Death on the 10th floor: The search for truth in South Africa

Families of anti-apartheid activists who died in the infamous John Vorster Square detention centre pursue justice.

John Vorster Square in central Johannesburg is a building as cold and formidable as the man it was named after: South Africa’s prime minister from 1966 to 1978.

Created as a detention centre for mainly political prisoners, the forbidding grey-and-blue, 10-storey cement building, now known as the Johannesburg Central Police Station, was described in 1971 as the “last word in security” by the liberal South African newspaper, the Rand Daily Mail.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhat happens when activists are branded ‘terrorists’ in the Philippines?

Are settler politics running unchecked in Israel?

Post-1948 order ‘at risk of decimation’ amid war in Gaza, Ukraine: Amnesty

In his book, Timol: A Quest for Justice, Imtiaz Cajee, nephew of anti-apartheid activist Ahmed Timol, wrote of the “paranoia of its turnstiles clamping together like metal teeth”.

To Cajee, whose uncle died at John Vorster Square, it was “the ultimate symbol of the bureaucratisation of fear and horror under apartheid”.

Former Minister of Health and of Public Enterprises Barbara Hogan, who – as the first South African woman to be found guilty of high treason – was detained there, described it as an “iconic institution” that symbolised “the reign of the mad forces”.

The ninth and 10th floors of the building were where the headquarters of the Security Branch was located. They could be accessed by two special lifts that ran straight from the basement to the headquarters.

The Security Branch offices contained special soundproof rooms. Direct-line telephones were connected to the Security Branch headquarters in the capital, Pretoria. The detainee cells were on the lower floors.

Detention without trial

John Vorster Square was one of the architectural symbols of apartheid. But the real pillars of apartheid were the draconian security legislation passed to segregate and intimidate.

One of the most chilling laws passed during Vorster’s leadership was the Terrorism Act of 1967 which allowed the police to detain indefinitely and in solitary confinement anyone suspected of “terrorism” – defined as anyone who might “endanger the maintenance of law and order” – or having information about terrorism. No court could intervene, and no one had access to the detainees.

According to George Bizos, a celebrated human rights lawyer who represented many families of apartheid-era detainees, John Vorster’s name became associated with detention without trial. “The name John Vorster inspired fears among detainees,” said Bizos.

One of the most common methods of torture used in John Vorster Square was “standing torture”, during which detainees were prevented from sleeping or sitting down for many hours on end.

At least 73 political activists are thought to have died in South African police detention between 1963 and 1990 – eight of them during or as a result of their detention at John Vorster Square.

In spite of the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) between 1996 and 1999, most of these cases remained shrouded in secrecy.

That was until inquests into the deaths began to be reopened in 2017, in large part thanks to the tireless efforts of Imtiaz Cajee.

“Imtiaz has been waging a long campaign for truth and justice,” said Howard Varney, lawyer for the Timol family.

The first inquest to be reopened was that of Ahmed Timol, the first activist who died at John Vorster Square.

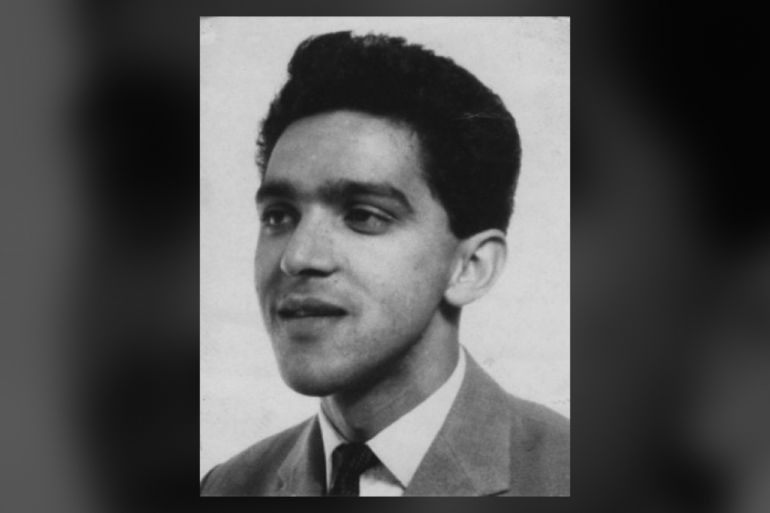

Ahmed Timol

Born in 1941, Ahmed Timol, who was of Indian heritage, was a teacher at Roodepoort Indian High School and a political activist. He was also an underground member of the then-banned South African Communist Party (SACP) and Umkhonto weSizwe, the military wing of the African National Congress (ANC).

