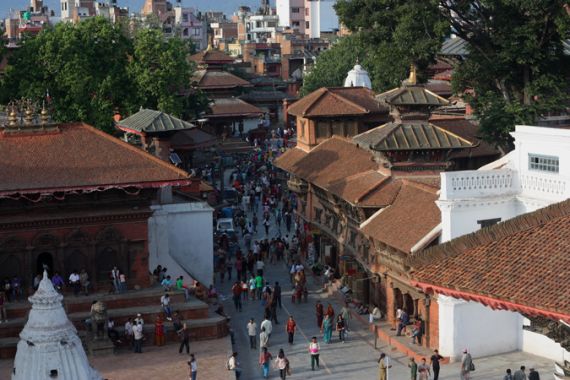

The cobblestone trail past the Maru Satah caravanserai in Kathmandu’s Durbar Square hardly looks like a strategic spot for beggars, let alone being of geopolitical importance to nation states. Two well-greased stone statues front the dingy wooden gazebo.

But to 78-year-old Soongma Tuladar, the old hostelry is the symbol of centuries of Himalayan commerce. This was the traditional meeting point for Indian and Tibetan traders in a caravan trade dominated by his Tuladar ancestors. As a teenager, Soongma himself saddled up his yak for the 26-day trek from Kalimpong to Lhasa.

Anything could happen en route: bandits, avalanches, landslides, hailstorms. They could travel for days without meeting another soul.

But once arrived in Lhasa, the young Soongma enjoyed a freedom unavailable to a young man of his Newari trader caste in the rigid social strictures of Nepal. “We could eat what we wanted, sit with anyone,” he recalled wistfully. Life in Tibet was so sweet that more than 500 Newaris settled in Lhasa until 1959 – when the Chinese invaded.

Then in 1962, India sealed its border after Chinese troops marched across the northeastern state of Arunachal Pradesh. Soongma’s old run from Kalimpong to Lhasa was blocked.

And the new Chinese bureaucracy was so unpleasant, most remaining Newari traders closed shop and took the one-way route home back to Maru Satah.

China is too different for Nepal to ever truly feel comfortable with in a close embrace... India is far more familiar and similar.

The closure did not last long. By 1966, in a show of friendship, China bankrolled a repaving of 116 kilometres of the old Nepali caravan route to the Tibetan border town of Khasa. And, within the past decade, Beijing has rapidly upgraded the track on its own side of the border, with blacktop running all the way to Lhasa and plans for a rail line up to Shigatse, a plateau town within 300 kilometres of Nepal.

Long-term ambitions

These initiatives are part of China’s larger push for economic engagement in South Asia, and it raises questions for Indian policymakers wary of China’s long-term ambitions: Is China extending its reach only to find new markets? Or are there more ominous geostrategic connotations for the recent binge of road building?

No such apprehension beset the Lhasa-Kathmandu caravan trade at its outset, back in the 7th century, when Nepali Princess Brikruti married the Tibetan king. The newlywed brought a train of artisans with her to Lhasa. The painters and woodworkers returned with tales of a people keen to barter gold dust and wool for utensils and textiles.

Back then, the trade balance was heavily in Nepal’s favour. The Newaris sold sacred statues, watches and bolts of cloth, Kamal Ratna Tuladar recounts in his detailed biography, Caravan to Lhasa. Meanwhile, Tibetans shopped in raw gold. Later, the government even sent silver bullion off the plateau by mule-back in exchange for Kathmandu-minted coins, an Old World version of a current account deficit.

Trade growth

But now the balance is tipped heavily the other way. Sino-Nepali trade is on the rebound, having grown 75 per cent between 2009 and 2012, albeit from a modest base of just $442m. Nepali exports barely account for one per cent of the country’s bilateral trade with China. Overland links have so far made little difference in the trade volume or balance, as almost all goods arrive by ship.

Around the corner from the Maru Satah, Tuladar’s cousin Ravindra runs a back alley wholesale shop selling everything from plastic bowls to aluminum wind chimes, all stamped “Made in China”. Once a year, he voyages to Guangzhou to order up new stock, which arrives in shipped containers in the Indian port town of Kolkata.

All this could change, however, according to Pancharatna Sakya, vice-president of the Nepal-China Chamber of Commerce. He envisions Nepal as a hub for China’s trade with the rest of South Asia.

|

However, to become a commercial nucleus, Nepal needs better infrastructure. The Chinese already funded a high-mountain container facility at Tatopani and pledged $190m to a 44.5 sq km cross-border free trade zone at Gyirong. On the Tibet side of the border, as part of their five-year-plan for the region launched in 2011, China has tarmacked 5,000 new kilometres of road.

In 2011, Chinese officials also announced that they were considering laying train track all the way to the border at Khasa. If it were up to officials from Nepal, the railroad would not stop at the border. Then-Nepalese Foreign Minister Narayan Kaji Shrestha suggested China extend the line across Nepal to Lumbini, the birthplace of Buddha on the Indo-Nepal border. This would certainly cause tension south of the border in India.

India ‘on its toes’

India is already on its toes after a suspected Chinese border incursion in Kashmir in April. China’s proactive role in building Nepal’s transport infrastructure could be seen as part of its ground game to challenge Indian dominance in South Asia. The two regional giants still dispute territorial claims in areas on either side of Nepal.

Nepal’s former prime minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal responded to these worries at a recent talk in New Delhi, saying that anything that spurred economic growth in Nepal “in the long run would contribute to ensuring and addressing the security concerns of India and China”.

India’s concern about China gaining an upper hand in Nepal is unwarranted, said one China-watcher in Delhi. Jabin Jacob, assistant director at the Institute of Chinese Studies maintains that India will have to adjust its geopolitical outlook, given that China has become Nepal’s largest foreign investor. However, he said, in the long term, Nepalis will likely never work too closely with their northern neighbour.

“China is too different for Nepal to ever truly feel comfortable with in a close embrace,” he said. “India is far more familiar and similar.”

But similarity was precisely the last thing Soongma Tuladar was looking for back in his entrepreneurial youth. The whole charm of his caravan life was the dissimilarity of the worlds he encountered. “Getting out of Katmandu was the good part,” he said. “Lhasa was so different from any other city.”

Meanwhile, the lure of these restored caravan routes awaits both the next generation of adventurous Nepali traders and the region’s most influential power brokers alike.