A jurisprudence of conscience

An international double standard is dividing the international community between the victorious and the defeated.

|

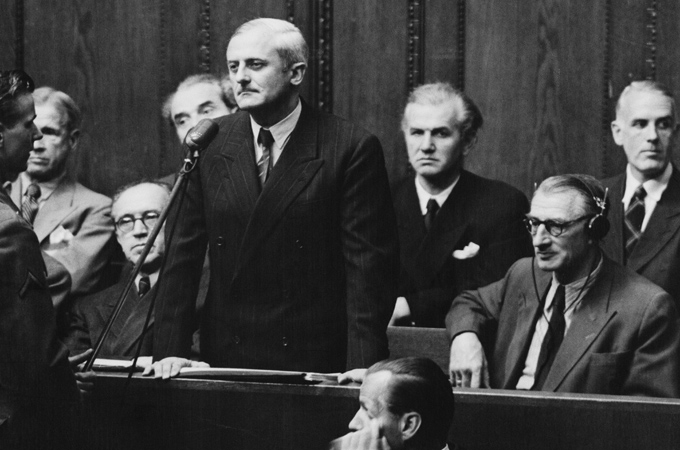

| The Nurenberg trials allowed the US to try germans without reflecting on their own warfare [GALLO/GETTY] |

Montreal, Canada – Ever since German and Japanese surviving leaders were prosecuted after World War II at Nuremberg and Tokyo, there has been a wide abyss separating the drive for criminal accountability on the part of those who commit crimes against peace, crimes against humanity, war crimes from the realities of world politics. The law pushes toward consistency of application, with the greatest importance attached to holding accountable those with the greatest power and wealth.

The realities of world politics move in the opposite direction, exempting those political actors that play dominant roles. In a sense the pattern was encoded into the seminal undertakings at Nuremberg and Tokyo in the form of “victors’ justice”. Surely, the indiscriminate bombings of German and Japanese cities by Allied bomber fleets and the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were ‘crimes’ that should have been punished if the tribunals had been fully ‘legal’ in their operations.

It was the case, especially in Tokyo, that the tribunal allowed defendants to be represented by competent lawyers and that the judges assessed fairly the evidence alleging criminality, producing dissenting opinions in the Japanese proceedings and an acquittal at Nuremberg. In effect, there was a measure of procedural fairness in these trials in the sense that those accused did engage in activity that it was legally desirable to criminalise through findings of guilt and impositions of punishment.

|

“The strong do what they will, the weak do what they must.” |

There was a second message arising from these trials: that winning carries with it the opportunity to reinforce the justice of history by pronouncing of the criminality of losers while overlooking the criminality of victors. And then there was a third message that has been called ‘the Nuremberg promise’, which involves a commitment in the future to abide by the norms and procedures used to punish the German and Japanese surviving military and political leaders. In effect, to convert this enactment of victors’ justice into real justice by making criminal accountability a matter of law rather than a reflection of the outcomes of war or a reflection of geopolitical hierarchy.

The Chief Prosecutor at Nuremberg, Justice Robert Jackson (excused temporarily from serving as a member of the US Supreme Court), gave this promise an enduring formulation in an official statement in the court: “If certain acts and violations of treaties are crimes, they are crimes whether the United States does them or whether Germany does them. We are not prepared to lay down a rule of criminal conduct against others which we would not be willing to have invoked against us.” These words have been repeatedly invoked by peace activists, but political leaders take no notice, and the crimes by the powerful keep happening. In imitation of this flawed Nuremberg precedent. Since the end of the Cold War implementation of criminal responsibility has been resumed for losers in world politics, including such leaders as Milosevic, Saddam Hussein and Gaddafi, each of whom were deposed by Western military force.

Double standards

This dual pattern of criminal accountability that cannot be reconciled with law or legitimacy has given rise to several reformist efforts. Civil society and some governments have favoured a more genuine legalisation of criminal accountability and raised liberal hopes by unexpectedly achieving the establishment of the International Criminal Court in 2002. Yet this and other formal initiative have not displaced the realities of world politics, which continue to exhibit the Melian ethos when it comes to criminal accountability: “the strong do what they will, the weak do what they must”. Double standards persist: the evildoers in Africa are targets of prosecutors, but those in the West that wage aggressive war or embrace torture as national policies continue to enjoy impunity, or almost so.

The existence of double standards is part of the deep structure of world politics. It is even given constitutional status by being written into the Charter of the United Nations by allowing the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, that is the winners in 1945, to exercise a veto over any decision affecting the peace and security of the world, thereby exempting the world’s most dangerous states, being the most militarily powerful and expansionist, from any obligation to uphold international law. Such a veto power, while sounding the death knell for the UN in its core role of war prevention based on law rather than geopolitics, is probably responsible for keeping the Organisation together through times of intense geopolitical conflict.

Without the veto, undoubtedly the West would have pushed the Soviet Union and China out the door during the Cold War years, and the UN would have disintegrated in the manner of the League of Nations, which after the end of World War I converted Woodrow Wilson’s dream into a nightmare. Beyond this, even seen through a geopolitical optic, the anachronistic character of the West-centric Security Council is a remnant of the colonial era. 2011 is not 1945, but the rigidity of the Organisation means that India, Brazil, Turkey, Indonesia and South Africa seem destined to remain permanent ladies in waiting as the UN goes about its serious male business. What this means, bearing on the politics of individual criminal accountability, is that all that is ‘legal’ is not necessarily ‘legitimate.’

