Changing tack on Myanmar

Why the US has switched policy to engage with ruling generals.

|

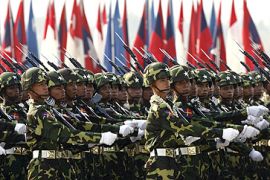

| Myanmar has been under military rule since 1962 [EPA] |

Barack Obama’s recent sortie into Asia has marked a radical change in Washington’s approach to the region, as the US president looks to re-engage after eight years of diffidence shown by the previous Bush administration.

Nowhere is the new US approach starker than its shift in policy towards military-ruled Myanmar, formerly known as Burma.

In recent weeks the US has begun to talk directly with the country’s ruling generals, who have been shunned by previous administrations.

There have been a series of meetings between senior US diplomats and Myanmar officials – in Naypyidaw the new Burmese capital, New York at the United Nations, and elsewhere.

It is a significant change of direction and one that is likely to increase competition for influence in the region between Washington and Beijing.

Critical move

The most critical series of meetings came during an early November visit to Myanmar by US Assistant Secretary of State Kurt Campbell.

Many expect him to make a follow-up visit before the end of the year.

|

“The ball is now very much in the Burmese court. Obama’s hand has been extended – will they respond in kind or with the clenched fist?” Sean Turnell, Macquarie University, Australia |

He told members of the National League for Democracy (NLD) led by the detained opposition leader, Aung San Suu Kyi that he would back in Myanmar very soon.

So far there are no real signs that this is going to happen, and western diplomats in Yangon are sceptical that a return visit is on the cards in the near future.

The main problem, it seems, is that Myanmar’s top military leader appears to have cooled on the idea of rapprochement with Washington.

“The ball is now very much in the Burmese court,” said Sean Turnell a Myanmar expert at Australia’s Macquarie University.

“Obama’s hand has been extended – will they respond in kind or with the clenched fist?” he told Al Jazeera.

Washington, for its part, has made its position clear: previous US policy, which relied almost exclusively on sanctions and isolating the regime, has failed miserably.

New approach

And so, earlier this year, secretary of state Hillary Clinton announced it was time for a new approach – one where sanctions were maintained, but supplemented by a dialogue with Myanmar’s military leaders.

“The US policy shift is part of Obama’s overall approach to foreign policy – he is doing the same with Pyongyang, Damascus, Havana and Tehran,” says Myanmar specialist, Derek Tonkin, a former British ambassador.

|

| Kurt Campbell, left, was the most senior US official to meet Aung San Suu Kyi [AFP] |

In contrast to Bush’s “unilateralism”, he says, it is a policy likely to produce better results.

The change in direction also comes amid a growing feeling on Capitol Hill that China has stolen the march on the US, creating a situation that is neither in the interests of Washington, or the region.

Democratic Senator Jim Webb, whose personal visit to Myanmar in August broke the ice with the top generals in Myanmar, is certainly convinced that this is the most important incentive for the US to re-engage, especially with Myanmar.

Many analysts in the region also welcome the shift in US policy and understand that, stated or otherwise, it will lead to a competition for influence with the Chinese.

“The US realises that if they are to retain American influence in this region, they must be able to match what China is doing,” Kishore Mahbubani, dean of the National University of Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy told Al Jazeera.

“If China is improving its ties by leaps and bounds… it is not in America’s interest to be left behind.”

Chinese presence

Historian Thant Myint-U, author of ‘A River of Lost Footsteps’, a history or modern Myanmar, agrees.

“China has had a free run in Burma [Myanmar] for nearly two decades, and will certainly be uneasy with the prospects of a rapprochement between Washington and the Burmese,” he says.

At the same time there are also signs that the overwhelming presence of the Chinese has also pushed Myanmar’s military to at least become more receptive to the US overtures.

The generals have become over-reliant on Beijing – especially for arms, military hardware and economic investment.

According to official figures, more than 90 per cent of direct foreign investment in Myanmar last year was Chinese, jumping more than a quarter over the past 12 months to more than $1bn.

The bulk of that investment was in the mining sector, oil industry and numerous hydro-electric schemes in Myanmar.

“I think China’s dominance of Burma, economically and politically, has reached its high tide,” says Sean Turnell of Maquarie university. “I think they are worried, and are right to be worried.”

“I’m really struck by what I can only describe as the seething resentment in Burma as to China’s dominance of the country’s economy, especially in resource extraction, but also in the various infrastructure projects — the influx of Chinese workers to build them — and in the massive influx of Chinese consumer goods.”

Myanmar polls

But while the regime may appear to be courting Washington’s recent advances, there is little evidence that the general’s plans for next year’s elections are going to be affected.

|

| Observers say Than Shwe may not feel the need to make any concessions [Reuters] |

The US diplomats team that went to Myanmar has made it clear what they are offering in return for improved bilateral relations.

“The [forthcoming] elections in Burma could be an opportunity for the country to end its international isolation, but only if these elections are inclusive, with the full participation of all political parties,” deputy assistant US secretary of state Scot Marciel told a press conference in Bangkok, following his visit.

“That includes creating the conditions in the run up to the elections which make the process credible.”

“There cannot be a credible election that has legitimacy without a thoroughly inclusive political process, and that cannot happen without dialogue,” he stressed.

So far there are few signs that the junta is seriously considering starting a dialogue with detained opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi, let alone releasing her.

There have been some tentative gestures, including allowing the Nobel peace laureate to talk directly with a government representative, the labour and liaison minister Aung Kyi, and meet various diplomats in Yangon, including Kurt Campbell and Scot Marciel.

Now Aung San Suu Kyi has written again to General Than Shwe asking for a meeting to discuss ways she could help the government ease its international isolation – a request which has so far been declined.

“This shows she has changed and is prepared to be flexible and compromise,” says Justin Wintle, the British writer who wrote the recent biography of Aung San Suu Kyi, ‘Perfect Hostage’.

But the problem is that the regime leader, Than Shwe does not appear to be inclined to accept her offer, or even talk to her.

“Than Shwe may feel there is no need to make any concessions, unless he wants to please the Americans,” says former ambassador Derek Tonkin.

“And it could now be only six months to the elections,” he warned.

Time then is running out for the US and the international community to influence events in Myanmar before next year’s vote.

‘No Asean leverage’

Both China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) have also urged the junta to make sure the elections are credible.

But both will likely wait and see rather than increase pressure on the regime in the lead up to the polls.

|

| Asean has called Myanmar to improve its human rights but has no special leverage [EPA] |

China prefers quiet behind-the-scenes diplomacy and is not likely to push very hard, fearing that they would be ignored if they were to do so, reducing any influence they do have and endangering their already large investment in Myanmar.

Asean on the other hand has made some noises in the past 12 months, especially under Thailand’s chairmanship of the regional grouping, emphasising the need for an inclusive and credible election.

But this also is unlikely to have much impact on the junta.

“There’s not much Asean can do,” historian Thant Myint-U told Al Jazeera. “They certainly have no special leverage.”

In recent weeks Myanmar government ministers and officials, including the prime minister Thein Sein, have hinted that Aung San Suu Kyi may be released before the elections.

But that in itself would not placate the US administration nor satisfy the international community.

Only her uninhibited participation in the elections would satisfy them and Senior General Than Shwe, Myanmar’s reclusive top leader, is highly unlikely to allow that.