Data fog: Why some countries’ coronavirus numbers do not add up

Reported numbers of confirmed cases have become fodder for the political gristmill. Here is what non-politicians think.

Have you heard the axiom “In war, truth is the first casualty”?

As healthcare providers around the world wage war against the COVID-19 pandemic, national governments have taken to brawling with researchers, the media and each other over the veracity of the data used to monitor and track the disease’s march across the globe.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMexico’s teachers seek relief from pandemic-era spike in school robberies

‘A bad chapter’: Tracing the origins of Ecuador’s rise in gang violence

Why is the US economy so resilient?

Allegations of deliberate data tampering carry profound public health implications. If a country knowingly misleads the World Health Organization (WHO) about the emergence of an epidemic or conceals the severity of an outbreak within its borders, precious time is lost. Time that could be spent mobilising resources around the globe to contain the spread of the disease. Time to prepare health systems for a coming tsunami of infections. Time to save more lives.

No one country has claimed that their science or data is perfect: French and US authorities confirmed they had their first coronavirus cases weeks earlier than previously thought.

Still, coronavirus – and the data used to benchmark it – has become grist for the political mill. But if we tune out the voices of politicians and pundits, and listen to those of good governance experts, data scientists and epidemiological specialists, what does the most basic but consequential data – the number of confirmed cases per country – tell us about how various governments around the globe are crunching coronavirus numbers and spinning corona-narratives?

What the good governance advocates say

Similar to how meteorologists track storms, data scientists use models to express how epidemics progress, and to predict where the next hurricane of new infections will batter health systems.

This data is fed by researchers into computer modelling programmes that national authorities and the WHO use to advise countries and aid organisations on where to send medical professionals and equipment, and when to take actions such as issuing lockdown orders.

The WHO also harnesses this data to produce a daily report that news organisations use to provide context around policy decisions related to the pandemic. But, unlike a hurricane, which cannot be hidden, epidemic data can be fudged and manipulated.

“The WHO infection numbers are based on reporting from its member states. The WHO cannot verify these numbers,” said Michael Meyer-Resende, Democracy Reporting International’s executive director.

To date, more than 8 million people have been diagnosed as confirmed cases of COVID-19. Of that number, more than 443,000 have died from the virus, according to Johns Hopkins University.

Those numbers are commonly quoted, but what is often not explained is that they both ultimately hinge on two factors: how many people are being tested, and the accuracy of the tests being administered. These numbers we “fetishise”, said Meyer-Resende, “depend on testing, on honesty of governments and on size of the population”.

“Many authoritarian governments are not transparent with their data generally, and one should not expect that they are transparent in this case,” he said. To test Meyer-Resende’s theory that less government transparency equals less transparent COVID-19 case data, Al Jazeera used Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index and the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index as lenses through which to view the number of reported cases of the coronavirus.

The examination revealed striking differences in the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases that those nations deemed transparent and democratic reported compared to the numbers reported by nations perceived to be corrupt and authoritarian.

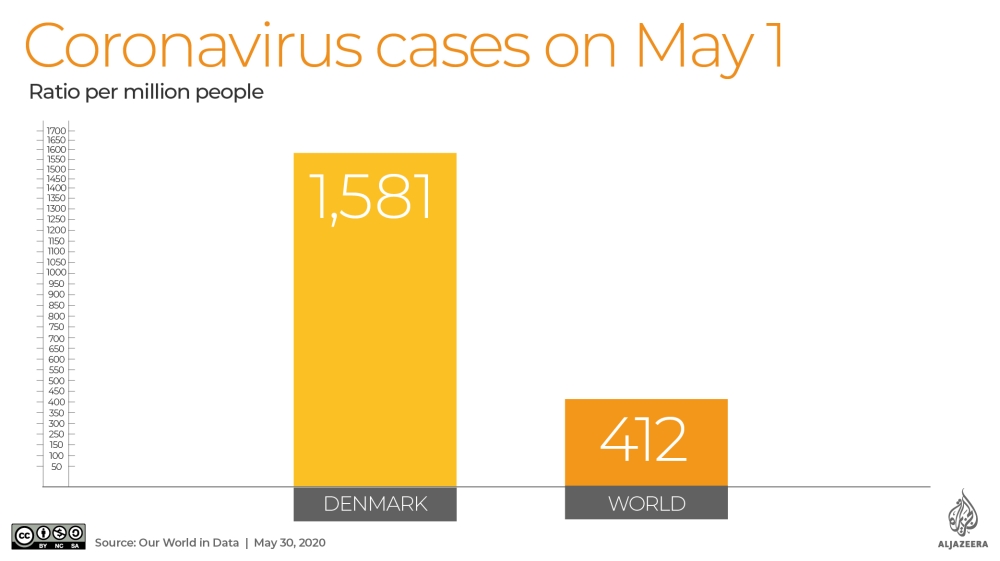

Denmark, with a population of roughly six million, is ranked in the top 10 of the most transparent and democratic countries. The country reported on May 1 that it had 9,158 confirmed cases of COVID-19, a ratio of 1,581 confirmed cases per million. That was more than triple the world average for that day – 412 cases per million people – according to available data.

Meanwhile, Turkmenistan, a regular in the basement of governance and corruption indexes, maintains that not one of its roughly six million citizens has been infected with COVID-19, even though it borders and has extensive trade with Iran, a regional epicentre of the pandemic.

Also on May 1, Myanmar, with a population of more than 56 million, reported just 151 confirmed cases of infection, a rate of 2.8 infections per million. That is despite the fact that every day, roughly 10,000 workers cross the border into China, where the pandemic first began.

