Tahrir and Egypt’s emerging culture of resistance

The same culture of resistance that was present on February 10, 2011, still resounds throughout Tahrir and Egypt.

If the pulse of Tahrir – which has been a very good barometer of the health of the broader revolution in Egypt during the last 23 months – is any indication, Egypt is about to have a new constitution, drafted by a Muslim Brotherhood president and passed by a relatively narrow majority of the population. Not that the protesters in Tahrir are happy about this development. But even before the results of the first round were announced (“Yes” received 57 percent in the official but contested tally), Tahrir regulars seemed resigned to its passage.

As I argued in my last column, despite all the conflict surrounding it, the present draft is not inherently disastrous or even a necessarily bad document, and could serve as the foundation for legislation that provides a gradual but steady increase in the political, economic and social rights of Egyptian citizens.

But such a trajectory would depend on a fundamental transformation in the broader socio-economic structures of Egyptian society, which the still young revolution has not even begun to achieve. Indeed, the forces most responsible for the revolution, and who would have moved it in this direction, have been marginalised in the emerging political order. For their part, rather than challenge the Mubarak-era system, the emerging power elite seems bent on adapting the existing emerging political and existing economic systems to the specific interests and domestic and foreign alliances of its core members.

Moving in such a direction demands the state continue rather than stop its use of violence against citizens. Meetings with human rights activists revealed systematic police abuses and torture to be continuing apace, with little if any change during the transition period, including President Morsi’s time in office. As Aida Seif ad-Dawla of the Nadeem Centre for the Rehabilitation of Torture Victims, describes it, “Morsi is still running with the old regime machinery.” He could have made a clear order to stop abuses of detainees and citizens engaged in protests. He could have begun pushing out the felool (remants of the old regime) inside the Interior Ministry and pressed for far more explicit human rights language in the Constitution, setting a new tone and beginning to hold people accountable.

But as long the Brotherhood and the political Salafis retain the lion’s share of political power, while the army and the economic elite maintaining their Mubarak-era privileges, the new constitutional order and the soon-to-be elected Parliament will bring little positive change to the lives of most Egyptians.

Egypt, right where it should be?

The young people behind the revolution have been particularly marginalised in the emerging political power structure. As well known blogger and former political prisoner Alaa Abdel Fattah explained to me,”There is deep hostility to anyone young who seeks a political or social role.”

| Inside Story Will a new constitution divide or unite Egypt? |

But it is not only the young; nearly half the country feels left out of the emerging order and fears the goals of the revolution – freedom, dignity and social justice – will be lost in the new/old order (compared with this the 78 percent who voted for the interim constitution). There is no way to break this down by class or social markers – young and old, religious and “secular”, poor, working, middle and upper classes, felool and long term Mubarak opponents all share various opinions and sentiments across the lines that are supposed to divide them. The scale of opposition to the constitution tells us that there is a large cross-section of the population that will not put up with the Brotherhood’s clear attempts to reorient the system towards its interests rather than fundamentally transform it for the good of all citizens.

In this regard, however lamentable may be the most recent violence, it has shown President Morsi that not merely that the opposition is too large either to be bought off or crushed, but that it will fight back against any use of violence by the Brotherhood, Salafis or the state more broadly. Most activists I know put more trust in street resistance than in the leaders of the so-called “National Salvation Front” to check the government’s power.

On the other hand, travelling from Tahrir Square to the Freedom and Justice Party rally at the Rabi’a al-Adawi’a mosque on Friday, it was hard to tell the marchers at the two rallies apart, not merely because they looked so similar, but also because so many of the slogans and chants – and even dances – were the same (“No to the military government!” “No to the Felool!” “Freedom, Democracy and Social Justice!” could be heard at both). Religious symbols and a focus on Sharia were more apparent at the FJP rally, but there was a genuine feeling that the soon-to-be ratified constitution will be “the best constitution in Egypt’s history”, as one larger poster put it near the mosque. And indeed, it probably is.

Of course, the nearly ubiquitous support for democracy by FJP voters and politicians must be contrasted with the violence threatened and committed by the Party and its members. This ambivalence exemplifies the difficulties of generalising about the Muslim Brotherhood, which is at once an old and very hierarchical organisation, a political party, a transnational economic network, and millions of citizens who support both today for a host of complex reasons, but might well turn against them if there is little improvement of their lives in the near future.

