As we fight COVID-19, we should turn our gaze to space

Space exploration can teach human solidarity when we need it the most – amid a pandemic.

Humanity is facing an invasion. In the span of a few months, an invisible outside force we about which we know very little about has killed hundreds of thousands and wreaked havoc in all corners of the world.

Humans have long wondered what would happen in such a scenario. World literature and cinema are full of fictional stories about deadly attacks by “aliens” from other worlds. In most of these stories, human beings put aside their differences and come together to fight the common enemy. They unite under the banner of saving humanity, its creations, its values and the planet it calls home.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsHong Kong’s first monkey virus case – what do we know about the B virus?

Why will low birthrate in Europe trigger ‘Staggering social change’?

The Max Planck Society must end its unconditional support for Israel

This sadly did not happen when a real invisible enemy, COVID-19, started attacking us indiscriminately. Rather than coming together, we embarked on a blame game and turned on each other.

If we want to efficiently tackle this public health emergency and be better prepared for future common threats that we will most certainly face as humanity, we need to realise that despite all our real and imagined differences, our only path to survival is through solidarity. Like the heroes in our fictional stories about alien invasions, we need to come to an understanding that we – the 7.5 billion human beings living on this planet – are in this together.

In order to better understand how we could reach this solidarity, it could be useful and enlightening to briefly review the history of the messages we obtained from space.

Exploration of space, the great unknown that has been a source of wonder and fear for humans since the beginning of history, can provide an opportunity to unite humanity. It can provide the perspective we need to clearly see our shared destiny and act accordingly.

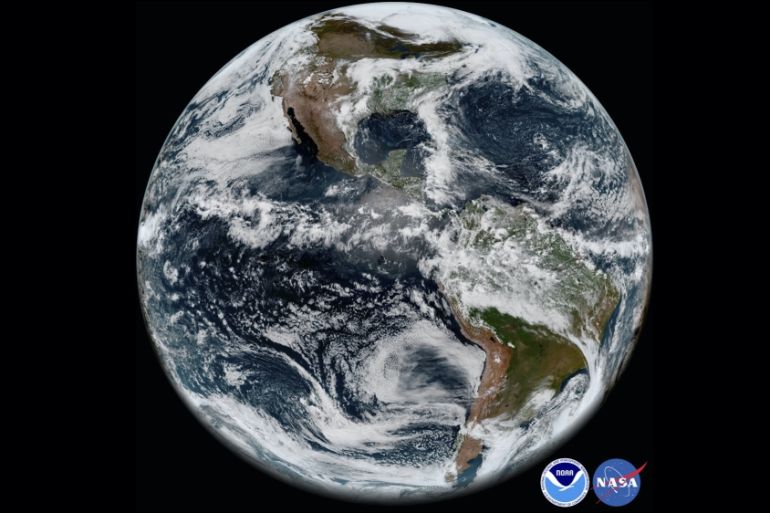

When you pass the Karman line – the outermost boundary of Earth’s atmosphere at 100km altitude – you find yourself in space. Astronauts who go beyond this line get to look directly at the universe. They see bright stars, our galaxy and the vast darkness beyond. They see the boundary between the Earth and space with a thin layer of atmosphere, the clouds, ocean and land moving quickly under them. When they turn their gaze on to the surface of the planet, they see the indescribable beauty of jungles, oceans and deserts like never before.

Looking down on Earth from above, they often find themselves in awe of the human race, who invented the technologies that made it possible for them to travel into space. But they also come to realise how small, and even insignificant, human beings are compared to the magnificent globe they call home – indeed no human, however powerful and rich can be seen from that altitude, only oceans and lands.

This is why astronauts who travel beyond the Karman line often return home as avid environmentalists, advocates for international cooperation, supporters of sustainable development and world peace.

Some astronauts get to go even beyond the Karman line, as far as the geostationary orbit, the Lagrange point 1 of the Earth-Moon system or the lunar orbit. A lucky few have even stepped on the surface of the Moon.

The astronauts who venture into outer space get a rare opportunity to see their home planet in its entirety – a small ball rotating in a vast, dark universe. One side of the small ball, illuminated by the Sun, shines with blue and white colours. On its dark side, lightning can be seen from time to time. From that vantage point, it is impossible to avoid being struck by the uniqueness of planet Earth and its human inhabitants.

As far as we currently know, Earth is the only planet in our system inhabited by intelligent life. We are the only species, at least in our immediate neighbourhood, that is capable of exploring space and looking at its planet of origin from afar.

Once you see Earth and its inhabitants from this point of view, it becomes clear that our differences are not at all important. We may have different skin colours, different cultures, different religious beliefs and nationalities, but essentially we are all the same. We are all members of the only intelligent species in the solar system.

We are all human beings. We can make tools and communicate using complex languages. We can make music and art. We can create glorious technologies. Space exploration, by allowing us to look at ourselves from afar, can help us appreciate the unique beauty and value of being human.

But space exploration can even take us beyond the Moon and the boundaries of our solar system. The first exoplanet – a planet that is outside of our solar system – was discovered in the 1990s. Since then, astronomers have discovered more than 4,000 such planets. Many of those planets are known to have liquid water, meaning they are capable of hosting life. No doubt there are living beings on some of these faraway planets. There may even be intelligent life on a few of them.

We are not yet capable of travelling to these planets, but merely being aware of their existence gives us important insights, and raises crucial questions about ourselves and our place in the universe.

Are there other civilisations on these planets? If we eventually find another intelligent species, can we – or indeed should we – get in touch with them? Will our cultural, technological and perhaps biological differences make it impossible for us to communicate? Will these intelligent “aliens” come and destroy us if we make our existence known to them, as often we imagine in our fiction films and novels?

In reality, it is highly unlikely for a highly developed civilisation to travel all the way to our solar system to kill us or steal our resources. There is, after all, energy everywhere in the universe. So if an intelligent civilisation comes to visit us, or if we manage to visit another civilisation based on an exoplanet, it would be for the sole purpose of discovery.

All this may or may not happen, but simply looking at exoplanets and thinking about how we can communicate with alien civilisations can make us appreciate the value of communication, cooperation and cultural exchange on Earth. As we focus our energy on meeting other intelligent species, we can come to understand how small all the literal and figurative distances between human beings are.

At this point, one may ask whether space exploration benefits only the few astronauts, astronomers and other scientists who get to do the exploring. This certainly is not the case. Today we have books, media and the internet. Our body of knowledge on space and the experiences, feelings and thoughts of the lucky few who get to go there, are widely accessible to many around the world. We can read books and articles written by astronauts, and even watch the videos they film while on the International Space Station.

Space exploration is not only a way to find new worlds and acquire more knowledge about the universe, but it is also an opportunity for us to remember the unique characteristics and privileges that bond us all together.

We, the three authors of this article – one engineer, one scientist and an astronaut – come from three different continents and have contributed to humanity’s ongoing quest to understand and explore space in very different ways. Our work helped us develop a passion not only for our planet but also for all of its inhabitants.

We believe by promoting space exploration and even space tourism, making information on space even more accessible, and listening to the insights scientists, astronauts and even tourists gain through venturing into space, we can make human beings come together to protect our planet and our future.

If our political leaders take the time to gaze into space and think about how we share a destiny on this beautiful blue marble travelling alone in the universe, they can perhaps move on from petty squabbles and start working together to protect the interests of not only “their people” but all of humanity.

Every single one of us, after all, are crew members of planet Earth.

Charles Frank Bolden Jr, who is a former NASA administrator, a retired United States Marine Corps Major General, and a former astronaut, is a co-author of this article.

The views expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.