Politics divide Kosovo’s schools

Serbian schools forced out of Pristina after 1999 see little hope of return.

|

| A classroom in one of the four schools under one roof in Mitrovica |

Maya, a student of English language at the University of Pristina, has been troubled by divisive political events in Kosovo which have been played out in the region’s education system.

She says she is “emotionally confused” because her university is no longer located in its namesake city.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘We share with rats’: Neglect, empty promises for S African hostel-dwellers

Thirty years waiting for a house: South Africa’s ‘backyard’ dwellers

Photos: Malnutrition threatens future Afghan generations

Founded in 1969 in what was then Yugoslavia, the university regularly played host to a battle between Kosovan nationalism and central administrative control from Belgrade, the Serbian capital. Throughout the 1990s, as Serb nationalism swept the region, Kosovan teachers and administrators were fired, and in some cases, imprisoned.

The Kosovan staff returned to the University of Pristina following a Nato bombing campaign to push Serb forces out of Kosovo in 1999. Eventually ethnic and political tensions led to the university being split in two.

The University of Pristina, located in Mitrovica in northern Kosovo since September 1999, is backed by the Belgrade government and instruction is in the Serbian language. However, the United Nations Mission in Kosovo (Unmik) recognises the institution only as the University of Mitrovica.

Meanwhile, the Pristina-based University of Pristina in newly-declared independent Kosovo offers courses in Albanian language with diplomas recognised by US and EU institutions.

Common ground missing

|

| Maya, middle, goes to the Mitrovica premises of the University of Pristina |

A 2005 report by the EU’s security and co-operation organisation, OECD, criticised both Kosovan and Serb administrators for a lack of “genuine tolerance or attempts to find a common ground between the Kosovo Albanian and Kosovo Serb communities regarding the consolidation of their educational system”.

The ongoing dispute over the fate of Serbia’s education system in Kosovo runs parallel to the greater debate over the future of the province itself.

As Kosovo’s new constitution comes into force, the territory will now have the power to determine whether to push on with an Albanian curriculum across the territory, despite Belgrade’s opposition, and whether those schools, teaching a Serbian curriculum, forced out of Kosovo in 1999, can rightfully return.

Predrag Stojcetovic, head of the Serbian Ministry of Education’s Section for northern Kosovo, said some 200 schools that left the territory in 1999 are now faced with huge problems every day.

“We don’t have enough room. Serbian schools from the southern part of Mitrovica moved to the northern part,” he said, referring to the northern Serbian-majority part of Kosovo.

“We have one school here that is actually four schools under one roof. In another building, a primary school, we have six schools under one roof, from the southern parts of Kosovo.”

With more power granted to Kosovo’s authorities on Sunday, Stojcetovic said he would like to discuss the right of return for those schools back to southern Kosovo, “because they have been evicted”.

“This is the only way the problem of Kosovo can be solved – by the repatriation of Serbs to the south and Albanians to the north of Kosovo,” he told Al Jazeera.

Returning home

Milynika Milosavljevic, head teacher for the high school for general education – one of the four schools under one roof in northern Mitrovica – said her school was bombed in 1999, and then became one of many “internally displaced schools”.

“We were one of the best schools in the city – we had great facilities, modern equipment and space.”

“In 1999, the school was not safe. While the bombing lasted, teachers risked their lives in order to go to school,” she said.

|

| Serbs say the Albanian curriculum leans heavily on nationalistic emotions |

On June 12, 1999, when Nato’s Kosovo force, Kfor, entered Kosovo forcing Serb forces out, Milosavljevic said, “Albanians started to do many nasty things, and we were not safe anymore”.

“Schools became scattered around the entire country [Serbia]. We came here, to Mitrovica. The doors of our school [in southern Kosovo] were locked, and I knew it was never going to be possible to return back to the school.

However, she holds on to the hope that one day both students and teachers will be able to return to the original premises.

She does acknowledge a sense of despair and betrayal, realising that the shools they left behind are now used as Albanian schools.

“The Serbian ministry of education financed the building of that school. It is our home. How would you feel if someone took away your home? A home that generations and generations had invested in.”

Curriculum switch

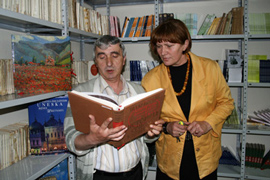

Dragoljub Kragovic, head teacher for the high school for economy – a second school of four under the same roof in Mitrovica – said before 1990, Serbs and Albanians went to the same schools and studied under the same curriculum.

However, during the 1990s, and after 1999, Albanians applied the curriculum for the “so-called government of Kosovo”.

“In certain subjects – history and literature – the Albanian curriculum was more nationalistic. It was a great surprise for us that they organised a parallel system that nobody recognised.”

“Their schools were organised in homes before we were driven out in 1999, without the adequate number of certified teachers, so they couldn’t even issue adequate diplomas,” he added.

Kragovic rejects the premise of an independent Kosovo with its own administration and scholastic system. He refers to Kosovo as part of Serbia in which the curriculum will always be based on the education system in Belgrade.

Educating Mitrovica

|

| Kragovic, right, said before 1990, Serbs and Albanians went to the same schools |

But the emphasis on maintaining a Serbian curriculum in Kosovo goes beyond mere differences in methodologies; it highlights Belgrade’s social and psychological claim to Kosob.

Stojcetovic said that keeping as much of the Serbian curriculum in Kosovo – taught in 103 schools in Kosovo’s Serbian enclaves – gives Serbs a important reason to stay in the territory.

“Attempts had been made to incorporate the education system of Kosovo Albania into the Serbian curriculum in Kosovo, but something official like this would just speed up the eviction of Serbs from Kosovo,” he said.

“With a Serbian system still in place in Kosovo, it keeps people from migrating out of the territory into central Serbia.”

But Bajram Rexhepi, Kosovo’s mayor of Mitrovica, referred to the February declaration of independence and said that the north of the city would “never go to Serbia.”

“It is not acceptable; it is not possible under our jurisdiction anymore,” he said.