Who is poisoning Russian dissidents and why?

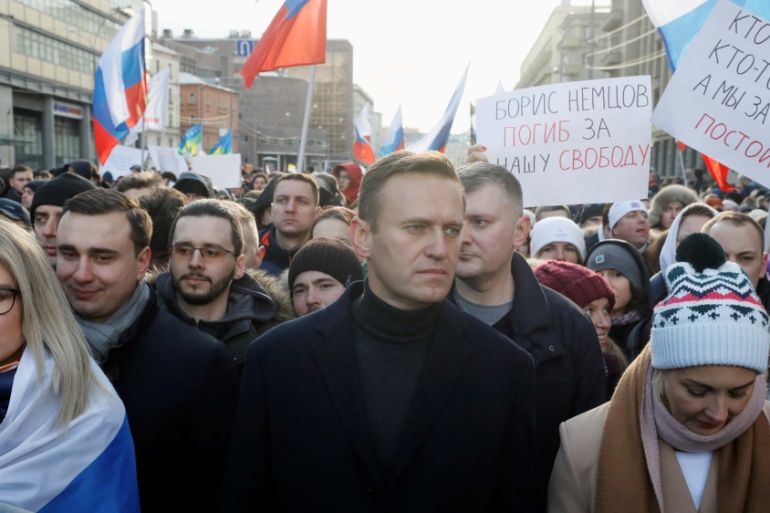

Alexey Navalny’s suspected poisoning follows a string of similar incidents with Russian government critics.

On Thursday morning, Russian opposition leader Alexey Navalny walked out of a hotel in the Siberian city of Tomsk and headed for the airport to catch a flight back to Moscow. His trip to the Tomsk region was part of his campaign to “nullify United Russia” by voting the party of Russian President Vladimir Putin out of power in the upcoming local elections.

At the airport, Navalny and a few members of his team had tea and boarded the plane. Shortly after takeoff, the 44-year-old politician started feeling unwell. He went to the lavatory and could not come out. The aeroplane was forced to do an emergency landing in Omsk. Fellow passengers heard Navalny screaming in excruciating pain before he was taken out of the plane by medical personnel. Shortly after he was hospitalised, he fell into a coma.

The intensive care ward where he was kept soon filled up with plain-clothes and uniformed security officers, who at some point seemed to outnumber the medical staff.

Doctors and policemen gave contradictory information; first, they claimed a dangerous chemical was discovered in Navalny’s blood, then that no such substance was detected. When Navalny’s wife Yulia and press secretary Kira Yarmysh demanded that he be flown abroad for treatment, citing the substandard conditions of the hospital where he was kept and its lack of equipment to provide proper care, medical staff refused, claiming that any such move would worsen his condition.

On Friday evening, after a number of Western leaders concerned about Navalny’s wellbeing phoned Putin, the hospital finally released him and he was flown to Germany for treatment.

Russian activist and founder of the media outlet Mediazona, Petr Verzilov said that all of this reminded him of what he went through when he was allegedly poisoned two years ago.

“Everything begins with a place which can be easily controlled, in the case of Navalny, this was the airport; in my case – the court,” he told me. On September 11, 2018, Verzilov spent the whole day in court, where his girlfriend Nika Nikulshina was being tried for running onto the pitch wearing a police uniform during the World Cup. At 6pm, they headed home, where Verzilov had a nap. A couple of hours later, when he tried to go out, he felt sick; his eyesight, speech and movement started deteriorating and he eventually slipped into delirium, unable to recognise his own girlfriend.

In the hospital, the same scene played out – a great number of security personnel preventing relatives and associates from seeing him. The Russian doctors also did not find any toxin in his blood and delayed his transfer abroad. He arrived in Germany for treatment on September 15. By then, his body is thought to have gotten rid of the poison, which made identifying it very difficult. German doctors hypothesised that hyoscine may have been used to poison Verzilov, as it is known to cause symptoms similar to those he displayed.

Another opposition politician, Vladimir Kara-Murza has also said the circumstances of Navalny’s illness reminded him of what he believes were two attempts to poison him.

