No end in sight for India’s bloody Maoist conflict

India claims that the Maoists are on their way out, but the grievances that gave rise to the conflict are not answered.

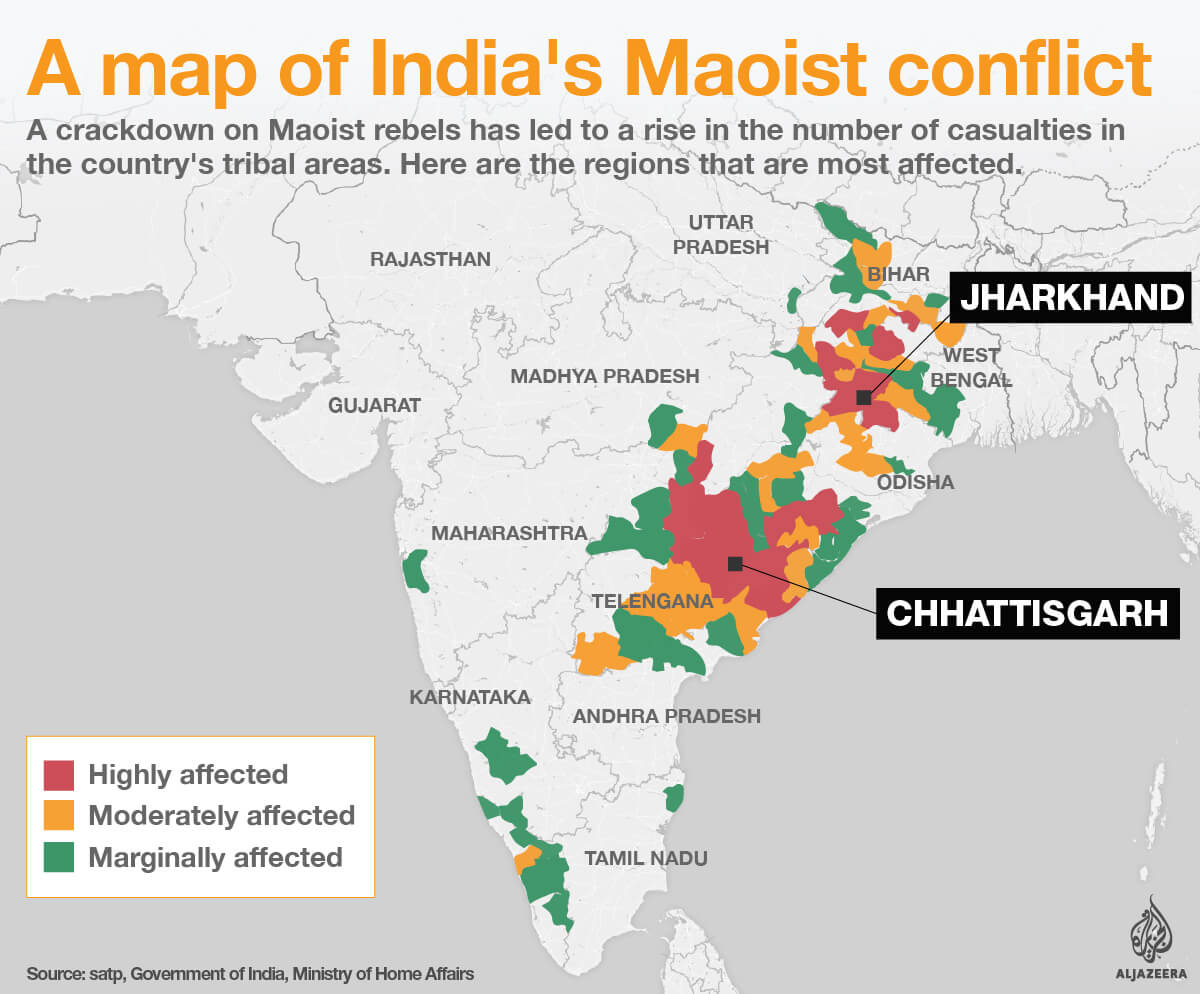

Last month, 25 paramilitary soldiers from India’s Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) were killed in a Maoist ambush in the Sukma district of the country’s central Chhattisgarh state.

Predictably, the media outrage that followed the attack, the solutions offered by security pundits and the statement issued by the Maoists had a strong sense of deja vu.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsBirth, death, escape: Three women’s struggle through Sudan’s war

Does Israel twist humanitarian law to justify Gaza carnage?

