Detroit: A film by white people for white people

On the 50th anniversary of the 1967 rebellion, Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit fails to tell the full story.

Earlier this month, the film “Detroit” opened in theatres all across the United States. Produced by Academy Award-winning director Kathryn Bigelow and writer Mark Boal, the movie was right on time for the 50th anniversary of the historic 1967 Rebellion.

The 30-million-dollar film starts with a convincing depiction of what triggered the unrest and moves quickly to the city’s Algiers Motel, where three black men were murdered by police officers. The officers responsible for the killings were later acquitted.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsFormer US police officer sentenced in killing of Black man Elijah McClain

US paramedics found guilty in 2019 death of Black man Elijah McClain

Angela Davis: ‘Palestine is a moral litmus test for the world’

|

|

The spark that set the fire of rebellion was the busting of an after-hours joint – a blind pig – in the heart of a black neighbourhood. The community swiftly responded to the raid: Detroit burned for five days, 43 people died, 1,189 people were injured, over 7,000 were arrested and more than 2,000 buildings were destroyed. The national guard was brought in. It was a catastrophe that would change the city forever.

Inspired by the 50th anniversary of the rebellion, I came home to Detroit this past Memorial Day to present my annual Burn and Bury Memorial ritual – a mock funeral for and cremation of the Confederate flag featuring some of the city’s finest poets and activists – to an audience gathered at the N’Namdi Gallery. The ceremony took place a few weeks before the official commemoration of the 1967 rebellion, which included a full programme of events led by the Detroit Historical Society, Wright Museum, and Detroit Institute of Arts, demonstrating how special the anniversary is for Detroit.

And since I was in Detroit and in utero during the summer of 1967, this time in history is particularly meaningful to me – the stories, the burned out remains, the pain, the expression, and the need to resist and rebel against the historical gravity of American white supremacy. And so, I was very excited to see this movie.

A horror flick without context

My excitement about Bigelow’s “Detroit” was quickly eclipsed once I got past its beautiful and powerful opening scene, which features lightly animated variations on Jacob Lawrence’s painting series on the Great Migration. And by the time the film ended, I felt like I had watched a mash-up of Get Out, Five Heartbeats, and the most brutal parts of 12 Years a Slave.

The film was not really about the complex factors and stories that led to and sustained five days of activity. It was a sub-narrative dramatisation of mass murder and psychological pathos about what happened in a motel – a worthy of story and film all by itself. And the film works better this way, if the expectations were restricted to this important story.

READ MORE: 1967 Detroit riots, ‘resistance’ then and now

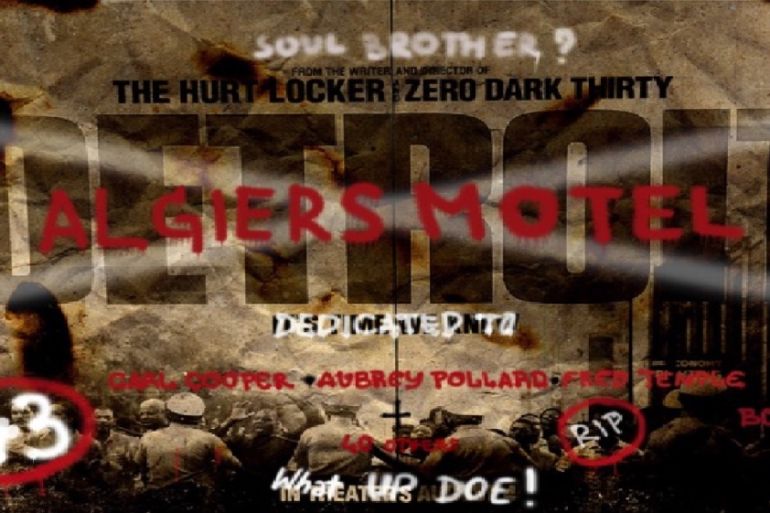

The film’s title is the first problem. The film should have been called “Algiers Motel” and not “Detroit”. The naming of the film is clearly an exploitative strategy timed to take advantage of the anniversary of the city’s rebellion. Producers appear to be cashing in on growing national and international interest in the Motor City, which is on the verge of a very curious, white-ish comeback.

Even the gigantic pop-up promos of the film, exhibited at theatres around the country, are misleading and require correction as they fail to communicate to potential audiences the real content of the film. When you study the production credits, and follow the reviews, it becomes clear that this is a movie by white people for white people. I think they call that “Hollywood”. So, where are my matches and spray paint? (see results in the above art image).

While I appreciate how Hollywood can bring important stories to a national audience, I question if white directors, writers, artists and producers are feeling more and more comfortable telling stories that centre around black pain, trauma, and resistance, profiting in ways that comparable black storytellers can't.

The storyline of the film is riveting, but also problematic on many levels. What happens when you put a bunch of black men in a confined space with white party girls, then add some racist cops and the National Guard? You get a horror flick and anything going on outside the motel becomes a distraction, even if it is a rebellion brought on by decades of segregation, police brutality and general racism.