Soft-spoken and engaging, Timol interrupted his teaching career in 1967 to travel abroad.

He spent two years in London with fellow South African exiles, before going to the Soviet Union in 1969 to undergo training in Marxist-Leninist ideology at the International Lenin School. He followed that with four weeks of training in London before returning to South Africa in 1970.

According to Timol’s friend and fellow activist, retired academic Salim Essop, Timol’s visit to the Soviet Union was “the highlight of his life”. Essop remembers his friend as being “highly committed to the liberation cause and disciplined”.

Upon returning to South Africa, he set up underground cells of the SACP and, together with Essop, distributed leaflets about the ANC’s activities.

On the night of October 22, 1971, Timol and Essop were arrested at a roadblock in Johannesburg. Banned literature was found in the back of their car.

Both were taken to John Vorster Square. To the 10th floor. A few days later, Timol was dead.

Part of the cover-up

The police claimed that Timol had committed suicide. In 1971, an official inquest into his death concluded the same.

“The inquests held during apartheid were part of the cover-up,” explained Yasmin Sooka, the director of the NGO Foundation for Human Rights and one of the former TRC commissioners. “The magistrates at the time would usually find a suicide.”

Police officers would later joke that “Indians can’t fly”.

On October 30, 1971, the Saturday Star newspaper reported from Timol’s funeral at Roodepoort Muslim cemetery: “Impatient motorists leaned on their hooters as a seemingly endless stream of white-capped Indians held up traffic for more than a dozen blocks at a time in Roodepoort. Schoolgirls pressing handkerchiefs to their faces, T-shirted whites engaging in serious talk with immaculately dressed Muslims – they all formed part of the 1500 mourners following the hearse of Ahmed Timol.”

Plunged to his death

The second detainee to die in John Vorster Square was Wellington Tshazibane, found hanging in his cell on December 11, 1976. He had been arrested four days earlier for alleged complicity in an explosion at the Carlton Centre in Johannesburg.

An official inquest exonerated the police of any wrongdoing.

Elmon Malele, arrested in 1977, was made to stand for six hours while being interrogated at night. He lost his balance, hit his head against the corner of a table and died of a brain haemorrhage. The subsequent inquest found that he had died of natural causes.

On February 15, 1977, detainee Matthews Mabelane plunged to his death from the 10th floor. The police claimed that he had climbed out onto a window ledge in an attempt to escape and had slipped and fallen to his death. An inquest in April 1977 found the cause of death to be “accidental”. He was 23 years old.

Reopened inquests

Ahmed Timol’s inquest was reopened on June 26, 2017. I attended the proceedings in the High Court in Johannesburg.

The atmosphere in the packed court felt heavy with history. The case was about more than Timol’s death. It was about the countless victims of gross human rights violations committed in the name of apartheid.

The two main suspects in the case, Security Branch officers Johannes Gloy and Johannes van Niekerk died before the reopened inquest.

Joao Rodrigues, a former policeman who was with Timol at around the time of his death, was the key witness.

Rodrigues, who was 78 in 2017, claimed repeatedly that he could not remember the events of that day.

At the original inquest, Rodrigues claimed to have seen Timol jump out of a window, but said he could not stop him because he tripped over a chair.

In his new book, The Murder of Ahmed Timol: My Search for Truth, Cajee wrote that a significant amount of evidence relating to his uncle’s case has gone missing, including a page of Rodrigues’ sworn statement.

“A crucial part of his version of what happened when Timol fell from the building has disappeared,” Cajee explained.

The court heard testimony from Essop, who described the use of torture, including electric shock treatments, at John Vorster Square.

A retired academic who now lives in the UK, Essop told Al Jazeera: “The security police engaged in systematic torture. I was tortured in a vault at John Vorster Square by 15 different policemen to the point where I lost consciousness.”

Essop is convinced that Timol was also tortured.

In his judgment, Judge Billy Mothle found that Timol was either pushed from the 10th floor or from the rooftop of the building.

The ruling has been seen as a vindication of the efforts of Timol’s family and friends to have the apartheid security force’s lies about his final days exposed.

The National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) is currently prosecuting Rodrigues for murder and defeating the ends of justice.

Explaining the significance of the reopened inquests, Varney, the lawyer, explained: “The perpetrators had an opportunity to come forward to the TRC and disclose the truth and claim amnesty. They spurned this offer. They must now face justice.”

