Where the US and China can agree to agree

China and the US are often viewed as adversarial – but they agree on issues including clean energy and cyber-security.

|

| Iran is currently an important source of oil for China, but Chinese companies want to diversify their supply lines [EPA] |

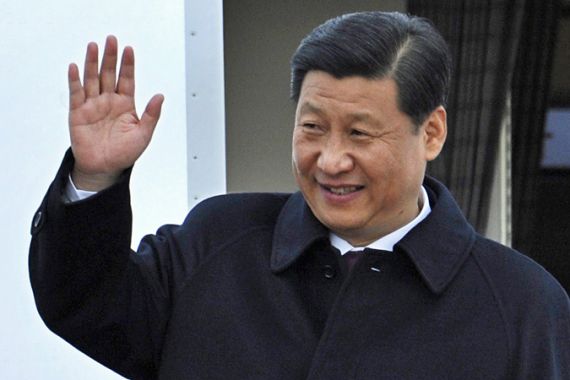

New York, NY – China-US relations may dominate news coverage this week as the country’s presumptive next leader – Xi Jinping – visits the United States. The two countries have conflicting interests and ideologies in currency valuation, military developments in East Asia, and how to deal with the violence in Syria. In an election year, US politicians from both parties can be expected to heighten criticism of China. But as discussions begin between US President Barack Obama and Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping, there are important areas of agreement between the two countries.

| Little-known past of China’s ‘next leader’ |

Differences are real, as should be expected between two large countries with large economies, separated by large differences in development and history. The notion of simple competition between a powerful United States and a rising China, however, does not withstand scrutiny in view of the broad and important areas of agreement and common interest. In an era of global trade and increasingly pervasive digital connectivity, peoples and economies are not so easy to divide along geographic lines.

Three areas of agreement – Iran, clean energy, and cybersecurity – might not get much attention during Xi Jinping’s US tour and the coming political season, but they reveal a change of mindset needed to maintain peaceful ties across the Pacific.

Iran policy

Diplomats from the United States and other NATO countries sharply criticised China and Russia earlier this month for blocking progress on a UN Security Council resolution to address the violence in Syria. China’s stance recalled its long-standing position against violating national sovereignty. But Chinese actions on Iran have revealed significant agreement with countries seeking an end to nuclear development efforts. Perhaps more importantly, some recent Chinese moves send a signal to leaders in Tehran that Iran cannot bet on Chinese support in the face of broad international criticism.

Iran is an important source of oil for China – at least for now. In January, China cut its oil imports from Iran, and Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao made his country’s position on a nuclear Iran perfectly clear: “China adamantly opposes Iran developing and possessing nuclear weapons.” This comes as Chinese oil companies are working hard to diversify their supply lines.

This most recent action comes as part of a pattern of quiet Chinese cooperation with the international community on Iran, according to the progressive Center for American Progress. In 2010, China voted to pass UN Security Council Resolution 1929, which imposed stringent new sanctions on Iran.

For different reasons and in different ways, the United States and China both appear committed to making sure any Iranian nuclear ambitions are thwarted.

Clean energy

For those who follow international climate talks, the United States and China are perennial foes. The smaller, more developed country pushes for strong emissions caps and international monitoring. The larger, less developed country scoffs that the developed world has dumped more than its share of carbon already and argues that its population should not remain poor to atone for the sins of the rich. But that doesn’t mean the countries don’t have anything in common on the environment.

Both countries are investing significant funding in research and development for clean energy technologies. The irony is that each country’s subsidies have been the subject of consternation for the other. Consider two headlines: “US to Investigate China’s Clean Energy Aid,” The New York Times, October 15, 2010; and “China to probe US clean energy subsidies,” The Financial Times, November 25, 2011.

Reporting this tit-for-tat over technicalities as “an escalating trade dispute”, however, misses the message: Two collosal economies in the integrated world trade system are devoting significant resources to developing clean energy technologies. Although those in China’s Ministry of Commerce and the US Trade Representative Office may cry foul, this contest to host innovative, pro-environment technological growth reflects a common interest in a less polluted future.

Cybersecurity

|

“Chinese authorities accuse US representatives of falsely attributing online incursions to Chinese actors, and argue that China too is a target of international hacking.” |

Often regarded as a source of significant friction, or indeed even a potential new “cyber cold war“, cyber-security is nowhere near as clear an issue area as many would have us believe. In fact, the US and Chinese national strategies on the internet are identical in one important way: They are both incoherent, suffering from competing initiatives and interests from different parts of government.

Various members of the US government loudly decry suspected Chinese hacking of government and private-sector systems. Meanwhile, intelligence experts acknowledge that the United States is an avid user of advanced computer spying techniques.

Chinese authorities accuse US representatives of falsely attributing online incursions to Chinese actors, and argue that China too is a target of international hacking. Meanwhile, Chinese military journals describe “integrated network and electronic warfare” and “computer network exploitation” as important elements in a Chinese contest with a superior conventional force, according to a 2009 report.

Agreeing to agree

The US State Department under Hillary Clinton has escalated its efforts to promote internet freedom around the world, but commercial interests (such as those behind SOPA) and security experts promote a less anonymous internet. Less anonymity may increase insitutional security, but it would undermine the technical and legal frameworks that tie online freedom to offline freedom.

Meanwhile, Chinese efforts to maintain stability and stop potential unrest by censoring online content and discourse come alongside the rapid expansion of internet access among the Chinese populace. The growth of the online population in China, which increases with the government’s blessing (and encouragement, if you count the growing state-owned telecommunications companies), is seen by many as a source of development opportunities and advancement for the Chinese people.

From these examples, it is difficult to derive a principled stand on either side. The fact is that the United States and China are both home to avid internet users who want flexibility and security, and both governments want economic and strategic stability. A first step to resolving the appearance of disagreement would be for each country to acknowledge the competing interests at home before pointing fingers abroad.

Each of these issues – Iran sanctions, clean energy subsidies, and cybersecurity – can be seen as a conflict or an area of common interest and experience. The fact that the press and our political leaders give us only the conflict narrative is vexing. Ultimately, people in China, the United States, and the rest of the world must choose whether to see their relations as adversarial or cooperative.

Graham Webster is a public policy and communications officer at the EastWest Institute and an independent analyst on East Asian politics and technology.

Follow him on Twitter: @gwbstr