The first time was in May 2015, shortly after opposition politician Boris Nemtsov was shot and killed just a few hundred metres from the walls of the Kremlin. Before his death, he and Kara-Murza had supported the application of the Magnitsky Act, a bill aimed to impose sanctions on members of Putin’s inner circle over human rights violations.

Kara-Murza survived, but doctors did not find a toxin in his blood and claimed he must have overdosed on anti-depressants – an idea rejected by independent medical professionals. Samples of his blood, hair and nails were sent to France, where experts found a high concentration of heavy metals.

The second attempt took place in 2017. Kara-Murza suffered similar symptoms as the first time – sudden deterioration of his health and multiple organ failure. It was a miracle he survived and again no toxin was found in his blood.

All of these cases seem similar to the suspected poisoning of famous journalist Anna Politkovskaya. In September 2004, while on her way to Beslan in North Ossetia, where terrorists had just taken hostage students and teachers at a local school, Politkovskaya fell suddenly sick after having tea and fell into a coma. She also survived but again, no poisonous substance was found. Two years later, she was shot dead.

Of course, there is also the poisoning of former double agent Sergey Skripal in the British city of Salisbury, with the nerve agent Novichok. Skripal and his daughter were found unconscious on a bench in the town centre. The British authorities later found traces of the chemical in his home and accused Russian military intelligence (GRU) agents of being responsible for the poisoning. Both Skripal and his daughter survived.

All of these cases have a lot in common – they seem to all involve a certain neurotoxin which gives the victim a chance to survive. They differ from other cases – such as ex-KGB agent Alexander Litvinenko’s poisoning with polonium in London in 2006 or that of journalist Yuri Shchekochikhin, who was also possibly killed with a radioactive substance in 2003 – where the chemical of choice ensures certain death.

Thus, it is possible that in Navalny’s case, like others similar to his, poisoning is meant to scare, not to kill. For Verzilov, that was a way to suggest to him that he needs to stop his investigation into the killing of three Russian journalists in the Central African Republic. For Kara-Murza – this was to tell him to stop lobbying for sanctions on people close to the Kremlin. For Skripal – not to cooperate with the British intelligence. For Politkovskaya – not to go to Beslan.

Navalny, like everyone else above, is a prominent critic of the Kremlin and the structures and people close to it. But he has been openly critical for a while and for a few years now has been mobilising political protests and conducting major investigations into high-level corruption, which have angered many in the Russian ruling elite.

So the question is, why send him a warning that he is no longer safe and should consider going abroad now? The answer is simple: Putin’s rating has fallen to an all-time low and his decision to change the constitution to potentially extend his term beyond 2024 stirred so much anger that only the coronavirus pandemic managed to stop it from spilling into the streets.

Still, even in the current epidemic conditions, protests have broken out in some places. In Khabarovsk region, demonstrations against the removal of a popular governor have been going on for more than a month now.

More importantly, in neighbouring Belarus, ordinary people have mounted a major campaign of civil disobedience against longtime President Alexander Lukashenko. They have protested the rigging of the presidential elections en masse, engaged in labour strikes, defected from state institutions, persevered in the face of police brutality and torture, etc.

The scenes of mass demonstrations in Belarus have evoked much sympathy among various layers of society in Russia: from the urban intelligentsia to factory workers and even football fans. Navalny’s trips across the country would have surely inflamed further anti-government sentiments.

Incapacitating Navalny could undermine the ability of dissenting Russians to organise, by depriving them of a charismatic leader. This could deescalate the situation and preclude mass protests, but it could also have the opposite effect. If the poisoning is proven, this could fuel further public anger and result in spontaneous mobilisation.

Nemtsov’s murder followed the first scenario. The outpouring of anger following his death was contained in mourning rallies. In the case of Navalny, however, the second scenario is quite likely.

In the past few years, a new generation has come of age which is more tech-savvy and more politicised than previous ones, and have repeatedly demonstrated that they do not fear the Kremlin’s repressive tactics.

Meanwhile, the Belarus example has shown that political mobilisation by far does not depend on one leader and can persist and grow even when opposition figures are imprisoned and forced into exile.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.