The Lebanese revolution must abolish the kafala system

Lebanese and foreign workers should be afforded a life of dignity in Lebanon.

On Tuesday, November 5, the 20th day of the ongoing uprising in Lebanon, an Ethiopian Airlines flight from Beirut arrived at Addis Ababa’s Bole International Airport. Its cargo was seven dead bodies of Ethiopian domestic workers who had died in Lebanon. According to Ethiopian journalist Zecharia Zelalem, “100s of family members, some from as far as Wolaita were at the airport in what became a mass mourning procession.”

Zelalem had previously published a long investigation into efforts by both the Lebanese and Ethiopian authorities to cover up Ethiopian deaths in Lebanon.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsPalestinian Prisoner’s Day: How many are still in Israeli detention?

‘Mama we’re dying’: Only able to hear her kids in Gaza in their final days

Europe pledges to boost aid to Sudan on unwelcome war anniversary

It is not known how these workers died as no investigation into the circumstances of their deaths was launched. The story garnered little attention in Lebanon.

Under the country’s kafala (or sponsorship) system, the legal status of migrant domestic workers is in the hands of their employers. If the employer terminates their contract, the sponsorship gets automatically cancelled, turning these workers into illegal aliens and putting them at risk of arrest and/or deportation. In addition, although confiscating passports is forbidden by law, even Minister of Labour Camille Abousleiman admitted that it still happens.

In effect, this means that foreign workers, most of whom are women, have very little means to defend themselves should the employer abuse them in any way or refuse to pay their salary, let them call their family back home or allow them to take breaks on Sundays.

If out of desperation they flee, they automatically become undocumented migrants. On the streets of Lebanon, they can find themselves as vulnerable, if not more so, than they were in their abusive workplace. If caught, they could be thrown in prison. In some, but by no means rare, cases, they end up killing themselves or being killed.

Currently, there are approximately 250,000 foreign workers – some facing abuse – in a country of more than five million which finds itself at a unique moment in history.

Today the Lebanese people are rebelling against their own abusers, the warlord-oligarch class that have dominated Lebanese politics for three decades since the end of the country’s civil war. Sectarianism, the system which pits the Lebanese against one another based on their religious denominations, is being actively challenged in the streets.

We are destroying sectarian barriers at an incredible speed. We are, quite literally, connecting north and south in a way that has left our parents’ generation baffled. Whatever happens next, what has already been achieved in the past month will resonate for years to come, and shape a whole generation, Generation Z, in a way that has even taken many millennials by surprise.

We now chant “all of them means all of them” to demand the resignation of the entire sectarian political class and to demand dignified lives for ourselves in our own country, the respect of human and civil rights.

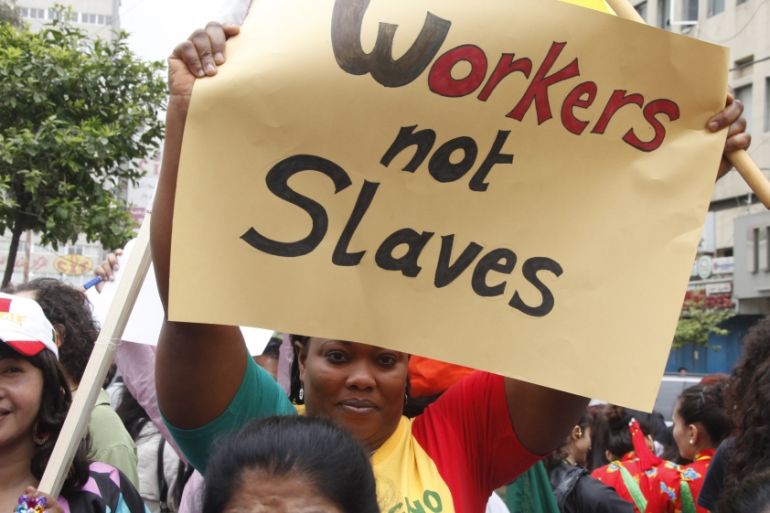

But if we are calling for our rights, we need to be extending our concerns to foreign workers as well. The same system that we are seeking to change is abusing hundreds of thousands of foreign workers. This is why the Lebanese revolution must also call for the abolition of the kafala system.

According to Lebanon’s own intelligence agency, two foreign workers die on average every week. According to a 2008 Human Rights Watch (HRW) report, roughly half of reported deaths are “classified by embassies” as suicides. In 2008, the rate was more than one a week.

In addition, foreign female workers have been arrested and deported for the “crime” of giving birth in Lebanon. Since at least 2014, several NGOs have been raising the alarm over the Lebanese government’s practices of deporting migrant workers and their children and sometimes their mothers. In many cases, these women were told that “they were not allowed to have children in Lebanon” and were given as little as 48 hours to leave the country.

And just last year, a Kenyan woman was deported after being brutally attacked with her friend by a mob in Beirut, leading many to highlight the dangers faced by men and women on the streets of Lebanon.

Currently, the government’s official position on the kafala system is to keep it for as long as possible, regardless of the suffering caused. In practice, this means excluding migrant domestic workers from Lebanon’s labour laws.

In 2019, Georges Ayda, general director of the Ministry of Labour, argued that the kafala system was needed because “you are putting a stranger within a family. When they work in houses there has to be somebody that is responsible for them.” Although Abousleiman himself likened it to “modern slavery“, it remains in place.

Comments like Ayda’s are fairly common in Lebanon and have been used time and again to justify the quasi-slavery-like conditions that migrant domestic workers are forced to work in. The fact that migrant domestic workers are also at risk when living with strangers, is ignored.

Today, there is a severe shortage of empathy towards these working-class women of colour across the Lebanese population, among protesters and supporters of the government, due to decades of normalised violence facilitated by the kafala system.

This is despite the fact that workers’ rights have been regularly brought up during the protests. Unlike previous large-scale protests, this protest wave has seen a very strong working-class presence throughout the country. It should thereby be relatively easy to include foreign domestic workers in our list of concerns.

There have already been efforts to address the issue. In 2014, the Domestic Workers’ Union (DWU) was established by six Lebanese workers and included, from the start, at least 350 foreign domestic workers of various nationalities.

The DWU has received the support of more than 100 non-governmental organisations since 2015, in addition to the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF), the International Labour Organization (ILO), the International Trade Union Federation (ITUC), and the Federation of Trade Unions of Workers and Employees (FENASOL) in Lebanon. But the labour ministry has denounced the DWU as illegal.

Over the past month, there have been efforts to bring up the issue of the kafala system during demonstrations. They have led chants against racism during some of the marches, seeking to draw attention to the plight of both African and Asian workers and refugee Syrian and Palestinian populations.

There have also been marches organised in response to the xenophobic narrative being promoted by segments of the Lebanese political class and their affiliated media stations. Feminists, both Lebanese and non-Lebanese, are currently leading efforts to bring up the issue of discrimination and the kafala system, which is no coincidence, given the ways patriarchy, racism and sectarianism intersect.

But much more serious action is needed. The Lebanese revolution should demand the abolition of the kafala system and the recognition of the DWU, which supports both Lebanese and migrant domestic workers, as a very first step.

The sectarian system being opposed on the streets of Lebanon is inherently tied to the same patriarchal structures that oppress Lebanese and non-Lebanese women and LGBTQ+ as well as to the same racist structures that oppress women of colour, most notably foreign domestic workers.

The sooner we make these links, the better equipped we will be at countering the counterrevolutionary forces that are already feeling threatened by the ongoing uprising. Only through an intersectional framework would we be able to resist attempts to throw vulnerable groups of people under the bus while the rest of us protest for our dignity.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.