Fatah and Hamas will face Trump’s deal disunited

And it will be a disaster for the Palestinian struggle.

It’s been more than a year now that the Trump administration has been talking about the “deal of the century” to bring some form of settlement to the Palestinian question in the Middle East.

Bits and pieces of the deal have been leaking: the siege on Gaza is to be lifted, its residents provided with humanitarian aid, while East Jerusalem and West Bank settlements are to be recognised as Israeli territory; Palestinian refugees will have to give up their right of return.

President Donald Trump and his Middle East team, led by his son-in-law Jared Kushner, seem to have secured an implicit backing of the deal by strategic players in the Arab world such, such as Saudi Arabia.

Recent diplomatic initiatives by Israel in Gulf states have borne fruit and it is increasingly clear that they have set out on a course towards normalisation of relations.

The murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, the US midterm elections and a number of other factors delayed the unrolling of the deal but it cannot be postponed for that long. Israel is set to hold parliamentary elections in November 2019 and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu sees the deal as a political victory that could guarantee him another premiership.

Thus, the Trump administration is likely to press forward with the deal sometime in the first half of 2019. And on the eve of this certain disaster for Palestinians, the Palestinian political leadership stands disunited.

Relations between Fatah and Hamas – the two main political factions in Palestine – are at an historic low and seem to be getting worse.

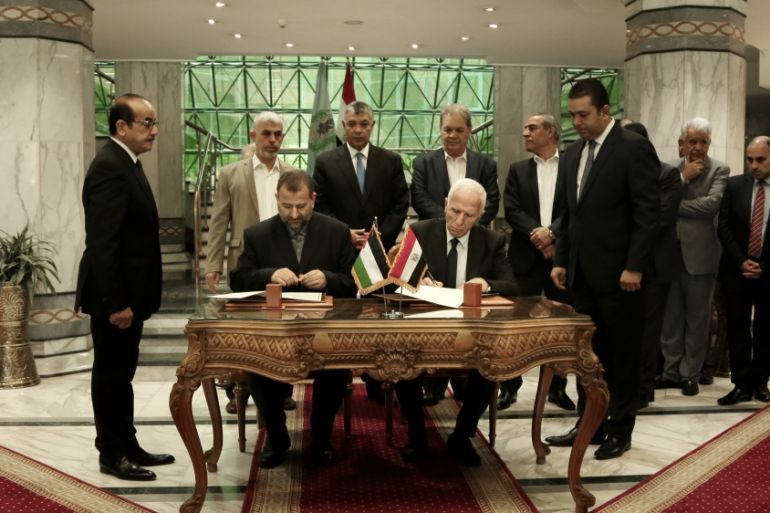

It has been 12 years since the two parties clashed in Gaza in the aftermath of the legislative elections, effectively creating two axes of political power in the Palestinian territories. And it’s been 11 years since Arab states started trying to broker a reconciliation between the two. Every time – in Mecca (2007), Sanaa (2008), Cairo (2011), Doha (2012), and Gaza (2014) – an agreement was signed but never implemented.

There was hope that the last Israeli assault on Gaza in November this year would bring the two sides together and would enable them to get over partisan and personal interests. Therefore, Egypt, which is currently leading another attempt at reconciliation, called on the leadership of both movements to come together for new talks and invited delegations from both sides.

But its efforts ended in failure after Fatah and Hamas exchanged hostile statements, accusing each other of wrongdoing.

Fatah declared it would not reconcile and participate in a unity government with Hamas until the latter rolls back the “coup” it carried out in 2007. It also signalled that it would look into imposing additional sanctions on the Gaza Strip, adding to the ones that have been in effect since 2017, to press Hamas to give up power. The Hamas leadership responded that its government is legitimate, as it won the 2006 elections, and accused Fatah of playing “politics of arrogance” and trying to undermine its power in Gaza.

Thus, Egypt’s reconciliation efforts ended yet again in a regrettable failure, and no new initiative is expected to be launched in the foreseeable future.

One of the main points of contention currently between Fatah and Hamas is the ongoing negotiations over a truce between the latter and Israel. A number of local, regional and international bodies have been trying for some time to bring about an agreement between Hamas and the Israeli government for a more permanent ceasefire and some form of lifting of the debilitating siege imposed on Gaza for the past 11 years.

Fatah – and by extension the Palestinian Authority (PA) it controls – sees this arrangement as highly problematic because it deals with the Gaza Strip as a separate geographical entity from the West Bank. And given that the mass expansion of illegal Israeli settlements in the West Bank over the past few decades has made a declaration of a Palestinian state in its area impossible, Fatah and the PA leadership fear Gaza could be given that status.

This would effectively mean the complete sidelining of the party and its leadership (given that the Strip is under Hamas’ control politically and militarily) and the relegation of the PA to an administrative authority (and not a sovereign state structure), managing the affairs of the Palestinian population in the remaining pockets of territory outside Israeli settlements.

To preclude such a development, Fatah has demanded that a unity government is formed, whereby Hamas relinquishes control over the government, economy and security in Gaza and the model of governance currently in place in the West Bank is transferred to the Strip. Hamas has outright rejected these demands because they effectively mean that Gaza would slip out of its grip.

The group insists that it should participate in the unity government as an equal partner, along with other Palestinian factions, and rejects the extension of the PA’s security policies and model (especially cooperation with the Israeli security apparatus) into the Gaza Strip. It has also made it clear that it will resist any pressure from the PA to disarm its military wing.

The persistent squabbling and disunity between Fatah and Hamas are detrimental to the Palestinian cause and are resulting in increasing disillusionment among the general Palestinian population. Although both factions claim to have the legitimate right to power, political legitimacy is difficult to gauge in Gaza and the West Bank, given that there haven’t been legislative elections since 2006 and PA President Mahmoud Abbas has not faced a vote after his term expired in 2009.

As Fatah and Hamas trade accusations of aiding the deal of the century, their political disunity is what would ultimately allow for its implementation. Hostility between the two factions would facilitate the political separation of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, in which Egypt is likely to take over economic and security supervision of the former, while Jordan will have some form of authority over the latter.

This would not only preclude the declaration of a viable Palestinian state that satisfies Palestinian aspirations and solidify Israel’s denial of the Palestinian right to return but would also deal a major blow to the popularity and legitimacy of both Fatah and Hamas. At this time, it is clear that it is in their best interest and that of the Palestinian people that they overcome their disagreements and stand united.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.