Iran: Ahmadinejad vs Khamenei

Does Ahmadinejad’s fall empower or hurt the West in its troubled relationship with the Islamic republic?

|

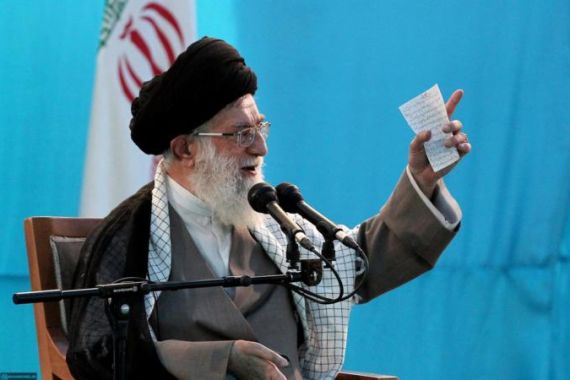

| Ahmadinejad has found himself in the company of past Iranian presidents who have been marginalised [REUTERS] |

Few could have imagined two years ago that the man who caused a Tehran spring that nearly brought down the Iranian regime, only for it to be saved by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, would today be reduced to political impotence. But after a three-month conflict, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad should be grateful Khamenei has not ordered his arrest, and, at least for now, is content for him to serve out his term as a lame duck.

As this battle has unfolded, important lessons about the workings and dysfunction of the Iranian political and theological system have emerged.

The limits of presidential power

Like the two presidents before him, Ahmadinejad made the mistake of assuming Iranian presidents have power. He also incorrectly assumed that, because of his once special relationship with Khamenei, who had placed his full weight and legitimacy behind Ahmadinejad when it appeared his re-election in June 2009 was rigged, he could exploit his position to appoint his loyalists to key political posts – while dismissing others he deemed to be his foes.

The limits of clerical support

No matter how much some clerics in the past supported Ahmadinejad, once Khamenei made clear his decision to effectively strip the president of his powers, the clergy placed their full support behind the supreme leader. Even Ayatollah Muhammad Taghi Yazdi, the president’s religious mentor, publicly turned against him. Some Iran experts have written that the battle is over divergent interpretations of Shia theology. This is placing a sophisticated mask over what is really a dirty and raw political struggle. In fact, the battle between the president’s faction and loyalists supporting the supreme leader is a conflict between two visions for the Islamic Republic: the supreme leader’s vision, in which the ideal is nothing more than the preservation of the status quo, and Ahmadinejad’s vision, in which clerical rule is marginalised in favour of nationalism and populist religious fervour.

Supporters of the supreme leader maintain that they are defending the Islamic Republic from a “deviant” movement, which seeks to do away with the traditional structures of clerical rule. Ahmadinejad’s opponents may not be far off the mark. The president’s closest confidant and adviser, Esfandiar Rahim-Mashaei, has repeatedly made statements hinting at his disregard for traditional Shia jurisprudence.

The limits of Khamenei’s tolerance

Simply put, Khamenei could not permit a president to defy his orders, make political appointments unilaterally without the consent of various ministries, and pout at home for 11 days in a disappearing act to demonstrate his anger at the supreme leader. Ahmadinejad wanted to build his own network in key ministries that would be loyal only to him, not to Khamenei, in order to ensure the election of candidates belonging to his political faction when parliamentary and presidential polls are held in 2012 and 2013, respectively. Ahmadinejad was grooming Mashaei as his replacement, despite the loathing directed at him by the clerical establishment. According to high-level sources in Tehran, Mashaei may soon follow in the long line of Ahmadinejad loyalists who have been arrested.

The fickle whims of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard

While there is ample evidence to suggest that Ahmadinejad has support within the IRGC – some commanders openly endorsed his candidacy in 2009 – they did not step in to save him. In fact, former commanders in key political posts, such as Tehran mayor Mohammad Qalibaf, have sided openly with Khamenei in the dispute.

Regime above all else

As the points listed above show, what matters most to political elites governing the Islamic republic is regime survival. Ahmadinejad became a threat to this survival. He challenged the authority and legitimacy of supreme clerical rule, and he cast doubt on the divine attributes of the clergy – without which the Islamic republic could not exist in anything like its present form. Whether he is allowed to finish out his term is still in question. As one political adviser said in Tehran: “Ahmadinejad is a knife in Khamenei’s side. Removing the knife will cause a lot of bleeding, but if the pain becomes too much, the knife will be pulled out.”

Ahmadinejad’s fall lends credibility to the “Green movement”, which told Khamenei and all Iranians that he was trouble from the start. In fact, if Khamenei allows him to finish out his term, he should thank the Greens; removing Ahmadinejad would give the opposition a big boost in society, which has grown weary of Ahamadinejad.

The question that has been asked repeatedly is: “What does all this mean for the United States and other Western governments. Does Ahmadinejad’s fall empower or hurt the West in its troubled relationship with the Islamic republic?”

It makes little difference, despite conventional wisdom to the contrary. The argument has been made that Ahmadinejad and Mashaei were the best hope for engagement with the United States, a compromise on the nuclear issue, or both. However, when the president appeared last year to be encouraging a compromise with the 5+1 permanent members of the UN Security Council on Iran’s nuclear programme, this was purely for political gain inside Iran. The president never had any particular conviction to engage the United States or to improve relations with the West unless there were a domestic political reward. Once it became clear that there was no consensus within the inner circle around Khamenei for a deal on the nuclear programme, Ahmadinejad abandoned this goal, even though it would have made him popular within Iranian society. According to many opinion polls, Iranians favour better relations with the United States and Western countries.

Ahmadinejad’s shift in fortune from an insider at the heart of the inner circle around Khamenei to a pariah has been shocking. While protesters – who on one day in June 2009 numbered 3 million – disputed the election results, Khamenei insisted that Ahmadinejad had won fairly, thus casting the enormous power and weight of the post of supreme leader into the contest between demonstrators and the president. This move marked a step away from the traditionally aloof and unifying role the supreme leader had previously assumed, and indicated that Khamenei had firmly cast his lot with Ahmadinejad. But no more.

Ahmadinejad has now found himself in the company of previous Iranian presidents who have been marginalised or sidelined, such as the impeachment of the Islamic Republic’s first president, Abulhassan Banisadr, a longtime critic of clerical involvement in politics. He was impeached in 1981 at the behest of Ayatollah Khomeini, the leader of the Islamic revolution – and Khamenei’s predecessor – for acting against the influence of Iran’s clerics. Similarly, reformist president Mohammad Khatami, who many hoped would open up Iran’s political and social atmosphere, was soon reduced, by the rest of the establishment, to wielding only very limited power.

The paradox of the Ahmadinejad story is that, now, in the eyes of Khamenei, he appears to pose more of a threat to the survival of the regime than the Green movement, whose members have been arrested, tortured, and even killed – all to install Ahmadinejad as Iran’s president.

Geneive Abdo is the director of the Iran programme at The Century Foundation and the National Security Network, two Washington-based think tanks. Shayan Ghajar, a research associate for the programme, contributed to this article.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.