The savvy startup founder who helps Kashmiris overcome crackdown

Javid Parsa, a young restauranteur, uses his social media stardom to connect Kashmiris and get medicine to patients.

New Delhi, India – Javid Parsa, a 31-year-old restauranteur and social media star who was born Bandipora, a picturesque district in Indian-administered Kashmir, is the epitome of a startup founder.

On his feed, he can usually be seen smiling and talking to his cooks or pictured in selfies with customers.

A former Amazon employee and MBA graduate, with about 30,000 followers on social media, he quit a corporate job in Hyderabad in 2014 to return to Kashmir and set up a chain of street food restaurants – Parsa’s.

“I wanted to connect with different people and to me, opening a restaurant was the best way I could do it.”

As a child, he would go to a kandur waan, or traditional Kashmiri baker, with his grandfather and watch as people chatted about politics, religion and society.

“It used to be like a community discussion and I wanted to replicate this sort of a model.”

But since August 5, the day India revoked some of Kashmir’s autonomy, his daily life has taken a turn amid a widespread crackdown.

For more than a month now, his restaurants have remained closed – like most other businesses in the region.

After revoking Article 370, public transport was halted in Kashmir, communication lines including the phone and internet were closed, and thousands of extra troops were deployed on the streets.

We have no choice but to help each other. We are a land of orphans right now.

India has said its aim was to boost security and that communication lines have now been restored.

Some sections of India’s media and the political class claim a sense of “normalcy” has returned to the region.

But Parsa is among the many Kashmiris who disagree.

While some landlines have been restored, the internet is still not working at full capacity and several Kashmiris have not been able to speak to family members in other countries, or in India, since August 5.

By the time of publishing, Al Jazeera was still unable to communicate with freelance reporters in Kashmir via WhatsApp.

There is a shortage of medicine in the valley.

And local journalists cannot report without their proper tools and against the backdrop of alleged intimidation.

These days, Parsa, currently in India, uses his internet stardom to help people connect.

His social media feeds are full of posts with a red background and a #KashmirSOS hashtag, calling on people to help each other – in practical ways.

He has built a network by connecting relatives who have lost contact with one another, crowdfund several thousand dollars for a needy family, and get medicine – and even blood – to patients.

“We have no choice but to help each other. We are a land of orphans right now,” he told Al Jazeera.

‘I must have connected at least 1,500 calls’

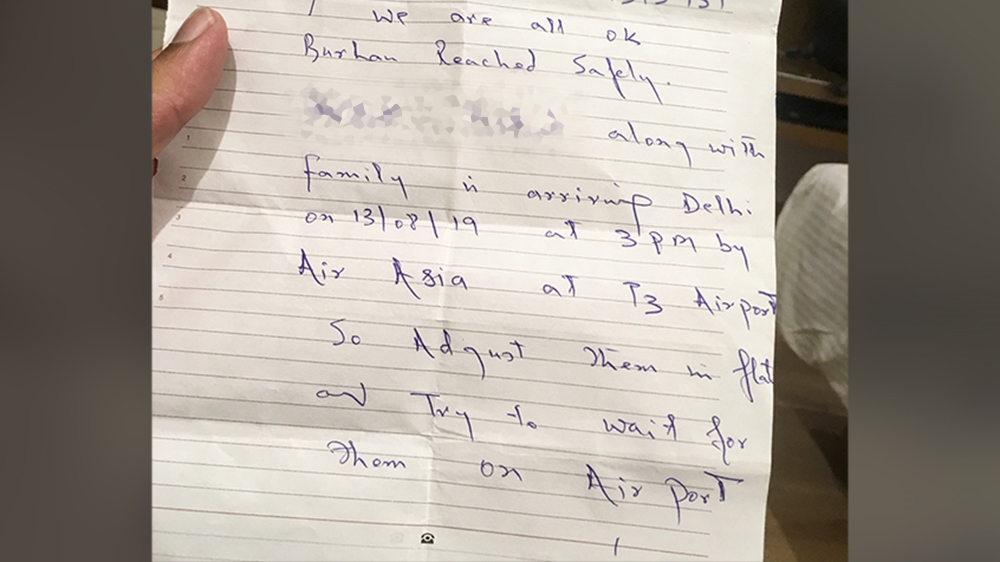

Parsa said he has connected hundreds of Kashmiri families with their relatives abroad, either by phone or sending letters with people who are able to travel, often international journalists.