My argument seeks to make two main points: first, double standards pervade the application of international criminal law eroding its authority and legitimacy; and secondly, those geopolitical hierarchies embedded in the UN framework lose their authority and legitimacy by not adapting to changing times and conditions, especially the collapse of the colonial order and the rise of non-Western centres of soft and hard power.

|

“Also ignored by critics was the fact that only such initiatives could overcome the blackout of truth achieved by the geopolitics of impunity.“ – Richard Falk |

There are different kinds of efforts to close this gap between the legal and the legitimate in relation to the criminality of political leaders and military commanders. One move is at the level of the sovereign state, which is to encourage the domestic criminal law to extend its reach to cover international crimes. Such authority is known as Universal Jurisdiction (UJ), a hallowed effort by states to overcome the enforcement weaknesses of international law, initially developed to deal with the crime of piracy, interpreted as a crime against the whole world. Many liberal democracies in particular have regarded themselves as agents of the international legal order, endowing their judicial system with the authority to apprehend and prosecute those viewed as criminally responsible for crimes of state. The legislating of UJ represented a strong tendency during the latter half of the twentieth century in the liberal democracies, especially in Western Europe. This development reached public awareness in relation to the dramatic 1998 detention in Britain of Augusto Pinochet, former ruler of Chile, in response to an extradition request from Spain where criminal charges had been judicially approved. The ambit of UJ is wider than its formal implementation as its mere threat is intimidating, leading those prominent individuals who might be detained and charged to avoid visits to countries where such claims might be plausibly made. As might be expected, UJ gave rise to a vigorous geopolitical campaign of pushback, especially by the governments of the United States and Israel reacted with most fear to this prospect of criminal apprehension by foreign national courts. As a result of intense pressures, several of the European UJ states have rolled back their legislation so as to calm the worries of travellers with tainted records of public service!

There is another approach to spreading the net of criminal accountability that has been taken, remains controversial, and yet seems responsive to the current global atmosphere of populist discontent. It involves claims by civil society, by the peoples of the world, to establish institutions and procedures designed to close the gap between law and legitimacy in relation to the application of international criminal law. Such initiatives are appropriately traced back to the 1966-67 establishment of the Bertrand Russell International Criminal Tribunal that examined charges of aggression and war crimes associated with the American role in the Vietnam War. The charges were weighed by a distinguished jury composed of moral and cultural authority figures chaired by Jean-Paul Sartre.

The Russell Tribunal was derided at the time as a ‘kangaroo court’ or a ‘circus’ because its conclusions could be accurately anticipated in advance, its authority was self-proclaimed and without governmental approval, it had no control over those accused, and its capabilities fell far short of enforcement. What was overlooked in such criticism was the degree to which this dismissal of the Russell experiment reflected the monopolistic and self-serving claims of the state and state system to control the administration of law, ignoring the contrary claims of society to have law administered fairly in accord with justice, at least symbolically. Also ignored by critics was the fact that only such initiatives could overcome the blackout of truth achieved by the geopolitics of impunity.

No exemptions

The Russell Tribunal may not have been ‘legal’ as understood from conventional governmental perspectives, but it was ‘legitimate’ in responding to double standards, by calling attention to massive crimes and dangerous criminals who otherwise enjoy a free pass, and by providing a reliable and comprehensive narrative account of criminal patterns of wrongdoing that destroy or disrupt the lives of entire societies and millions of people. As it happens, these societal initiatives require a great effort, and only occur where the criminality seems severe and extreme, and where a geopolitical mobilisation precludes inquiry by established institutions of criminal law.

It is against this background that we understand a steady stream of initiatives that build upon the Russell experience. Starting in 1979, the Basso Foundation in Rome sponsored a series of such proceedings under the rubric of the Permanent Peoples Tribunal that explored a wide variety of unattended criminal wrongs, including dispossession of indigenous peoples, the Marcos dictatorship, Armenian massacres, self-determination claims of oppressed peoples. In 2005 the Istanbul World Tribunal on Iraq inquired into the claims of aggression, crimes against humanity and war crimes associated with the US/UK invasion and occupation of Iraq, commencing in 2003, causing as many as one million Iraqis to lose their lives, and several million to be permanently displaced from home and country. In the last several weeks the Russell Tribunal on Palestine, a direct institutional descendant of the original undertaking, held a session in South Africa to investigate charges of apartheid, as a crime against humanity, being made against Israel. In a few days, the Kuala Lumpur War Crimes Tribunal will launch an inquiry into charges of criminality made against George W. Bush and Tony Blair for their roles in planning, initiating, and prosecuting the Iraq War, to be followed a year later by a subsequent inquiry into torture charges made against Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld and Alberto Gonzales. I intend to write subsequently about each of these proceedings.

Without doubt such societal efforts to bring at large war criminals to symbolic justice is consistent with the growing demand around the world for real democracy upheld by a rule of law that does not exempt from responsibility the rich and powerful.

Richard Falk is Albert G. Milbank Professor Emeritus of International Law at Princeton University and Visiting Distinguished Professor in Global and International Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He has authored and edited numerous publications spanning a period of five decades, most recently editing the volume, International Law and the Third World: Reshaping Justice (Routledge, 2008).

He is currently serving his third year of a six year term as a United Nations Special Rapporteur on Palestinian human rights.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.