My guess is that ultimately the JFP is being used instrumentally by a large share of its voters, who will not hesitate to shift their support to other political forces should their lives not markedly improve in the coming years. Then again, the power of conservative religiously-grounded political forces to hold onto voters even when their policies manifestly harm their interests cannot be underestimated, as the example of the US Republican Party has long made clear.

Despite frequent warnings to stay out of Tahrir after dark, the Square remains one of the purest revolutionary spaces on earth in the late night hours. Most of the time it’s mellow, although several times in the last 10 days Tahrir’s defences were tested by unknown (at least officially) groups of attackers, to no avail. Usually, its two-hundred or so tent dwellers pass the night sitting by debris-fed fires or propane stoves, sipping tea, watching videos of the violence on makeshift screens, doing wheelies on motorcycles, or cirumambulating the Square with long 1×4 pieces of lumber. Politics is a constant theme of discussion throughout the night, as its been most every night Tahrir has been occupied going on two years.

‘Violent non-violence’ and popular legitimacy

The revolution has always been led by the praxis of ordinary Egyptians, and that praxis is being conceived of, debated, tested and just plain practiced in Tahrir as much as if not more than at the inummerable NGO conferences or “tweet nedwas“, however important they may be for activists. In that regard, the denizens of Tahrir are doing the yeoman’s work of the revolution; and behind them stands the Ultras, who remain ready to show up with as many molotov cocktails as necessary to defend Tahrir from a serious assault.

Indeed, there is little doubt that if the men and women of Tahrir weren’t willing to spend weeks sleeping in Tahrir – which in comparison to the well-funded Salafi encampment feels like a refugee camp – the Brotherhood and/or Salafis would have taken it over, hijacking the singular symbol of the revolution right at the most important moment of opposition. Activists may lament that the numbers aren’t larger, but a holding pattern is precisely where Tahrir should be right now, as holding Tahrir represent the opposition’s foothold in the public sphere, forcing the political fight into the open where everyone can see it, rather than in the back rooms of the powerful, where it has been for so long.

At the same time, the willingness to use limited violence, not merely in self-defence against attacks by government or conservative forces, but as an active strategy of political conflict, calls into question the broad notions of non-violent civil resistance that have been so celebrated as among the greatest features of the Egyptian and Tunisian revolutions. As Abdel Fattah describes it, what has emerged in Egypt is a new twist to the non-violent resistance methods famously described by Gene Sharp in numerous well-known publications.

“Call it ‘violent non-violence’,” he declared, defining it as an organic reaction by youth-led opposition forces, who themselves were politically weaned on the two Palestinian intifadas, to counter the imbalance in power favouring the state supporters of the emerging political status quo, who won’t hesitate to use violence against them if they don’t forcefully and when necessarily violently stand their ground.

In a manner still not fully understood by scholars of civil resistance or political activists, it’s becoming clear that this use of limited but sometimes intense violence as a method of active self-defence remains a crucial tool in forcing Morsi, the FJP/Brotherhood, and the military/state to reveal their true intentions. It also highlights the systematic human rights violations that no one in power has yet addressed or even wants to discuss. What the Tahrir and Ittehadiyya protests have done is further entrench a “culture of resistance” that is crucial to retaining a credible opposition to the new constitutional and legislative/political order; one which in the present political constellation will most likely be not much more just than the last one.

The question is, how will this dynamic and strategy play out after the passage of the constitution and the election of the new Parliament. The political process may not give Morsi the “popular legitimacy” (ash-shara’iyya ash-sha’abiyya) that he has so desperately sought (the phrase is ubiquitous at FJP rallies), but it will likely help him argue, as he did during a November 29 interview on OnTV, that “the the will of the people cannot be expressed by angry crowds… Revolutionary legitimacy is over, and now it is popular legitimacy that rules” – at least to those Egyptians that voted for the constitution.

