Italy’s south, with weaker infrastructure, fears virus outbreak

Coronavirus has mostly impacted Italy’s northern regions, but many anticipate more cases in the south.

Sicily, Italy – The usually bustling entrance hall of the Department of Agriculture Food and Environment at the University of Catania, Sicily, is deserted.

“All academic activities are temporarily suspended”, says a sign hanging on the main gate.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMexico’s teachers seek relief from pandemic-era spike in school robberies

‘A bad chapter’: Tracing the origins of Ecuador’s rise in gang violence

Why is the US economy so resilient?

Since three professors tested positive for coronavirus after returning from a university conference in northern Italy on March 2, the department became one of the first in the country to cancel classes.

The professors went into self-isolation and none experienced any more serious symptoms.

Weeks later, the entire country is now in a state of lockdown.

Now declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization, COVID-19 has so far killed 631 people and affected more than 10,000 in Italy – the hardest-hit country outside China.

The virus is much more widespread in the north, but the island of Sicily, in the south, has 83 confirmed cases, and Catania – the second-largest city after Palermo, is the most affected city with 41 positive cases.

The distance from the epicentres of the outbreak, the so-called “red zones” in the north’s Lombardy and Veneto regions, meant locals in the south have been taking a “light-minded approach because of the island’s apparent geographical safety”, according to Martina Di Leo, 22, a communications student at the University of Catania.

“I think many young people have not taken this seriously enough yet. Some claimed [life] is too short to spend it in quarantine, and began believing in conspiracy theories about the government’s propaganda to create panic.”

Italy initially locked down northern areas. When the draft of this plan was leaked, hundreds of young people rushed to train stations in the middle of the night, heading south to avoid being “trapped” before the plan was enforced.

“That sudden night exodus could now represent a threat to the south’s health infrastructure, which is not as advanced as the one you may find in the north,” Antonio Fusco, a junior emergency-room doctor at Catania’s Polyclinic, one of only two hospitals in the region in charge of COVID-19 swab tests, told Al Jazeera.

Fusco said it was simply a matter of time before the virus spread south.

In Sicily, where the first coronavirus-related death was reported on March 11, about 19,000 people – mostly students and workers in the north with family roots in the south – have registered their return on an online platform to track people’s movements in and out of the region.

“The south had about two weeks’ advantage to get ready to face the crisis,” Fusco said. “The real challenge begins now.”

With fewer intensive-care beds and medical staff in the region, there are fears that the coronavirus emergency could drag the south’s health system to the edge of collapse.

Fusco and a group of fellow colleagues have launched an online funding campaign to try and bridge some of the financial difficulties expected.

“We are a community; we all need to cooperate,” Fusco said. “Despite the north-south gap, we have some [talented figures] here in the medical field that didn’t emigrate and will become crucial heroes during the peak of the contagion, which I expect to impact us in the next week or two.”

So far, the campaign has raised tens of thousands of euros and inspired similar fundraisers at six other general hospitals in the city.

But Di Leo, who has previously volunteered in the hospital’s pediatrics department, said that while helping one another in a crisis is admirable, it is important to follow the government’s guidelines and keep a physical distance where possible and not crowd emergency rooms.

“After seeing people’s lack of responsibility in the past days, I’m worried about a possible human crisis scenario here.”

As part of the national lockdown, people in Italy can only travel throughout the country if their journeys are essential, justified with certificates that prove medical or work reasons.

“I can stand not going out to party for a few weeks, but being physically unable to visit my grandma has revealed to be the hardest part. I worry about her and her health. I haven’t seen her since early March as a precaution, since she’s in her 80s. I miss her so much,” said Leo.

Elderly people and those with pre-existing conditions are most vulnerable to the virus.

In the view of the anticipated overcrowding, and with fewer than 500 intensive-care beds across the island, triage tents have been placed outside hospitals in Sicily.

“We have to be prepared for all scenarios, including those we don’t wish for, such as choosing who’s more likely to survive”, Fusco said.

In Sicily, an island with more than one million people aged over 65, most of the elderly are living in quarantine in complete isolation, away from relatives and with poor access to services.

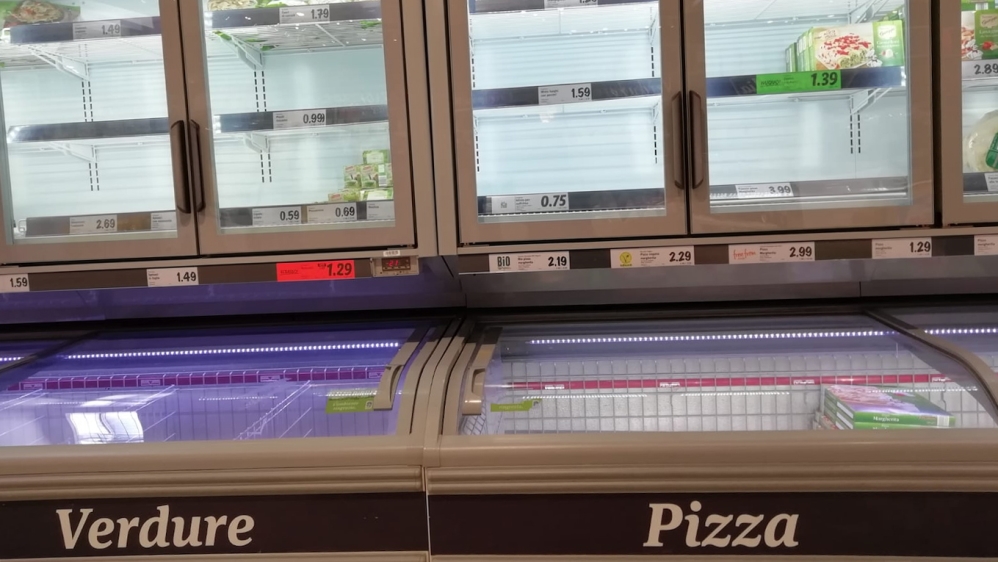

This inspired Francesca Ricotta, a doctor and a city councilor in Catania, to launch an initiative providing free shopping deliveries to the most vulnerable sections of society.

“I thought it was necessary to cater to the most impacted and paradoxically, most forgotten category in these hard times, even with simple acts of care and kindness,” she told Al Jazeera.

About a dozen supermarkets in the city of Catania have signed up.

“This is a test to our sense of humanity, and I hope more solidarity initiatives will keep spreading across the country,” Ricotta says.