The growing threat of sectarianism in Malaysia

The Saudi-Iranian rivalry is raising sectarian tensions in Malaysia and threatening its security.

When the new Malaysian government came to power in May 2018, it made several moves indicating that it would not pursue a policy of favouring one foreign power over another, especially in the Middle East. The new leadership was eager to assert that they will allow neither Riyadh, nor Tehran, to drag Kuala Lumpur into their regional squabbles. But just over a year later, it appears the desired balance has proved impossible to maintain.

The recent escalation of tension between Iran and its American and Arab adversaries has stirred sectarian sensitivities not only in the region but also miles away in Southeast Asia, and caused Malaysia, a country with a predominantly Sunni population of 31 million, to once again get sucked into the foreign rivalries.

Foreign policy and anti-Shia sentiments

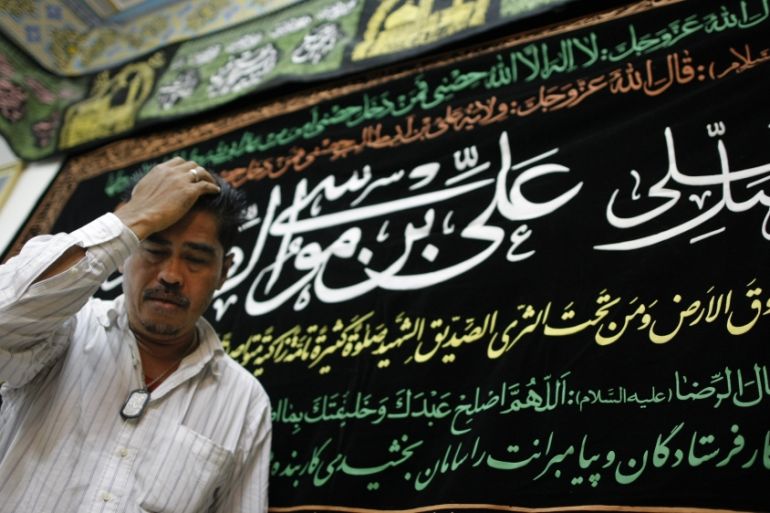

Back in 1996, the Fatwa Committee for Religious Affairs in Malaysia issued a religious opinion recognising Sunni Islam as “the permitted form of Islam” in the country and branding Shia Islam as “deviant”. In doing so, it prohibited the Shia Muslim community, which has around 250,000 members, from spreading their beliefs and allowed Malaysian security forces to raid Shia gatherings.

During this time, calls for the eradication of Shia Islam became a regular component of Friday sermons in many Sunni mosques and persecution of Shia Muslims became commonplace across Malaysia.

By outlawing Shia Islam – the dominant religion in Iran – Malaysia aligned itself openly and firmly with Tehran’s main regional rivals, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi. This, in turn, encouraged the anti-Shia prejudices of the public and allowed sectarian tensions to fester among the general population. It also enabled the spread of Saudi Wahhabist beliefs among Malaysian Muslims.

Riyadh’s influence over Malaysia and the public’s anti-Shia sentiment increased further in 2009 when Najib Razak became prime minister and began cosying up to the kingdom. In the 2010s, anti-Shia sentiment in Malaysia reached its peak as a result of the Syrian civil war, which was often inaccurately presented in the public sphere as a clash between Sunni and Shia forces. The media, even public-owned channels, would often demonise the Shia community, spreading false information about their practices and accusing them of conspiracies.

In 2016, activist Amri Che Mat was forcefully disappeared in the northern state of Perlis after he had been accused of “spreading Shia beliefs” by a local mufti. Recently, the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (Suhakam) concluded an investigation which found that “agents of the state” carried out the enforced disappearance.

Malaysia eventually also got involved directly in one of the Middle Eastern conflicts with a clear sectarian dimension. In 2015, Najib joined the Saudi-led coalition fighting the Iran-backed Houthis in Yemen and sent Malaysian troops without obtaining prior approval from the cabinet.

Deep-rooted sectarianism

The political tide started to turn when the 1MDB scandal toppled Najib’s government. Riyadh was accused of not only playing a role in the scheme, but also helping to cover it up.

When Pakatan Harapan (PH), the coalition headed by Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, came to power in May 2018, it immediately demonstrated that it has no interest in siding with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi against Tehran by shutting down the Saudi-backed King Salman Centre for International Peace (KSCIP) and pulling its troops out of Yemen.

With these two groundbreaking moves, the members of the new government made it clear that they were recalibrating Malaysia’s foreign policy – as they had pledged before their ascent to power – and were stepping out of Riyadh’s zone of influence.

Despite the new government’s best efforts, the anti-Iranian sentiment in Malaysia has proven too strong to beat. Even though Malaysian public was made aware of Saudi Arabia’s role in the country’s corruption scandal, its ever-improving relations with Israel, its role in the Yemen war, and its attempts to whitewash China’s persecution of the Uighurs, they have refused to see beyond the sectarian propaganda they have been fed for decades and reasses their support for Riyadh or their blind condemnation of anything related to Shia Islam or Iran.

Efforts to address sectarianism in the country repeatedly fell on deaf ears, and at times even faced threats of violence. On July 10, for example, a seminar on sectarianism organised by the International Institute of Advanced Islamic Studies, a Kuala Lumpur-based think-tank, was called off over a bomb threat made on an anti-Shia group on social media.

The Facebook group named Gerakan Banteras Syiah (an Anti-Shia Movement), where the bomb threat was made, had over 19,000 followers at the time of writing and it is only one of the dozens of Malaysian social media pages dedicated to anti-Shia hatred.

Earlier in May, members of a charity group which distributed leaflets in Kuala Lumpur on the life and deeds of Hussain, the grandson of Prophet Mohammed, were accused of trying to spread Shia Islam. Although they were reportedly Sunni, they told local media that they had received threats of violence online.

Instead of taking measures to guarantee the security of the group, the Malaysian police said it will work with religious authorities to stop them, demonstrating that it embraced the sectarian beliefs of the general public.

Some mainstream Malaysian media organisations have continued to demonstrate similar biases. They also favour Saudi Arabia over Iran in their coverage.

In late April, for example, Malaysia’s Defence Minister Mohamad Sabu made a working visit to Iran, but the story barely received any coverage other than short, matter-of-fact reports. And when an Iranian delegation visited the Malaysian Parliament on July 4, some media outlets reported on claims that the visit was proof of Shia Islam “spreading its wings to the Malaysian parliament“.

Meanwhile, the local media widely covered Malaysian Sultan Abdullah and Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah’s July visit to Saudi Arabia. Many media reports on the visit even mentioned the “special relationship” and “fraternal bond” between the two countries.

No matter how much Malaysia’s new government tries to stay out of sectarian squabbles in the Middle East and to focus on its policy towards Japan and China, the country’s demographic make-up, and the Middle Eastern powers, which view it as an important ally and a lucrative market, pull it back in.

If the new government fails to send a clear message to both Riyadh and Tehran that it would not be part of their cold war and take swift action to end sectarian sentiments of the population, Malaysia may pay the price and become a new front line for sectarian confrontation.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.