Tibet: A thorn in China’s flesh?

They came in their thousands to hear him; monks from nearby monasteries and from far away countries; sitting on flagstones outside the two-storied temple; with prayer beads in their hands.

There were dozens of Western backpackers, too. All curious to catch a brief glimpse of who they perceive to be the ‘reincarnated’ Buddha, the Dalai Lama.

Although many in the crowd find his lecture esoteric – some of them dozed off under the midday sun – there is a small group that recently arrived from Beijing to listen to him in all earnest.

“It is for us an amazing opportunity…we study Buddhism, because life in China is so lacking in spirituality,” says their leader, who asked not to be identified.

Though, under no threat of repercussion for their visit to the Tibetan government in exile’s current home in the mountains of northern India, their pilgrimage is none the less symbolic, given that the Dalai Lama is still persona non grata in a country he last saw in 1959.

|

|

Tibet is always known in the West |

Dubbed a ‘splittist’ by the Chinese government for his earlier insistence that Tibet is an independent country, the Tibetan spiritual leader has often expressed a desire to once more visit his homeland. That wish may still be granted.

Since 2002, a series of annual talks between Beijing and Dharmsala – the north Indian hill town that has been the home of the Dalai Lama since the 1960’s – have been held in an unprecedented attempt to resolve the long-standing issue of Tibet’s status, the most recent being in early July. Tibetan officials say they are cautiously optimistic of a breakthrough.

Likened to the mystical ‘Shangri-La’, Tibet has long held fascination for the West. Evocative of impregnable mountain passes, forbidden cities and a deeply ingrained spirituality, this overly romanticized image was shattered when soldiers of the newly formed People’s Republic of China invaded, or as the Chinese put it, ‘peacefully liberated’ the country in 1951.

In official Chinese propaganda, however, Tibet of pre-1950 had few redeeming qualities. Described as a ‘feudal’ backwater at the mercy of ‘foreign imperialist and expansionist forces’, in Marxist eyes, Tibet was crying out for help.

And while Tibetans say they have always been a separate nation, Beijing says that the two have been part of the ‘big Chinese family’ since the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368).

Though predictions of a Communist Party collapse and possible fragmentation of the country remain favourite topics of China- watchers, and give hope to Tibetan activists in the long run, in the short to medium term, officials are talking of a growing crisis to preserve what’s left of their culture.

Middle way

|

|

China claims to have ‘liberated’ |

Massive immigration from other parts of China has diluted indigenous customs and language. Already, say officials, Han Chinese outnumber Tibetans several times over. In response, the Tibetan community has adopted a negotiating stance, known as the ‘middle way’, in the hope of initiating dialogue. In effect an articulation of the Dalai Lama’s position since the late 1980’s, it eschews calling for complete independence, and, instead, asks for limited autonomy in the form of an elected parliament and control over all policy issues except defence and foreign affairs.

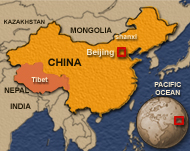

Unprecedented in any of China’s 31 provinces, these demands are further complicated by the fact that the Tibet, the government in Dharmsala refers to, and the Tibet that appears on contemporary world maps, are no longer the same. One third the size of its former self, much of the country and its population, have been divided up by neighbouring Chinese provinces.

“The ‘middle way’ approach is not something that has been imposed. It has been legislatively sanctioned by the Tibetan parliament, so the parliament has passed a resolution saying it is the policy of the parliament and administration that we follow the ‘middle way’, says an emphatic Thupten Samphel, the Dharmsala government’s secretary for information.

A tiny, yet crowded, jamboree of guesthouses, government buildings and monastic centres, the earthquake-prone Dharmsala has been the home of the Tibetan government-in-exile since the early 1960’s. Given to His Holiness, as many here call him, after he fled Tibet following a failed uprising against Chinese rule, the government was then reformed along democratic lines. It is hoped that this model could be transferred to Tibet, depending upon how the talks proceed.

