How Sudan muzzles its media

Politicians in both the north and south are running intimidation campaigns against journalists ahead of referendum.

|

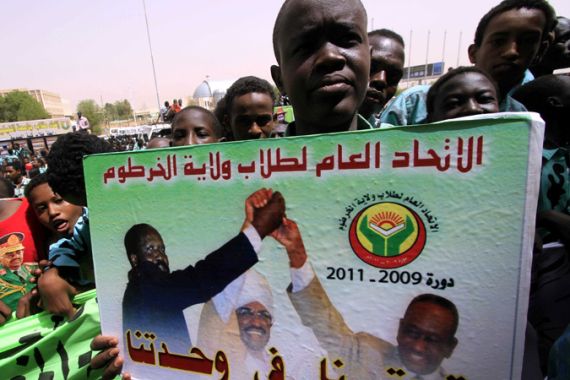

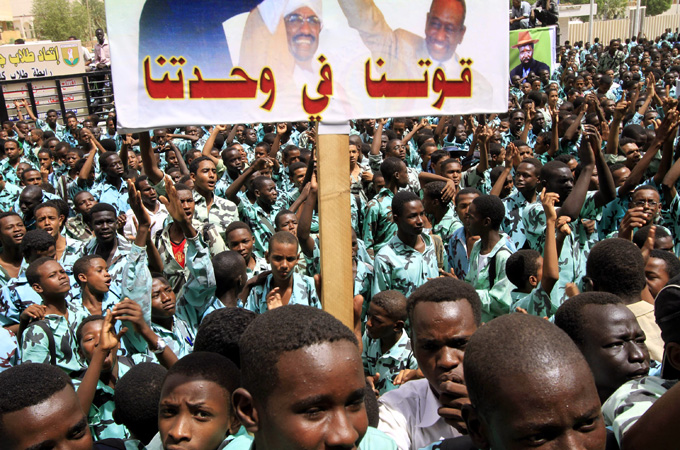

| Sudan’s future is at stake in January’s referendum, but Amnesty says journalists are not allowed to report freely [EPA] |

Friday’s special UN summit on Sudan, held three months ahead of a referendum on independence for the self-governed south of the country, is likely dominate news reports in the African nation. But as Sudanese journalists report the details of the meeting, they will have to be very careful of what they say.

Authorities in Sudan have been accused of a campaign of harrassment and intimidation against the media aimed at avoiding dissenting coverage, and as political tensions rise over the possible secession of the south, rights groups are warning that an already muzzled media could be slapped with further reporting restrictions.

“In every period of political turmoil in Sudan, the security situation has deteriorated,” Rania Rajji, Amnesty International’s Sudan researcher told Al Jazeera. “The referendum will be a very big issue for the future of the country and it’s likely that the space that is needed for debate and freedom of expression around the issue will be impacted by the security services.”

Censorship

Political interference in the freedom of the press is nothing new in Sudan, where the government ended its most recent period of pre-publication censorship in August of this year. Prior to that, agents from the National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS) would visit newspaper printing houses on a daily basis to ensure that critical articles were not published.

Some newspapers with a history of opposition to the ruling National Congress Party were closed down, and others were forced to suspend publication after NISS agents removed articles from their print editions.

The Sudanese government collects personal information about journalists, including their home address and bank details, and in September last year, a “code of journalistic honour” was introduced which effectively compels journalists to practice self-censorship or face legal reprisals.

When he announced the introduction of the code, Omar al Bashir, Sudan’s president, called for journalists to avoid covering subjects that are “destructive to the nation, sovereignty, security, values and its morality”. Journalists who trangress the code face arrest and abuse at the hands of the security services.

Reporting on political issues has become particularly difficult since this year’s presidential and legislative elections in April, with journalists facing major harassment for publishing articles criticial of al-Bashir’s government. In May, five journalists from the opposition-affiliated newspaper Rai al Shaab were arrested for publishing what the government described as “false news.”

Four of the journalists were tried. One was acquitted, but the other three were given custodial sentences of up to five years. At least two have said they were tortured in custody. The newspaper was closed down at the time of the arrests, and in July, a court order was obtained to prevent it from being reopened.

Other taboo issues for reporters include the proceedings of the International Criminal Court, which has issued an arrest warrant for al-Bashir over war crimes, public sector strikes and the prosecution of the Rai al Shaab journalists.

Amnesty International says that for journalists in Khartoum, the Sudanese capital, it has become “nearly impossible” to publish articles about human rights in newspapers because of the restrictions they face.

Despite south Sudan’s de facto autonomy, journalists working there fare little better. During the April elections, Amnesty said that journalists were harassed for criticising the south Sudanese government.

Amnesty fears that with the referendum approaching, the press may be compelled to shun pro-unity voices as the south’s government pushes for independence.

Even international broadcasters are subject to Sudan’s media crackdown. BBC’s Arabic radio service was taken off the air in four Sudanese cities including Khartoum in August after officials decided it had breached the terms of its broadcast agreement.

As Sudan moves into a period of potential political upheaval surrounding the referendum, Amnesty says that these reporting restrictions are robbing ordinary Sudanese of the opportunity to engage in a meaningful debate about the future of their country.

“The whole future of the nation will be at stake so there is the need for the whole of the country to take part in a debate over this,” Rajji says. “People need to be informed. The people are deciding not only the future of Sudan, but also for the future of their own lives.”