Human genes in court: Discovery or invention?

The struggle over ownership of human genes continues in the Australian courts, with international implications.

This week, Maurice Blackburn announced that the legal challenge to the patenting of human genes will continue and it will file an appeal in the case against Myriad Genetics in the Federal Court.

The original decision upheld a patent over genetic mutations which are associated with an increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer. The Court decided that the isolated genes were patentable on the basis that the gene is extracted from its natural environment by human intervention and therefore constitutes an artificial product.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWoman, seeking loan, wheels corpse into Brazilian bank

UK set to ban tobacco sales for a ‘smoke-free’ generation. Will it work?

Poland lawmakers take steps towards liberalising abortion laws

The applicants in the case argued that the mutated gene is a discovery of a product of nature, not an invention. When it is isolated using well-known laboratory methods, it is not relevantly different from that which exists in the human body.

Myriad Genetics has held the Australian patent since 1994 and provides tests for predisposition to these types of cancer. The company has a monopoly over this testing. It does not currently enforce its monopoly, however it has threatened to do so in the past and presumably may do again. Myriad holds similar patents in other countries.

Some have welcomed the decision as a victory for “innovators” who might not have invested in research and development without the promise of reward. As a preliminary point, this argument fails to acknowledge the amount of public funding that goes into this type of research. Taxpayer money should not fund the surreptitious privatisation of a public service like healthcare.

There are other more general problems that follow from human genes being patentable. There is a significant benefit to the public of being able to study and make productive use of underlying genetic material which is naturally occurring. Denying access to this, in the form of a patent, undermines our ability to make use of the knowledge in innovative ways.

This is the argument of the US government, which has filed a brief in the parallel proceedings which will be heard by the US Supreme Court in April. The US government has concluded that isolated genetic material should not be patentable. For non-scientists, it is a fascinating insight into the world of gene research.

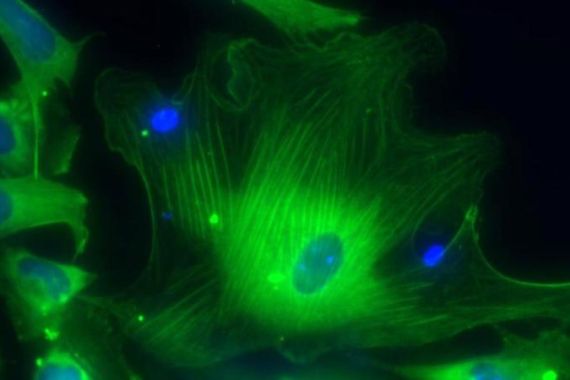

|

Discovering the mysteries of human DNA |

The brief described how the isolation of the genetic aberration at the centre of the case involves extraction and “snipping” of the gene, but notes that it still remains in its natural form. Contrast this with artificially created DNA, which has been put to a variety of different purposes and, according to the US government, should be patentable. Isolation of a naturally occurring gene mutation is akin to discovery of a natural product or law, rather than a creation of human ingenuity.

Indeed, the US government points out that the isolation of genes is often a pre-requisite to exploitation of a substance for serious study or commercial exploitation. To patent it therefore determines how it will be used. Far from promoting innovation, this is actually confining – it “monopolise[s] the law of nature itself”.

Consider the analogy of a lemon: extracting the juice from the lemon has involved human labour, but it has not changed the natural product itself. By patenting lemon juice, the owner of the patent has exclusive rights to make lemon cake. But if we deny others access to lemon juice to study its properties, we might never have created lemonade.

Another brief was filed in the US proceedings by Dr James Watson, a co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, for which he won a Nobel Prize. He eloquently makes the case against patenting, noting that genetic sequencing has the potential to “revolutionise” whole areas of medical treatment.

“A human genome cluttered with no trespassing signs granted by the patent office inhibits scientific progress,” according to Dr Watson, “particularly the development of useful tests and medicines in areas requiring multiple human genes.”

This case raises questions not just about scientific practicalities, but also about the kind of society we want to live in. By patenting genes, we are turning the basic building blocks of life into property; we are putting a price on them.

Harvard Professor Michael Sandal has written about the moral limits of markets, noting the way “market values crowd out non-market values worth caring about”. He calls this the “corrosive tendency of markets”. Are we prepared to entrust our genes to the market?

This legal fight will now continue in the Full Federal Court of Australia. This debate involves consideration of broader policy questions beyond what will play out in legal argument. To date, legislators have not taken the opportunity to reform our patent laws; it has been left to the courts.

Regardless of the outcome of the Australian legal case, it is incumbent on policymakers to grapple with these issues with an eye on what it is that motivates the various stakeholders to take the position that they do.

As Dr Watson concludes: “Life’s instructions ought not be controlled by legal monopolies created at the whim of Congress or the Courts.” These questions are too profound for such treatment.

Rebecca Gilsenan is principal lawyer at Maurice Blackburn and has led the case against Myraid Genetics.

Follow her on Twitter: @WeFightForFair

Elizabeth O’Shea is an associate at Maurice Blackburn and manages its social justice practice. The test case against Myriad is being run by Maurice Blackburn pro bono.

Follow her on Twitter: @Lizzie_OShea