Race politics in the Hawkeye and Granite States

New Hampshire and Iowa wield so much power and influence, they make a mockery of the US presidential primary process.

|

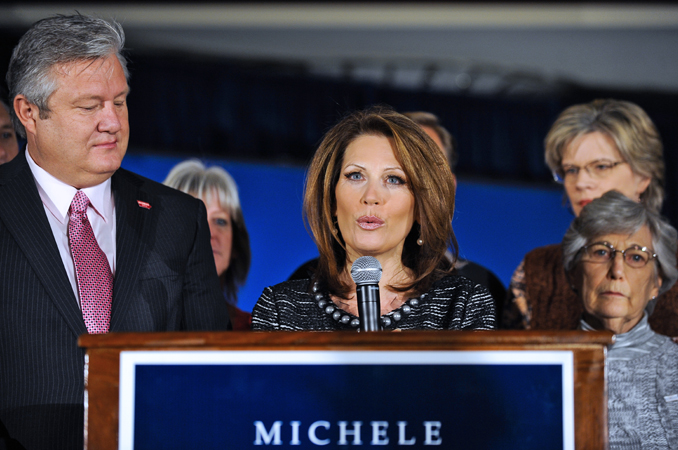

| The Iowa caucus has so much power, Republican presidential candidate Michele Bachmann suspended her bid shortly after results showed her doing poorly in the Hawkeye State [EPA] |

As she covered Iowa’s recent Republican caucus race, Andrea Mitchell of NBC News recently offered the following analysis of the state and its voters: “The rap on Iowa – it doesn’t represent the rest of the country. Too white, too evangelical, too rural.”

Mitchell’s remark swiftly led to criticism from conservative bloggers and cable television commentators alike. Bernard Goldberg of Fox News, for example, told that network’s leading talk show host, Bill O’Reilly, that mainstream media reporters such as Mitchell would never say that “South Carolina is too black”. Blogger Noel Sheppard of Newsbusters, which specialises in “documenting, exposing and neutralising liberal media bias”, attacked NBC as an “Obama-loving” network, and added, “Nice way of the NBC Nightly News informing viewers that much as the media did in 2008, the race card will be played whenever possible to assist Barack Obama in getting re-elected”. And the political website RealClearPolitics.com charged Mitchell with “opining” rather than reporting.

In rejecting the criticism and accusations of editorialising, NBC News spokesperson Erika Masonhall quickly “clarified” Mitchell’s statement, saying the reporter had merely been “referencing critics who argue that the state shouldn’t carry so much weight because it doesn’t proportionally represent the rest of the country”. Masonhall noted that Mitchell had also interviewed “analysts and Iowa voters who explain why the state is so important in the election cycle”.

Unequal representation

|

“That’s about 20 per cent of Iowa’s registered Republicans, four per cent of the population of Iowa, and .04 per cent of the total US population.“ – Brian Montopoli, CBS News |

But why were Mitchell’s remarks even controversial? After all, both she and the unnamed critics she was “referencing” were right: neither Iowa with its bizarre caucuses nor its first-in-the-nation primary cousin New Hampshire accurately reflect the overall electorate of the United States. The real controversy should be about why the recent “overhyped, unrepresentative Iowa caucuses” (as Brian Montopoli of CBS News described them), along with the equally overhyped and unrepresentative New Hampshire primary, continue to be “so important in the election cycle”. After all, taken together, residents of the two states make up less than two per cent of the population of the US. What’s worse, only about 120,000 of them even participate in the Iowa Republican caucuses, (“That’s about 20 per cent of Iowa’s registered Republicans, four per cent of the population of Iowa, and .04 per cent of the total US population,” as Montopoli points out) and only about twice as many will vote in the upcoming New Hampshire Republican primary.

Taken together, the relatively few caucus and primary voters in these two small states are about as far from a representative sample of the US population as possible. Iowa caucus-goers, for example, are overwhelmingly white, well educated, highly conservative and very religious. (On the Republican side, 60 per cent identified as “born-again” or “evangelical” Christians in 2008.) Iowa is also much more rural than most of the US, and its unemployment rate is well below that of the national norm. Add in the facts that, thanks to the caucuses, Iowa farmers help to determine much of the US’ food, farm and energy policies, and that its caucuses tend to favour the involvement of committed party activists, and you end up with a process that skews entire elections in a more racial, rural, religious and conservative direction than the rest of the voters in the US want to head.

Much the same holds true of New Hampshire, where the nation’s first actual primary election follows closely on the heels of the Iowa caucuses. The Granite State’s minuscule population of 1.3 million is even whiter (94 per cent) than that of Iowa; its largest city, Manchester, has little more than 100,000 residents; and its unemployment rate is even lower than that of Iowa, for example.

| Inside Story US 2012: Does Romney’s Iowa win really matter? |

In addition, the fact that past winners in both Iowa and New Hampshire have had mixed success in getting their party’s nomination raises further questions about the relevance of the results there. Both Democrats and Republicans, from Edmund Muskie in 1972 to Mike Huckabee in 2008, have won in Iowa, but lost their party’s nomination. George HW Bush even managed to win Iowa, but failed to become the party standard-bearer in 1980 – and then to lose Iowa while winning not only the Republican nomination, but also the presidency in 1988.

In New Hampshire, John McCain won the Republican primary in 2000, but lost the party’s nomination to George W Bush. More recently, Hillary Clinton won the Democratic primary in 2008, but the party eventually chose Barack Obama. Conversely, Democrat Walter Mondale in 1984 and Republicans Bob Dole in 1996 and George W Bush in 2000 all lost New Hampshire, but eventually won their party nomination. In fact, since 1984, only two candidates have won both the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primaries. If current frontrunner Mitt Romney follows his eight-vote victory in Iowa with a win in New Hampshire, he will be the first non-incumbent Republican to win both states since the 1970s.

