A mother’s tragedy

Nabza Bano lost her three sons and her home to the conflict.

|

| Las Khan and Nabza Bano have lost all of their sons to the conflict [Majid Maqbool] |

Sixty-five-year-old Nabza Bano stands near a small cornfield where her three-storey house once stood in Sundbrari village, about 85kms from Srinagar, the capital of Indian-administered Kashmir. Lost in a melancholic silence, she points out all that remains of her old home – a few burnt logs.

She says two of her houses were burned down by the Indian army, along with two cowsheds, but what pains her most is the absence of her three sons – all of them killed by the Indian army. Their loss has inflicted a wound that only festers with the passing years.

But years of mourning have dried her tears and she is unable to weep now.

After their house was destroyed, Nabza and her family lived in a tent adjacent to the burnt remains of their home for six months during a harsh Kashmiri winter. The family’s neighbours and relatives helped them to build a modest one-storey house where Nabza now lives with her terminally-ill husband, her daughter, son-in-law, their two children and the two children of her now deceased eldest son.

They live in poverty. Nabza’s son-in-law works as a labourer, but he is the only wage earner in the family and his salary is not enough to support them all.

Nabza’s husband, Las Khan, suffers from asthma and his treatment costs about 15,000 Indian rupees ($340) a month. Last month, the family had to sell off one of their cows to cover the cost.

Picking up the gun

|

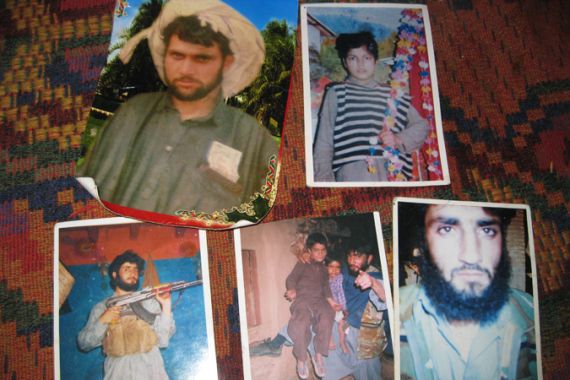

| Nabza displays pictures of her sons [Majid Maqbool] |

Las Khan has lost four sons to the conflict, including one from his first marriage. Mukhtar Ahmad was 40 when he was killed in an encounter with the Indian army in 1997. Khan says his eldest son was a militant.

The youngest of Khan’s sons with Nabza was just 13 years old when he was killed in 1999. Nabza says Mohammad Abbas would sometimes help out militants who were active in the area by showing them safe passages. “But he was not a militant and never had a gun. He was innocent,” she adds.

On the day he was killed, Nabza recalls, he had put on his best clothes and taken food for a few of the fighters who were in the mountains.

“As soon as they finished eating, the army laid an ambush and killed all of them in the encounter,” Nabza says. Seven were killed that day, including Mohammad. The death certificate issued by the police refers to Mohammad as a “19-year-old militant”.

Ajaz Khan and Ghulam Hassan – the elder two of Khan’s sons with Nabza – picked up the gun in the early 1990s when the armed struggle broke out in Kashmir. They both joined the indigenous rebel group, Hizbul Mujahideen.

Ajaz was 25 when he was killed in an encounter with the Indian army in 2002.

“He had come home that day after more than six months,” Nabza recalls.

But the army had laid an ambush outside their home and Ajaz was killed in the fighting that ensued. He was shot twice in the chest.

“Army from seven companies laid an ambush for him that day,” Nabza says. “Some families had offered him a safe house during the encounter but he declined, saying he could not bring harm to any civilians.”

Nabza says the shooting began at four o’clock in the afternoon and Ajaz fought until he ran out of ammunition. He was killed at around two o’clock in the morning. After his death, Nabza recalls, the soldiers fired shots into the night in jubilation.

Ghulam was one of the first young men from their village to join militant ranks in the early 1990s, Khan says.

“In 2003, he was arrested and tortured in custody for eight days in the RR [Rashtriya Rifles] military camp,” Nabza adds.

After he was released and returned home, Nabza says, her son bore the marks of torture on his body – his face was swollen, his kidneys damaged and he could barely walk or talk. A few days later he died.

“He died when he was offering morning prayers in this room,” Nabza says. “I held him close to my chest. I would not let him go,” she recalls. “Then I don’t know … I fainted.”

“After he died … the army lied and said that he had a heart attack in custody,” Khan interjects. “They even wrote this lie on his death certificate,” the old man explains.

Ghulam was the only one of their sons to marry. After he was killed, his wife remarried and Ghulam’s son and daughter came to live with Nabza and her husband.

‘Mother of militants’

|

Las Khan fell ill after the deaths of his sons and has been bedridden for the past 10 years. Photographs of his sons hang beside each other on the wall of his small room. He cannot speak or hear well, but he recalls the details of their deaths with clarity. He remembers the date and the deed. And even though illness has made him too weak to walk, he never misses a prayer. Gasping for breath, he prostrates himself in prayer five times a day.

Beside his bed is a small trunk. Nabza unlocks it and carefully removes pictures of their sons and their death certificates. She spreads them out on the floor, one by one, and stares at them. There are pictures of funeral processions, of people offering funeral prayers, others showing the burnt remains of their old home. She addresses the pictures as though talking to her sons in person – incoherent lamentations of how much she misses them and how she wishes that at least one of them had lived.

A child enters the room. He is the son of Ghulam. He carries a blackened samovar that had been found a few days before at the site of their old house. They gaze at it, turning it around. Their silence is filled with memories of their life before. Nabza explains that they used to serve tea to guests in this samovar. She says it was the only thing recovered from the burnt remains. Everything else was consumed by the fire.

Nabza recalls how in 1998, soldiers had raided their home, threatening to set fire to it. She says they had called her “the mother of militants”.

Las Khan produces a pocket diary. He flips its small pages, showing entries made in Urdu. It is a detailed record of the dates his sons were killed and his properties destroyed – a written testimony to the tragedies the family has endured.

When his sons were alive, Khan was himself arrested several times by the Indian army. He says he was tortured and beaten in custody for failing to convince his sons to surrender. His son-in-law shows an old mobile phone picture of Khan’s bandaged broken arm.

“The army said they would give me 1.3 million rupees if my son surrenders,” Khan explains. “But my son had not picked up the gun for money. He would not even call me father had I taken even 15 paisa from the army.”

Looking at her ailing husband, Nabza remembers how he was beaten every time their home was raided by soldiers looking for their sons. “I felt as if I was receiving those blows,” she says. “Those blows also hit my body.”

The family says the authorities told them that they could not claim any compensation for their houses or cowsheds because their sons were militants. Neither did they receive any substantial aid from groups opposed to Indian rule.

Now, all that Nabza is left with is her unshakable faith in God. She has a firm belief that her sons did not die in vain. “We will get freedom one day, God willing,” she says with conviction.

For Nabza, her sons remain alive in her memories. She talks to their pictures as though they are there with her. “All my sons are alive,” she says in Kashmiri, looking at the pictures spread out in front of her. And then, after a brief pauses, adds: “We are all dead.”