Neil Aggett

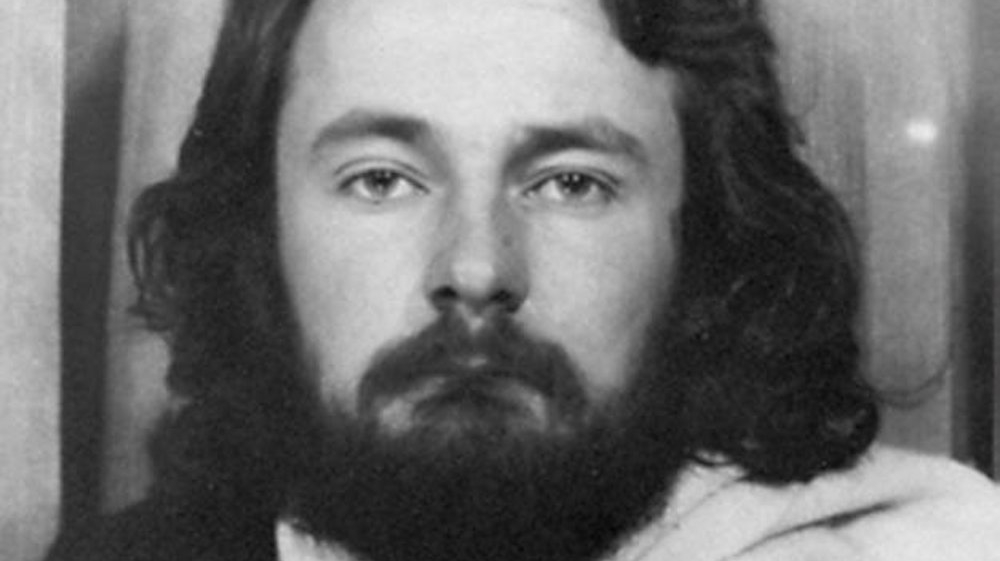

The second case to be reopened was that of Neil Aggett, the first white activist who died in detention during apartheid. The inquest into his case began earlier this year.

Born in Kenya in 1953, Aggett’s family moved to South Africa in 1964. Aggett became a medical doctor and trade union organiser. His internships in Mthatha General Hospital and in Tembisa Hospital, which were located in poor “Black areas” of the Eastern Cape and the old Transvaal province, contributed to his social consciousness. Aggett was convinced that the healing of illness must be accompanied by improving the conditions in which Black South Africans lived.

Jill Burger, Aggett’s sister, told Al Jazeera that his work in these hospitals influenced his political views. “That, as a result of his experiences, he was willing to re-evaluate his principles and values was unique for someone of his background,” she explained.

Aggett was arrested on November 27, 1981, detained under the Terrorism Act, and taken to John Vorster Square, where he was repeatedly interrogated and tortured by Special Branch officers.

Seventy days later, on February 5, 1982, he was found dead in his cell, having allegedly hung himself with a kikoi scarf, a scarf made of African fabric. He was 28.

At the reopened inquest, Aggett’s fellow anti-apartheid activist Keith Coleman described him as “a person of great integrity, little ego and very committed”.

Although a high-profile inquest in 1982 showed how an 80-hour interrogation in the days before his death contributed to it, the security police were cleared of any wrongdoing, and his death was ruled a suicide.

The TRC’s final five-volume report, handed to then-president Nelson Mandela in 1998, found the apartheid state, its minister of police, its commissioner of police and the head of the Security Branch responsible for Aggett’s death.

At the reopened inquest, fellow anti-apartheid activist Jabu Ngwenya, who was imprisoned with Aggett at John Vorster Square, said he believes Aggett’s body was moved to a cell to make it look as if he had hung himself. “He had died on the 10th floor,” said Ngwenya.

The remaining hearings in the Aggett inquest have been postponed until June.

‘Unfinished business’

The Timol and Aggett cases resurrect many of the questions raised during the TRC and can, perhaps, be understood as a way of completing, in the words of former TRC commissioner Dumisa Ntsebeza, the TRC’s “unfinished business”.

One of the features of the TRC that was both praised and criticised was that amnesty could be granted to those who fully disclosed their actions. While the conditional amnesty model was lauded as innovative and reconciliation-building, there were crucial gaps, most notably the fact that those who were refused amnesty were never prosecuted. In the two decades since the work of the TRC was concluded, there have been only a handful of prosecutions.

“Indeed, the failure to prosecute those who did not receive amnesty renders the amnesty process entirely meaningless,” Varney explained. “It may as well have been a de facto blanket amnesty for all.”

Sooka believes that one of the problems with the amnesty scheme was that it was mostly the foot soldiers who applied for amnesty and not the politicians and security force commanders who issued the orders. “Those who created this milieu …, by and large, the politicians, in a sense got away with it,” she said.