When Parsa was able to travel himself, he took 14 letters from Kashmiris to their loved ones with him.

“It wasn’t completely intentional in the beginning,” he said of his new charitable role.

“Prior to the communication blockade, I had already booked a flight to New Delhi for a business meeting and planned to come back home to celebrate Eid.

“But within half an hour of landing, I got so many calls from people [living outside the valley] inquiring about the wellbeing of their families, that I decided to stay back and do something to connect people.”

Until recently, most operational phones were at police stations, government offices, and just a few private residences. But these landlines did not have international dialling, so people would call Parsa, and he would connect them to their relatives through conference calls.

“I would ask them to call me at a particular time as I would already be on the call, with the other side,” he said, adding that on a busy day, he would hold at least 50 calls a day.

“From August 12, I must have connected at least 1,500 calls,” he said.

In today's age of the internet, this is not a mere communication blockade but 'bio-political' control - control over both bodies and politics.

Most of these were made to people performing Hajj in Saudi Arabia and Kashmiri medical students studying outside India, in Bangladesh, Kyrgyzstan and Russia.

“I am surprised how my contact number reached [so many people] in Kashmir, since there was hardly any means of communication,” he said.

“But I think it got disseminated through these contact points, where the landlines were working. People would perhaps get to know at these booths that there was some guy in Delhi who would connect you with relatives staying abroad.”

Hundreds of people, for instance, called Parsa from the Kupwara Grand Resort, a hotel.

“Each day, up to 20 people call Javid from this place, so that they could talk to their loved ones living outside Kashmir,” the owner told Al Jazeera.

Parsa’s brother himself, based in Kashmir, travels some five kilometres every day to call his sibling.

Commenting on the communications crackdown, Gowhar Farooq, assistant professor at AJK Mass Communication Research Centre in New Delhi, told Al Jazeera: “In today’s age of the internet, this is not a mere communication blockade but ‘bio-political’ control – control over both bodies and politics.

“If a patient has to be taken to a hospital, the ambulance has to be called by phone. When you deny this, you are directly denying an individual’s right to live.”

He said the move to limit access to the internet and phone lines impacted Kashmiris’ physical being, meaning the region has been made into an “enclosure”.

“The government controls air space and land,” he said. “Communication provided some sort of mobility and that little window has also been seized.”

Overcoming the medicine shortage

In terms of healthcare, given the shortage of medicine, Parsa has received medical donations to deliver to Kashmiri families.

“I got calls from international numbers. People who could afford medicines but didn’t have a medium to send those,” he said.

“So, they sent me medicine to my outlet at Delhi where I used to store them, and then people going to Kashmir volunteered to dispatch them back home.”

Last year, Parsa raised funds for a cancer patient named Younis.

Now, said Parsa, “Younis collects a list of patients who need life-saving medicine in Kashmir, travels to Delhi, buys those medicines from his own pocket and then goes back and delivers them in Kashmir.”

As his phone and email are inundated with messages, Parsa reflects on a particularly memorable case.

A family’s house burned down during the crackdown and they could not call the emergency services.

“I read the news online about the fire incident at Aloochi Bagh (a locality in downtown Srinagar), which happened just a few months before their two daughters were set to be married,” he said.

Because most businesses were closed, Kashmiris could not be asked for charity since their salaries were delayed.

“So, I posted on the internet and started a fundraiser,” said Parsa. “So far, we have been able to generate 500,000 INR (about $7,000) – most of which was contributed by Kashmiri students, corporates and businessmen living outside valley.”