Vatican denounces gender-affirming surgery, gender theory and surrogacy

The Leftist rebels, or Naxalites as they are popularly known, have been active in the Bastar division of the Chhattisgarh state, which encapsulates the Sukma district, for more than three decades. They have been taking up issues of land and forest rights for the indigenous people or Adivasis, keeping out mining companies, and establishing an almost parallel state. In the last decade, however, the war between them and the Indian government has intensified, ever since the government sponsored Salwa Judum, a vigilante movement aimed at depopulating the region and forcing villagers into camps.

In April 2010, 76 men from the CRPF were ambushed and killed by the Maoists in the same stretch of the Sukma district. More recently, in March this year, Maoist rebels killed 12 paramilitary men after ambushing their convoy. There have also been several unmarked deaths among the Maoist cadres over the years. But above all, there have been continuous, relentless assaults on the lives and human rights of indigenous villagers across the region.

Assaults on the human rights of Adivasis

|

|

In March 2011, security forces burned down at least 300 homes in three villages in Bastar, a brutal attack during which three men were killed and three women were raped. And this was not the first time that these indigenous villages were burned to the ground: In 2007, men from the state-sponsored Salwa Judum vigilante movement, which included members of the security forces, had burned down the same villages.

To this day, villagers across the Bastar division of Chhattisgarh are living lives of desperate fear. First of all, they are under the pressure of sustained combing operations. Security officers pick up men sleeping in their homes or minding their business in the market. They claim that these men confessed to being Naxalites and surrendered to the security forces. Government data, however, reveals that of the 1210 people who “surrendered” in Bastar in 2016, only some three percent have been classified as real Naxalites.

READ MORE: India’s Maoist rebels – An explainer

Indigenous women are also subject to government pressure and they are often brutally beaten for trying to resist attacks by security forces. India’s National Human Rights Commission acknowledged that between November 2015 and January 2016, indigenous women in Chhattishgarh suffered three major incidents of mass gang rape and physical assault at the hands of security forces.

More recently, on April 2, 2017, a 14-year-old girl was sexually assaulted in her home in a Sukma village by CRPF men. After spending three days in police custody, she was forced to retract her statement – she was not even allowed to meet the women’s rights activists who were trying to help her file a complaint.

But people of Bastar are not only suffering at the hands of security forces. On their part, the Maoist rebels seem to have turned inwards on their peasant base, killing and threatening any potential informers.

It is true that the Maoist footprint has considerably reduced since their peak in 2008-9, that many senior leaders of the movement have been arrested or killed, and public sympathy is waning, but for a movement which celebrates its golden jubilee this year, the conditions that gave rise to a sense of deprivation and injustice have not changed.

Given this pincer movement from both the state forces and the Maoists, it is hardly surprising that the local population is not willing to provide intelligence about impending ambushes.

The way forward

Every time there is a major attack, India’s security establishment talks of the need to maintain standard operating procedures, to send in more boots on the ground, to fill vacancies in the state police forces and so on.

After the latest ambush in April, the Maoists made off with AK-47s, under-barrel grenade launchers, LMGs, INSAS rifles, AKM assault rifles, wireless sets, binoculars, bulletproof jackets, AK magazines and ammunition – an indication of the kind of weaponry that is being deployed against them.

Every few years, the minister responsible for internal security announces that the Maoists are on their way out and that in a mere couple of years the conflict is going to come to an end. Chidambaram, India‘s former home minister, said this in 2010 and Rajnath Singh, the current home minister, is saying it now in 2017. Only the party labels have changed, from Congress to BJP.

It is true that the Maoist footprint has considerably reduced since their peak in 2008-9, that many senior leaders of the movement have been arrested or killed, and public sympathy is waning, but for a movement which celebrates its golden jubilee this year, the conditions that gave rise to a sense of deprivation and injustice have not changed.

In fact, the situation has got much worse for villagers, with schools, health centres, weekly markets, all becoming casualties of the war, and nutritional standards deteriorating sharply. Even if the movement is militarily crushed in the near future, there is no saying that it will not find willing followers again.

IN PICTURES: India’s Maoist heartland

The Indian government has plenty of resources that it can use to create an alternative mechanism to end the conflict. First of all, there is a constitution that can provide for the welfare of Adivasis or scheduled tribes if it is implemented.

Also, the government has a past record of successful peace talks with the secessionist Mizo National Front in Mizoram. There are international examples of negotiated settlements between left wing guerillas and the government, and an active human rights community which has in the past shown a desire to mediate talks between the Indian government and the Maoists. Even the Indian Supreme Court has invoked the example of the Colombian peace talks while hearing petitions related to ongoing human rights violations in Chhattisgarh.

Unfortunately, there is more money to be made in war than in promoting peace.

Nandini Sundar is Professor of Sociology at the Delhi School of Economics, Delhi University. She is the author of The Burning Forest: India’s War in Bastar, published by Juggernaut Press in 2016.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.