Russia’s elections: ‘Unprecedented fight for turnout’

Is Vladimir Putin tired of the electoral game? And is he anxious about a low turnout?

Moscow, Russia – On March 18, Russians will head to the polls to vote in the seventh presidential election since the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991.

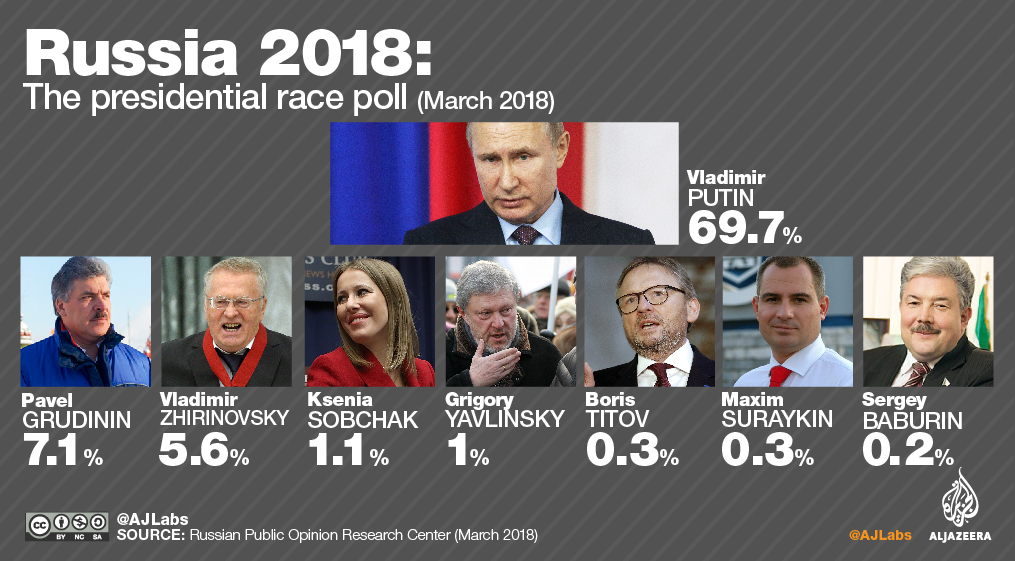

Eight candidates are running in the race, including the incumbent president, Vladimir Putin, who seems poised to win his fourth term in the Kremlin.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsPutin: Concert hall shooting is act of intimidation by Kyiv

How will the Moscow concert hall attack affect Putin?

Moscow theatre attack suspects show signs of beating in court

While the Russian president is currently facing a diplomatic crisis abroad, with the UK expelling 23 Russian diplomats over a nerve agent attack against a former spy, at home he enjoys solid support.

Around 69 percent of respondents in a March 9 survey released by state-run Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VCIOM) said they would vote for him.

The polls reflect not only his consistently high approval ratings but also the absence of tough competition from the other candidates, as the main challenger, Alexei Navalny, was disqualified by the Central Electoral Commission (CEC) in December.

None of the other seven candidates – two of whom are veterans in running in presidential elections – have gotten more than eight percent in recent surveys conducted by the VCIOM.

With the outcome of the elections widely perceived to be in his favour, the incumbent president has led a rather modest campaign.

But he has faced a call for an election boycott from part of the opposition and the possibility of a lower turnout, which has sent authorities scrambling to mobilise the electorate.

Crimea and low expectations

Last year, Putin delayed announcing his intention to run for re-election, raising speculations about whether he has the energy to complete a fourth term.

He only confirmed his re-election bid less than two weeks before the start of the official campaign period on December 18. Abbas Gallyamov, a political analyst, says Putin is “tired” of dealing with domestic politics.

“The challenges he faces, they are hard to deal with. The deteriorating economy – it’s just dying and he doesn’t know how to [fix] it. All this corruption – he would like it to disappear but it doesn’t and he doesn’t know what to do about it,” said Gallyamov, who used to work as a speech writer for the Putin administration in the 2000s. “It gives him the feeling of weakness and definitely he hates it.”

According to him, for that reason, he is trying to create low expectations among his electorate.