Political interference

So, why did it take so long for the NPA to reopen the apartheid-era inquests? Imtiaz Cajee first applied for his uncle’s case to be reopened in 2003.

“They were asking me to do their work,” said Cajee of the NPA. “The cops involved in my uncle’s matter were alive, and they failed to interview them. It was embarrassing that the NPA asked me to get additional information. It was what they were mandated to do.”

As Lukhanyo Calata, son of murdered activist Fort Calata who was one of the “Cradock Four” killed in 1985, stated in an affidavit to the Commission of Inquiry – or Zondo Commission – into state capture: “Had [Timol’s death] been investigated, the main perpetrators would have been held to account, since the last suspect only died in 2012. This amounts to a travesty of justice.”

In their efforts to get the inquests reopened, the Timol and Aggett families said they received no help from the state. They had to conduct investigations themselves and rely on the support offered by pro bono lawyers, such as Howard Varney, who represents both families.

According to Motheba Mohapi, the daughter of slain activist Mapetla Mohapi, the resource implications of this could inhibit families from applying for inquests to be reopened.

Some have argued that not only has there been a lack of political will to prosecute perpetrators of apartheid crimes, but that there has been active political interference, pressuring the NPA not to.

“The TRC made adverse findings against all the main role players, including the ANC,” said Varney. “The ANC did not want these cases pursued to protect its own. In former police chief Jackie Selebi’s words – put to former Director of Public Prosecutions Vusi Pikoli: ‘If you go after the apartheid generals, then you open the door to cases against us,’ and that was not acceptable. So, to the ANC, the solution was to stop all cases.”

Jessie Duarte, the deputy secretary-general of the ANC, told Al Jazeera that she “strongly disagrees” with the suggestion that there was political interference, adding that: “The ANC supports the reopening of the cases.”

Yasmin Sooka believes the onus has been on families to fight for cases to be reopened. “If there is progress in TRC matters, it is usually because of pressure by the victims’ families or civil society. In this sense, all decisions by the NPA are very reactive – there is no proactivity in pursuing the TRC cases.”

How does the NPA decide which cases to prioritise?

“Typically, the priority is given to cases in which families are willing to pursue the matter and evidence is available – a luxury given the amount of time that has lapsed,” said Sooka.

Closure for families

For many families of anti-apartheid activists murdered by the security forces, the past decades have been shrouded in uncertainty. According to Cajee, the reopening of inquests “opened a door for many families. They now live in hope again that the inquests of their loved ones might be reopened.”

The case of Motheba Mohapi’s father, Mapetla Mohapi, has not yet been reopened.

One of the activists supporting the Black Consciousness Movement, Mapetla worked closely with Steve Biko and was also active in the South African Students Organisation. Mapetla was detained without charge on July 16, 1976. Twenty days later, he died in police custody.

The police said he had hanged himself with a pair of jeans.

Motheba Mohapi was two-and-a-half years old when her father died.

In 2017, she and her family tried to visit the cell where he died. “I went there with members of my family,” she said. But they were not granted access.

She was finally granted it in 2019, and described the experience as both “emotional and joyful”.

“There is a special connection when you try to imagine the person in that space,” she explained.

When she heard of the reopened inquests, “the hope and desire opened up that this might be possible for us as well”.

The post-apartheid government conferred The Order of Luthuli on Mapetla for his struggle for a democratic South Africa. But what is most important to Mohapi is a public “acknowledgement of the injustice and the suffering of the family and the correction of history”.

Thembi Nkadimeng, the mayor of Polokwane, wants the inquest into the 1983 disappearance of her sister, anti-apartheid activist Nokuthla Simelane, reopened. “What my family wants is my sister’s remains,” said Nkadimeng.

The death of activist Fort Calata was the subject of two inquests, in 1987 and 1992. The first found that “no one is to blame”. At the 1992 inquest, the judge found the state to be responsible for the killing, but nobody was named, and no prosecution followed.

His son, Lukhanyo Calata, journalist and author of the book, My Father Died For This, said the family is not interested in another inquest. “What we want is for the ANC to create the society that my father gave his life for,” he said.

For now, most families only have the official version of the truth. A poem, In Detention by Chris van Wyk, captures the absurdity of that:

He fell from the ninth floor

He hanged himself

He slipped on a piece of soap while washing

He hanged himself

He slipped on a piece of soap while washing

He fell from the ninth floor

He hanged himself while washing

He slipped from the ninth floor

He hung from the ninth floor

He slipped from the ninth floor while washing

He fell from a piece of soap while slipping

He hung from the ninth floor

He washed from the ninth floor while slipping

He hung from a piece of soap while washing