The story presents the great American threat – the black men, the ones that might shoot back, the ones that might pimp some white girl or deal drugs or steal property – being punished by the first line of defence of white supremacy: the police.

And the one character that had a big dream, an American dream, one you may have rooted for to survive, is the one person who refuses to sing for you in the end. His only form of protest left was to riot against his own talent and murder off his opportunity for greatness. This story is all too familiar – just check the American prison system.

With the hollow character development, the minimal political context surrounding the rebellion, and evidence that the writers may love Motown’s music more than its people, I struggled to find an emotional connection deep enough to offset the pornographic violence featured in the film.

We’ve all seen the current level of raw police brutality against black men, but what needs elucidation, as much today as ever, is the fundamental inequality that created conditions for the rebellious response. I have to wonder if this Passion of Christ level of brutality is what drives the white guilt that fuels temporary race-based empathy.

While the tension between good and evil, good cop and bad cop are great devices to drive a Hollywood story, in this film, the excessive humanisation of white cops is unbelievable, unfair, and is used as a way to shift blame to a few bad guys, obfuscating the real culprit – the whole system. Since the principal bad cop in the film, who is presented as the main culprit behind the three murders, is largely fictional, one wonders how about the acceptable ethical level of manipulation in creating definable objects of blame.

Who owns Harlem or Detroit?

While I appreciate how Hollywood can bring important stories to a national audience, I question if white directors, writers, artists and producers are feeling more and more comfortable telling stories that centre around black pain, trauma, and resistance, profiting in ways that comparable black storytellers can’t.

But the bigger question or concern is: Who owns political and cultural experiences and stories? Who owns Harlem or Detroit? Who owns the stories of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion and who should tell and produce them? Who are allowed to respond? This makes me think about Tarantino’s Django Unchained, artist Dana Shultz’s controversial Emmett Till painting, and HBO’s Confederate – a new TV series developed by producers David Benioff and DB Weiss, creators of the very popular “Game of Thrones”.

Bigelow admits in an interview with Variety magazine that she might not have been the best director for the film, but she was the one who could do it. So maybe a more fitting pathological thriller would be to do a film on the dynamics behind the very recent and deadly “Unite the Right” aka neo-Nazi/Confederate/Right reunion in Charlottesville, Virginia. While I give Bigelow much credit for being honest, it is a bold statement of privilege – Norman Lear’s Good Times kind of privilege – that good ole white privilege. So much for black privilege in such matters of art, stories and film.

Black productions matter

Sometimes these dynamics produce a situation where one is not sure whether to feel honoured, cheated, or both. While “Black Stories Matter”, so do black productions.

|

|

Cultural and political production should not be without allies and comrades from different backgrounds and experiences. Artists should be able to tell stories across cultural lines, provided it is done with respect and grace, not out of a paternalistic or maternalistic, saviour complex or solely for profit.

For instance, John Hersey, a white, male, Pulitzer Prize-winning author, wrote the book, Algiers Motel Incident. His grandson, Cannon Hersey – an artist and activist who was just recently in Detroit doing social justice projects – informed me that his grandfather gave up all of the proceeds from the royalties, much of it going to a scholarship fund for African Americans. Not wanting his work to be exploited by Hollywood, his family refused to sell the rights to the book.

This is probably why Boal had to organise his own research team to write the script. This sort of understanding is more the exception than the bottom-line rule. I wish Bigelow and Boal moved in the same way. I wish the producers had included a scene or two about the mock trial Shrine of Black Madonna, a Pan-African Orthodox Christian Church, organised for the three cops, who were acquitted in the real courts.

I wish there had been a black woman’s voice somewhere, anywhere. I wish the whole film had been shot in Detroit rather than in the faraway city of Boston. This would have given Detroiters the opportunity to be a part of the re-enactments and space to witness how art can promote discourse from the inside out. And if there was one, I must have missed it.

READ MORE: Grisly Halloween display in Detroit decries US violence

As we approach a very rare total solar eclipse on August 21, I am drawn to think that after all is gone in the shadows, all that is left are stories. If those on the forefront of experience do not tell these stories loudly, others will, in ways that might eclipse the truth, and justice, and faith, leaving behind a darkness – whispers of a lost opportunity for real healing and redemption.

So I hope that when its centennial comes around in 2067, someone among us, maybe someone in someone’s womb at this very moment, will get the support to do a dramatic feature on the whole story of Detroit 1967. I hope it will, upon another 50 years of reflection, finally be told right, more impactfully, more inclusively and in a way that will make Detroiters and their descendants, both black, white and brown, come to know the story of the price, pain and power of resistance and rebellion. But for now, check out the oral histories, exhibitions and all things related to the city’s historic rebellion at the website of the multiyear community project Detroit 67: Looking Back to Move Forward.

John Sims, a Detroit native, is a multi-media artist, writer, producer and creator of Recoloration Proclamation, a 16-year multimedia project featuring a series of Confederate flags installations, The AfroDixieRemixes, the annual Burn and Bury Confederate Flag Memorial Day ritual and a forthcoming memoir.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.