History of talks

Begun under the former government of Jiang Zemin, the exact content of the talks remain shrouded in secrecy.

“For many years, we viewed each other suspiciously as though we each had horns on our heads” |

“It has been very slow and time-consuming. The first two times, we had a preliminary dialogue and the third time we spoke in more detail, with both sides expressing their doubts and reservations,” explained Tibetan Prime Minister Professor Samdhong Rinpoche. At the most recent meeting, held in Switzerland, a press release put out by the Tibetan government said that, “despite the existing areas of disagreement…both sides had a positive assessment of the ongoing process.” Direct negotiations, however, have yet to start.

“For many years, we viewed each other suspiciously as though we each had horns on our heads. If the talks continue to grow, as they are now, then we could move to full blown negotiation. Being realistic we can’t expect suspicion to clear and the air made clean by one, two, three, four visits.

In a number of years, we will get to know each other, our positions and sensitivities, so that with full confidence we can resolve the issue of Tibet peacefully,” believes Samphel.

Though previous Chinese leaders have been quoted as saying that China can just wait until the Dalai Lama dies for the problem to resolve itself, that thinking appears to no longer be in vogue. Pursuing a policy of non-violence, the current Dalai Lama, the fourteenth since 1391, may, one day, be succeeded by a reincarnation that believes a more confrontational approach is needed, as some in Dharmsala currently advocate.

In addition, the issue of Tibet remains an embarrassment for a Chinese leadership keen to be fully accepted as a leading nation in the global community. Being able to reach a compromise with the Dharmsala government, which regularly lambasts Beijing for human rights abuses, would help accomplish this.

Autonomy

|

|

Muslim-majority Xinjiang province |

What exactly Beijing would be prepared to give, however, remains unclear. One possible concern is that by granting a degree of autonomy to Tibetans, other provinces with large non-Han Chinese populations may be encouraged to raise similar demands. To the north of Tibet, the nominally Muslim province of Xinjiang has already made headlines with sporadic outbreaks of violence including bus bombings, riots, and shootings with some there calling for a complete separation from China.

Another worry is that once granted autonomy, Tibetans will merely continue their calls for independence. If negotiations begin, Beijing will want to concede as little as possible to secure an agreement with the Dalai Lama.

Skeptical of Chinese intentions and against the compromised stance of the Dalai Lama, Lobsang Yeshi, vice-president of the Tibetan Youth Congress (TYC), the largest Non-Government Organisation (NGO) in Tibet, holds little faith in dialogue.

“Because of these facts China and Tibet cannot work out their differences through peaceful negotiation. We have seen in the history how faithful, how loyal, how sincere Chinese are,” says Yeshi sarcastically.

Dalai Lama’s successor

Listing changing demographics, human rights abuses, an education system that neglects traditional Tibetan culture and language, mineral exploitation, and use of Tibet as a nuclear waste dumping ground, the TYC advocates violence in solving Tibet’s problems.

|

“Today, Tibet’s situation has become very complex, very crucial. Something has to be done. We opt for violence as Tibetan people are in danger” |

“Today, Tibet’s situation has become very complex, very crucial. Something has to be done. We opt for violence as Tibetan people are in danger,” says Yeshi, though he stresses that his members would never contravene the Dalai Lama’s current stance on peaceful protest.

Representing 30,000 members of TYC, Yeshi evokes memories of past fighting against the Chinese, firstly in the failed uprising of 1959, and then with the aid of the CIA during the Cold War, in a longer running operation called ST CIRCUS in the 1950s and 60s that saw Tibetan operatives trained in Nepal and then smuggled into China.

For now, though, Dharmsala is committed to peace. While officials say this is the best hope so far for a negotiated settlement, there are signs that they remain skeptical of the chances for a breakthrough. Indicative of this has been the Dalai Lama himself. Celebrating his seventieth birthday on 6 July, he has already announced that search parties should look for his reincarnation amongst Tibetan communities outside of China, and so avoid possible Chinese interference.