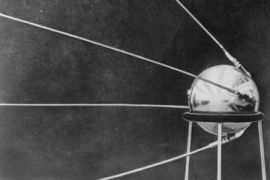

When Earth got another moon

Sputnik’s launch acted as the starting pistol in the Cold War space race.

|

| Sputnik beeped for three weeks and spent about three months in orbit before burning up in the atmosphere EPA] |

The time: October 4, 1957. The place: The arid steppes of the Soviet Republic of Kazakhstan.

The event: A rocket designed to deliver nuclear bombs blasts off with an unusual payload – a sputnik, Russian for satellite.

Minutes later, the satellite sends back what would be the world’s most famous beep. And Earth, after having one moon for a billion years, suddenly had another – an artificial moon.

Like many a turning point in the history of civilisation, even the people behind the event did not immediately grasp its importance. They saw the Sputnik’s launch as simply one in a series of Soviet technological achievements, like a new passenger jet or the first atomic-power plant.

| In Video |

The first official Soviet report of Sputnik’s launch was brief and buried deep in Pravda, the communist party daily.

Two or three days later, once the world’s media had run amok with the news, did Pravda realise the significance of the event and offered a banner headline.

The New York Times was quicker: “Soviet fires earth satellite into space; it is circling the globe at 18,000mph; sphere tracked in 4 crossings over US,” said a two-line headline splashed across the front page on October 5, 1957.

“Actually getting the spacecraft into orbit was a fantastic feat. To actually have the rocketry to be able accelerate Sputnik to 17,500 miles an hour, which is the escapement speed you need to get away into Earth orbit,” said Andrew Coates of Mullard Space Science Laboratory, University College London.

But the news did not seem to go down well with the US establishment.

Space race begins

“We knew the Russians were good at ballet and vodka production, but we thought that they were behind us technologically,” said Simon Ramo, 94, one of the architects of America’s Intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) programme during a recent conference to mark the 50th anniversary of space exploration.

Dwight Eisenhower, then the US president, famously dismissed it, saying: “One small ball in the air.”

| The simplest satellite |

|

When the warhead project hit a snag, Sergei Korolyov, the father of the Soviet space programme, pressed the Kremlin to let him launch a satellite. The US had its own programme called Vanguard, he pointed out, and was planning a launch in 1958 as part of the International Geophysical Year. The Soviet Union already had a full-fledged scientific satellite in development, but it would take too long to complete. So Korolyov ordered his team to quickly sketch a primitive orbiter. It was called PS-1, for “Prosteishiy Sputnik” – the Simplest Satellite. The satellite, weighing just 83.5kg, was built in less than three months. The pressurised sphere of polished aluminum alloy carried two radio transmitters and four antennas. An earlier satellite project envisaged a cone shape, but Korolyov preferred the sphere as “the Earth is a sphere, and its first satellite also must have a spherical shape”. Sputnik beeped for three weeks and spent about three months in orbit before burning up in the atmosphere. It circled Earth more than 1,400 times, at just under 100 minutes an orbit. The tiny orbiter was invisible to the naked eye. But what was that winking light that crowds around the globe gathered to watch in the night sky? Not Sputnik at all but just the second stage of its booster rocket, which was in roughly the same orbit. |

But while publicly playing down the significance of the launch, he was more animated privately. Within days Eisenhower held a secret summit with US scientists. And his message was clear: win the space race.

Overnight, the study of science got a boost in the US: a presidential adviser for sciences was appointed, and in July 1958 Nasa was created.

“No event since Pearl Harbour set off such repercussions in public life,” writes Walter McDougall, a historian at the University of Pennsylvania.

Edward Teller, father of the US hydrogen bomb, went a step further, to say: “A greater defeat for our country than Pearl Harbour.”

With Sputnik’s launch, the Cold War “became total, a competition for the loyalty and trust of all peoples fought out in all arenas of social achievement, in which science textbooks and racial harmony were as much tools of foreign policy as missiles and spies”, McDougall says in his book The Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age.

Yet despite the efforts to catch up, the US appeared to lag behind in the early years of the race.

By the time the first US satellite was launched on January 31, 1958, after a series of embarrassing failures or “flopniks” as some headlines put it, the Soviet Union had already placed the first living creature from Earth into orbit. Laika, a mongrel dog, was sent into space in November 1957.

The Soviet Union continued to set the pace, becoming the first country to land an object on the Moon in September 1959, and only two years later, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space, in April 1961.

Eisenhower’s successor, John F Kennedy, thus set out the US objective to land the first man on Moon.

“I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him back safely to the earth,” Kennedy declared.

“No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

Losing the lead

The US began pouring billions of dollars annually into its space programme.

Payday came on July 20, 1969, when Neil Armstrong stepped onto the Moon’s surface in one of the defining moments of the 20th century.

The success of the lunar landings put the US ahead of the Soviets in space and wiped away early humiliation.

Some in the West saw the Soviet achievements as a threat. They warned of the need for “a psychological adjustment” not only towards the Soviet Union but towards its military capabilities.

“I say without hesitation and without excuse that this is a turning point in history. Never has the threat of Soviet communism been so great, or the need for countries to organise themselves against it,” said Harold Macmillan, the then British prime minister in the House of Commons in November 1957.

Lyndon Johnson, US senate majority leader (and later president), was more dramatic: “[The Soviets could one day be] dropping bombs on us from space like kids dropping rocks onto cars from freeway overpasses.”

But it was not all that sinister, at least in the early years.

The foray into space gave a psychological lift to Soviet society. It marked a break from life under Joseph Stalin, who had died in 1953, to a more optimistic and easier era promised by Nikita Khrushchev.

“Society itself was very upbeat in the 1950s…. Space was associated with going beyond limits. In this case it was physics but it could be associated with going beyond tradition,” said Boris Kagarlitsky, a writer on the period and director of the Moscow-based Institute of Globalisation.

“Although there was a military element in space projects … they were presented with a humanitarian aspect. The aspect of rivalry with the United States was not much evident in the beginning especially because the Soviets were leading.”