Ritual in the revolution?

Chanting and dancing are more vital for political protest than information technologies and social media, says scholar.

|

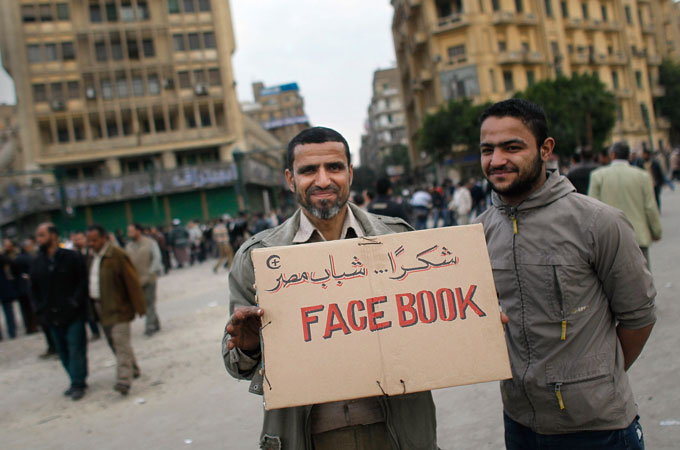

| Facebook has been one of many tools used to mobilise people during the Arab Spring, however people en masse is what gave people their strength to protest, not Social Media alone [GALLO/GETTY] |

The hype in the West over ‘social media’ and the Arab Spring is becoming unbearable. It’s as if revolution and effective political protest were impossible until Facebook and mobile telephony came along.

Think tanks, universities, academic associations and NGOs are all jumping on the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) bandwagon. Their tag lines ring with happy liberal slogans about inclusion, peaceful change, and high principle.

One outfit is even considering whether ICTs take us “beyond revolution”, transforming the very nature of politics and governance.

Needless to say, transformations in communications technology are always significant and demand careful analysis. But it is worth asking why the hype and what is being obscured by it?

Turning the Arab Spring into a conversation about ICTs has inexhaustible political utility for the West. For one thing, there are the conversations that are not happening while all these academics and research centres debate the wonders of the internet.

First and foremost is the central responsibility of the Western powers not only for maintaining repressive regimes in power, but in many cases for setting them up in the first place. For how many decades have Western powers provided direct military and policy assistance to regimes that locked up, tortured and shot their own people, in and beyond the Arab world?

British intelligence was working closely with Libyan security services right up until the Royal Air Force started bombing Libya.

Conversations of this kind quickly lead to considerations of political and legal responsibility of Western officials. They may even take us ‘beyond’ such matters to those of financial reparation and the deeper responsibility of the West for the stolen wealth of the non-European world. It was precisely to steal such wealth that repressive regimes were supported.

One can see why talking about ICTs is less jarring to Western ears, especially those of the private and public donors who support so much of the research that occurs in universities and think tanks.

Obfuscating Western responsibility is only the beginning. The hype over ICTs and social media goes much further. It appropriates to the West – its products and technologies – the agency for the revolution. It was Western technology and Western political ideas that liberated the Arabs!

The elementary fact that the Arab Spring was brought about by ordinary people risking life and limb recedes into the background. Not only is their agency erased by the hype over ICTs, but what they fought for – political participation – also is assumed to be somehow ‘Western’.

How do ordinary people do it? They have been protesting and revolting around the world for centuries, long before mobile telephony came about.

A key is found in one of the things people use ICTs for: to organise meetings and demonstrations. As any activist or union organiser can tell you, the people are stronger when they come together, when they feel themselves in unison.

Each and every revolt in the Arab Spring, and every popular revolution that has ever happened, involves the power of the people in a very literal sense. The people assemble as a body, in demonstrations large and small.

Only once the people have assembled, and felt their own power, can they contemplate the all too evident costs of insurrection with any hope of success.

Such assemblies make use of some of the oldest and most basic forms of human sociability. Keeping together in time, people sing, chant slogans and dance. Their bodies touch and heave and give voice as one. They manage to convince themselves they can do anything, even hurl themselves upon the regime’s bayonets, as long as they stay together.

Such rituals are not the preserve of primitive tribes. They lie behind the ability of human beings to form social groups, to sink their individual identity into a larger collective. Armies use such rituals, in the form of drill, to create esprit de corps. Sports teams and their fans partake in them. Corporations try to use them to inspire their employees. They are absolutely essential to collective political action of any kind.

Once formed, such groups exhibit a remarkable characteristic. If one of their members is killed, the life force of the deceased pulsates through the survivors, bringing them all closer together, increasing their power, their cohesion, their unity. Anyone who has attended a funeral will have felt such forces, which the original Australians called mana.

The death of one, of two, of ten, of even one hundred, can make the people stronger. Truly are such rituals weapons with which one can make revolution.

Tarak Barkawi is Senior Lecturer in the Centre of International Studies, University of Cambridge

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.