‘Tiny and distinct’

|

“Every four years, two tiny and distinct groups of people get to set the policy agenda for the most powerful country on Earth.“ – Rory O’Connor |

Every four years, two tiny and distinct groups of people get to set the policy agenda for the most powerful country on Earth. They wield their extraordinary and disproportionate influence, thanks in large measure to the very same media outlets (including NBC News, of course) that focus so intently on their first-in-the-nation position. Defenders of the two states’ special status like to hail the “retail” or “personal” style of politics supposedly found uniquely in Iowa and New Hampshire, which reputedly enables voters to assess candidates in a way the rest of the populace can’t. But that argument is harder than ever to make in an age when television reigns supreme, with multiple cable debates and millions of dollars in unregulated advertising now setting the agenda.

New Hampshire and Iowa fiercely protect their first place status in the voting process; in fact, they ensure it with laws mandating that their contests take place before those of any other state. The Iowa caucus, however, is really nothing more than a non-binding popularity contest, which does little to determine which candidates actually win the state’s delegates to the Republican nominating convention. Still, the intense focus the media place on covering Iowa’s and New Hampshire’s “horse races” diverts attention from issues and forces candidates to spend months and millions winning just a few thousand votes in places like Iowa – home, as one critic phrased it, “to more pigs than people”. Moreover, the people who do live there simply don’t reflect the general population of the US. Iowans are 91.5 per cent white, for example, compared with about 67 per cent of all Americans. Hispanics are now 14.4 per cent of the national population, but only 3.7 per cent in Iowa, and the state is only 2.3 per cent African-American, compared with 12.8 per cent nationwide.

Iowa and New Hampshire have long been first on the national electoral calendar. New Hampshire’s primary was the first test for presidential hopefuls before the date of Iowa caucuses was moved up in 1972. It became known for political upsets when Dwight Eisenhower defeated his Republican rival Senator Robert Taft in 1952 before winning the presidency. Historically, Iowa held its caucus in mid-February, followed a week later by a primary in New Hampshire; the campaign season then ran through early June, when primaries were held in such large population states as New Jersey and California. Winning in either state – or at least doing better than expected – could put a campaign on the map, and doing poorly often led candidates to pull out. Some spent years organising support in these states. In 1976, the relatively unknown governor of Georgia, Jimmy Carter, followed such a strategy all the way to the Democratic nomination and later the presidency.

Fearing that Iowa and New Hampshire were exerting too much influence in the nomination process, however, other states soon began scheduling their primaries earlier. In 1988, for example, 16 mostly Southern states moved to early March. Such “front-loading” escalated during the 1990s, and Iowa and New Hampshire then scheduled their contests even earlier. By 2008, 40 states set primaries or caucuses for January or February; several even attempted to blunt the influence of the two early states by moving to early January. This required all the candidates to raise more money sooner, while simultaneously making it more difficult for lesser-known candidates to gain momentum by doing well in the early going.

The unrepresentative slice

Why should you care that the influence of these two small and unrepresentative states grows with each election? The Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primaries not only help select who runs for president in the general election, but they also have a huge impact on what the two major parties come to stand for, and thus how they govern. Their rising importance is owed to two separate, but related phenomena we can already see in action: momentum and elimination.

Here’s how it works: candidates who beat expectations in these early voting states are seen as having momentum, and thus gain more attention amid raising expectations and are taken more seriously by financial contributors, media – and eventually by voters themselves. For those with little momentum, the opposite is true; they lose attention, expectations decline, funding dries up and the media turns away. A case in point: Michele Bachmann, who, according to media reports “affirmed her status as a top-tier candidate in the Republican race to challenge President Obama in 2012” in August 2011 when she won a pre-caucus “straw poll” in Iowa by receiving 4,823 votes of the nearly 17,000 votes cast. A few months later, Bachmann came in last in the caucuses and was forced to withdraw from the presidential race.

|

“The fact that Iowa and New Hampshire still have so much power and influence makes a mockery of the entire US presidential primary process.” – Rory O’Connor |

The fact that Iowa and New Hampshire still have so much power and influence makes a mockery of the entire US presidential primary process. Many reformers now call for either a series of regional primaries or just one wide open national primary that would give every state equal status. But all agree that the current primary system is obsolete and puts too much power in the hands of too few.

It seems obvious that every US voter – and not just those few voting in Iowa and New Hampshire – should have a chance to help decide which politicians and policies will govern us. But will things change? Probably not, for two reasons. The first is nature of the US political system itself – but the second problem is with its media system. Whatever happens in the truncated and frenetic 2012 campaign – and no matter how many complaints are aired about the process – the odds remain high that Andrea Mitchell and the rest of her mainstream buddies will find themselves back in Iowa and New Hampshire four years from now for yet another round of horse race coverage focused once again on a narrow, unrepresentative slice of citizens.

Author, blogger, filmmaker and journalist Rory O’Connor is co-founder and president of the international media firm Globalvision, Inc, and Board Chair of The Global Centre, an affiliated non-profit foundation. O’Connor has directed, written and/or produced hundreds of television programmes and films, and served as executive in charge of two award-winning broadcast news magazines, South Africa Now and Rights & Wrongs: Human Rights Television. His articles have appeared in many leading periodicals, he is the author of three books, and he also regularly posts on his popular “Media Is A Plural” blog as well as on such leading websites as the Huffington Post and AlterNet.

Follow him on Twitter: @rocglobal

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.