“The situation in the country is getting worse and some unpopular reforms are [coming]. He wants to win securely, he wants people to be positive, but he doesn’t want them to expect much from him,” said Gallyamov.

In his campaign, Putin focused more on relations with the West, military strength and perceived victories abroad, especially Crimea.

He held his last campaign event on Wednesday in Sevastopol, Crimea’s biggest city, where he attended celebrations of the fourth anniversary of the Russian annexation of the peninsula and inspected the bridge being built as a link to mainland Russia.

Apart from his Crimea visit, Putin’s only other major campaign event was held in stadium “Luzhniki” which will host the first and the final games during the upcoming football World Cup.

“His campaign is vaguely present in the public sphere […] Putin doesn’t like campaining,” said Gallyamov. “He’s like ‘I don’t need to campaign, I’m working. I don’t need to advertise myself, just check the results of my work’.”

Just like previous elections, Putin has decided not to show up for political debates on state TV which ran between February 27 and March 15.

Broadcast early morning or late at night and dominated by bickering and exchanges of accusations, these debates have attracted attention only for the controversies that they have created, says Stepan Goncharov, a sociologist at Moscow-based independent research centre, Levada.

In one episode, the candidate of Citizens’ Initiative Ksenia Sobchak – the daughter of Putin’s former boss and St Petersburg mayor Anatoly Sobchak – threw water at nationalist candidate Vladimir Zhirinovsky who called her “stupid” and a “prostitute”.

“[These controversies] negate any political value messages. It becomes a circus and people don’t perceive it as a serious political debate,” said Goncharov.

Turnout anxiety

After Navalny was barred from the polls, he called on his supporters to boycott the elections and launched a campaign to register and train election observers, claiming that there might be electoral irregularities.

His team regularly posts on social media about incidents of what they call “illegal campaigning”, including university faculty and administration pressuring students to go and vote.

Local media reported that local administrations across the country are organising various celebrations and events to draw voters to the polling stations.

According to news web portal RBC, regional administrations have been instructed to create a “festive mood” for the elections to encourage higher turnout.

On Sunday, Yevgeny Roizman, the mayor of Russia’s third largest city, Yekaterinburg, said in a video posted on his Youtube channel that there has been an effort to push up turnout levels for the elections.

“I’ve never seen anything like that. Everything has been mobilised: schools, kindergartens, hospitals – it is an unprecedented fight for [a higher] turnout,” said Roizman, who won the mayorship in 2013 running as an independent.

In the video, he also said that there is a minimum of 60 percent turnout that leaders of Russian regional authorities have to achieve in order to “survive”; those who get above 60 percent are able to advance in their careers.

On Monday, Dmitry Peskov, the press secretary of the presidency, commented on the issue saying: “Appeals [to vote] and campaigns by the CEC to promote the elections and voting are completely legitimate and observe existing laws.”

According to Gallyamov, this mobilisation ahead of the elections means that there is a competition among local authorities in Russia’s regions to show loyalty to the Kremlin, especially after a number of governors resigned or were fired in the fall [September-October]. Seeking a high turnout is a Soviet tradition, he says.

“The only way to show that you are loyal was for you to arrange high turnout,” he says. “[These elections] resemble the old Soviet situation.”

The latest poll by state-owned pollster VCIOM projects a turnout of 71 percent. In a December survey by Levada Center, which is barred from reporting during the official campaign period and which was forced to register as a foreign agent for receiving funding from abroad, 58 percent of the respondents said that they would not vote in the elections.

According to journalist and political analyst Konstantin Eggert, the turnout will not be as high as VCIOM’s projection, but also mass irregularities are unlikely.

“I don’t think that falsifications will be massive because Putin indicated that he wants more or less an honest campaign, or at least one that will look honest,” he told Al Jazeera.

In his opinion, whether the boycott would be effective will not be clear, as data will not necessarily register what difference it made and might not be made public. But it could send an important message to the authorities.

“The addressee of the boycott sits in the Kremlin … He will probably know how many people [came out to vote] and he will have to make his own conclusions,” said Eggert.

Follow Mariya Petkova on Twitter: @mkpetkova.