Ex-oil-food chief accused of corruption

Investigators probing claims of wrongdoing in the Iraq oil-for-food programme accused its former chief, Benon Sevan, of corruption for taking illegal kickbacks and recommended his immunity be lifted for prosecution.

The investigators also accused a former UN procurement official, Alexander Yakovlev, of collecting nearly $1 million in kickbacks outside the oil-for-food programme.

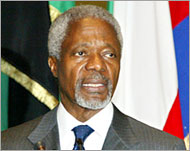

Later Monday, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan agreed to lift Yakovlev’s immunity after receiving a request from the US Attorney’s Office, Annan’s Chief of Staff Mark Malloch Brown said.

He said Yakovlev had apparently been taken into custody.

‘Significant and troubling’

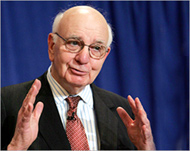

The third report by the Independent Inquiry Committee, led by former US Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker, was a new blow to the scandal-tainted programme worth $64 billion. For the first time, it gave a motive for Sevan’s actions, saying his finances were “precarious” shortly before his alleged misdeeds.

|

|

Volcker has called on Annan to |

“Our conclusions are obviously significant and troubling,” Volcker said at a news conference.

Some critics have accused the United Nations of squandering millions – and even billions – of dollars in its mismanagement of the programme. Yet Volcker’s team found that Sevan appeared to have gotten kickbacks of just $147,184 from December 1998 to January 2002.

The report touched briefly on Annan and his son, Kojo. It said new e-mails suggesting Annan knew more than he said about his son’s involvement in the programme “clearly raises further questions” that would be answered in its final report, expected in September.

Diplomatic immunity

Yakovlev resigned this year and Sevan announced his resignation on Sunday. He criticized investigators, Annan, the UN Security Council and the UN critics who have cited oil-for-food as emblematic of perceived UN bungling and outright corruption.

|

|

Annan’s son was involved with |

“As I predicted, a high-profile investigative body invested with absolute power would feel compelled to target someone, and that someone turned out to be me,” Sevan wrote. “The charges are false, and you, who have known me for all these years, should know that they are false.”

Though both men have quit, diplomatic immunity would cover their actions when they were employed. Volcker’s recommendation that Annan waive that immunity was a strong indication of his conviction about the claims against them.

“All I can fairly say is that given the kind of evidence that we have presented I would think there may well be interest in doing so,” Volcker said.

Humanitarian programme

Sevan, a Cypriot citizen believed to be in Nicosia, is being investigated by the Manhattan District Attorney’s office. There is no known criminal investigation against Yakovlev so far.

The oil-for-food program, launched in December 1996 to help ordinary Iraqis cope with UN sanctions imposed after Saddam Hussein’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait, was one of the largest humanitarian programs in history.

|

“The charges are false, and you, who have known me for all these years, should know that they are false” Benon Sevan, |

By most accounts, it achieved what it set out to do, becoming a lifeline for 90% of the country’s population of 26 million.

Under the programme, Saddam’s government could sell oil, provided the proceeds went to buy humanitarian goods or pay war reparations. Saddam allegedly sought to curry favour by giving former government officials, activists, journalists and others vouchers for Iraqi oil that could then be resold at a profit.

The programme has become the subject of several congressional investigations, as well as inquiries by a federal grand jury and the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Boutros-Ghali relative

On Thursday, Sevan’s lawyer Eric Lewis had revealed that the committee concluded that Sevan got kickbacks for steering contracts under oil-for-food to a small trading company called African Middle East Petroleum Co. Ltd. Inc.

The report largely confirmed that, but went further. It described how he and his wife had repeatedly overdrawn their bank accounts before Sevan first sought to steer oil allocations to AMEP.

It found that two men helped Sevan: Fred Nadler, an AMEP director and brother-in-law of former UN secretary-general Boutros Boutros-Ghali; and Fakhry Abdelnour, the president of AMEP.

Volcker’s team recommended that the United Nations assist in their possible prosecution as well. As for Yakovlev, investigators also found that he secretly tried to bribe a company called Societe Generale de Surveillance S.A., which was seeking an oil inspection contract under oil-for-food.

Bribes

They said Yakovlev passed secret bidding information along to a friend in France, Yves Pintore, who then approached SGS to check if it would “work with” him and “influential people in the UN in New York”.

Volcker’s team found no evidence that the company agreed to the bribe. However, it noted that Pintore essentially agreed to its characterization of his involvement.

The committee found “persuasive evidence” that Yakovlev took kickbacks outside oil-for-food from other companies that had won some $79 million in UN contracts.

It said it had found that some $1.3 million had been wired to a bank account in Antigua, West Indies in the name of Moxyco Ltd. Of that, more than $950,000 had been traced to those companies so far.