Culture still crucial

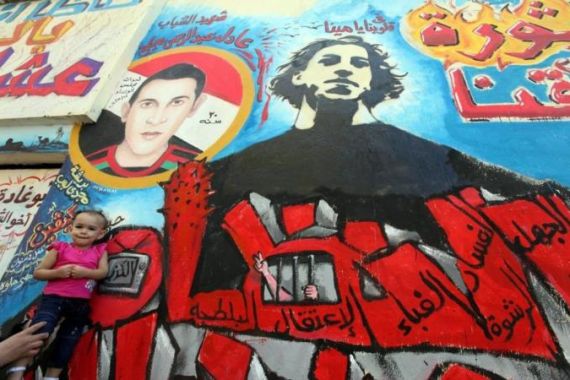

While Cairenes prepared to vote last week, Creative Commons – the global non-profit that promotes the free sharing and use of all forms of intellectual property on the web – was holding a special workshop for Arab visual and musical artists, bloggers, and other cultural creatives in Cairo as part of its tenth anniversary celebrations (I wrote about the first workshop, in Tunis last July, here). Moving back and forth from the streets of the city to the gathering, which brought together artists from upwards of a dozen countries, reinforced my belief that cultural production will be a crucial vehicle both for self-expression and reaching the broader public as Egypt’s opposition forces struggle to settle in for the long hall.

As Creative Commons coordinator and Al Jazeera contributor Donatella Della Ratta explains, “It’s as if all the talent that was compressed under repressive regimes such as Tunisia and Egypt is now exploding. After the first phase of the revolutions in which social media contributed to ‘toppling’ the regimes by spreading information and communicating events outside the region, it’s now time to build on this sharing communities and their creative potential, to find new ways to create together and share the work, and remix the culture of revolution.”

| Omar Offendum on Al Jazeera – #Jan25 Egypt |

For Moroccan metal pioneer and Gnawa funk artist Reda Zine, such gatherings are “revolutionary laboratories. The key is that as artists we don’t just consume but also produce culture. I do a lot of work in Europe, and there’s no more groove there. Here is where the groove is at.”

Whether it’s Egypt’s once beleaguered metal scene, whose angry and brutal music (see bands like Scarab, Massive Scar Era and Dark Philosophy, to name a few) was the perfect soundtrack for life in the late Mubarak years, or the revolutionary rock and hiphop of artists like Ramy Essam and Arabian Knightz, the artists who most represent the young people who remain the heart of the revolution are finding new grooves in the present struggles, finding that the messages that helped force Mubarak from power are still as relevant today as they were on February 10, 2011.

As I crossed the Nile to head to the studio with Zine, Essam, and Arabian Knightz to record a new song with producer Taher Saleh, something Alaa Abdel Fattah said a few days before stuck in my head. Criticising the innumerable mainstream Western commentators and scholars who’ve been analysing the importance of social media in the Arab Spring, he explained that “all their analyses remove power from the social media equation. This wasn’t about the revolutionary potential of social media, it was about using it as a tool for propaganda in a struggle against a far more powerful enemy.”

There was no such danger of disempowered art here. Literally as the clock struck midnight, marking the arrival of the third anniversary of Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation two countries to the west, ideas, sounds and styles flew back and forth across the studio’s “live” recording room as musicians from Algeria, Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia and the US were creating precisely the laboratory for artistic and socio-political change about which Zine spoke above. In short, a new weapon in the ongoing propaganda war between the opposition and the emerging power elite was being forged, one that has the added strength of uniting artists from across the Arab world in shared revolutionary solidarity and purpose.

It’s hard to know if or when the sense of purpose and solidarity so easily achieved by musicians can be translated to a broader public beset with much more basic concerns. What is clear is that however much more wealth or ties to power and violence Egypt’s other political contenders possess, the ability to shape powerful political popular culture and physically control revolutionary symbols such as Tahrir Square, will ensure that the revolutionaries will be a force to be reckoned with as Egypt enters the more mature, political phase of their political transformations to post-authoritarian democracies. Ramy Essam put it best as I left him near his tent late one night (as “irhal” blasted through the loudspeakers yet again across the Midan), “As long as Tahrir needs to be occupied, I’ll be here.”

Mark LeVine is professor of Middle Eastern history at UC Irvine and distinguished visiting professor at the Centre for Middle Eastern Studies at Lund University in Sweden and the author of the forthcoming book about the revolutions in the Arab world, The Five Year Old Who Toppled a Pharaoh. His book, Heavy Metal Islam, which focused on ‘rock and resistance and the struggle for soul’ in the evolving music scene of the Middle East and North Africa, was published in 2008.