On February 4, Myanmar suspended its air links with Chinese cities, including Wuhan, where COVID-19 is said to have originated last December (however, a recent study reported that the virus may have hit the city as early as August 2019).

“That just seems abnormal, out of the ordinary. Right?” said Roberto Kukutschka, Transparency International’s research coordinator, in reference to the numbers of reported cases.

“In these countries where you have high levels of corruption, there are high levels of discretion as well,” he told Al Jazeera. “It’s counter-intuitive that these countries are reporting so few cases, when all countries that are more open about these things are reporting way more. It’s very strange.”

While Myanmar has started taking steps to address the pandemic, critics say a month of preparation was lost to jingoistic denial. Ten days before the first two cases were confirmed, government spokesman Zaw Htay claimed the country was protected by its lifestyle and diet, and because cash is used instead of credit cards to make purchases.

Turkmenistan’s authorities have reportedly removed almost all mentions of the coronavirus from official publications, including a read-out of a March 27 phone call between Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev and Turkmen President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov.

It is unclear if Turkmenistan even has a testing regime.

Russia, on the other hand, touts the number of tests it claims to have performed, but not how many people have been tested – and that is a key distinction because the same person can be tested more than once. Transparency International places Russia in the bottom third of its corruption index.

On May 1, Russia, with a population just above 145 million, reported that it had confirmed 106,498 cases of COVID-19 after conducting an astounding 3.72 million “laboratory tests”. Just 2.9 percent of the tests produced a positive result.

Remember, Denmark’s population is six million, or half that of Moscow’s. Denmark had reportedly tested 206,576 people by May 1 and had 9,158 confirmed coronavirus cases, a rate of 4.4 percent. Finland, another democracy at the top of the transparency index, has a population of 5.5 million and a positive test result rate of 4.7 percent.

This discrepancy spurred the editors of PCR News, a Moscow-based Russian-language molecular diagnostics journal, to take a closer look at the Russian test. They reported that in order to achieve a positive COVID-19 result, the sample tested must contain a much higher volume of the virus, or viral load, as compared to the amount required for a positive influenza test result.

In terms of sensitivity or ability to detect COVID-19, the authors wrote: “Is it high or low? By modern standards – low.”

They later added, “The test will not reveal the onset of the disease, or it will be decided too early that the recovering patient no longer releases viruses and cannot infect anyone. And he walks along the street, and he is contagious.”

Ostensibly, if that person then dies, COVID-19 will not be certified as the cause of death.

Good governance experts see a dynamic at play.

Countries who test less will be shown as less of a problem. Countries that test badly will seem as if they don't have a problem. Numbers are very powerful.

“In many of these countries, the legitimacy of the state depends on not going into crisis,” said Kukutschka, adding that he counts countries with world-class health systems among them.

“Countries who test less will be shown as less of a problem. Countries that test badly will seem as if they don’t have a problem,” said Meyer-Resende. “Numbers are very powerful. They seem objective.”

Meyer-Resende highlighted the case of China. “The Chinese government said for a while that it had zero new cases. That’s a very powerful statement. It says it all with a single digit: ‘We have solved the problem’. Except, it hadn’t. It had changed the way of counting cases.”

China – where the pandemic originated – recently escaped a joint US-Australian-led effort at the World Health Assembly to investigate whether Beijing had for weeks concealed a deadly epidemic from the WHO.

China alerted the WHO about the epidemic on December 31, 2019. Researchers at the University of Hong Kong estimated that the actual number of COVID-19 cases in China, where the coronavirus first appeared, could have been four times greater in the beginning of this year than what Chinese authorities had been reporting to the WHO.

“We estimated that by Feb 20, 2020, there would have been 232,000 confirmed cases in China as opposed to the 55,508 confirmed cases reported,” said the researchers’ report published by the Lancet.

The University of Hong Kong researchers attribute the discrepancy to ever-changing case definitions, the official guidance that tells doctors which symptoms – and therefore patients – can be diagnosed and recorded as COVID-19. China’s National Health Commission issued no less than seven versions of these guidelines between January 15 and March 3.

All of which adds to the confusion.

“Essentially, we are moving in a thick fog, and the numbers we have are no more than a small flashlight,” said Meyer-Resende.

What the epidemiological expert thinks

Dr Ghassan Aziz monitors epidemics in the Middle East. He is the Health Surveillance Program manager at the Doctors Without Borders (MSF) Middle East Unit. He spoke to Al Jazeera in his own capacity and not on behalf of the NGO.

“I think Iran, they’re not reporting everything,” he told Al Jazeera. “It’s fair to assume that [some countries] are underreporting because they are under-diagnosing. They report what they detect.”

He later added that US sanctions against Iran, which human rights groups say have drastically constrained Tehran’s ability to finance imports of medicines and medical equipment, could also be a factor.

“Maybe [it’s] on purpose, and maybe because of the sanctions and the lack of testing capacities,” said Aziz.

Once China shared the novel coronavirus genome on January 24, many governments began in earnest to test their populations. Others have placed limits on who can be tested.

In Brazil, due to a sustained lack of available tests, patients using the public health network in April were tested only if they were hospitalised with severe symptoms. On April 1, Brazil reported that 201 people had died from the virus. That number was challenged by doctors and relatives of the dead. A month later, after one minister of health was fired and another resigned after a week on the job, the testing protocols had not changed.

On May 1, Brazil reported that COVID-19 was the cause of death for 5,901 people. On June 5, Brazil’s health ministry took down the website that reported cumulative coronavirus numbers – only to be ordered by the country’s Supreme Court to reinstate the information.

Right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro has repeatedly played down the severity of the coronavirus pandemic, calling it “a little flu”. Brazilian Supreme Court Justice Gilmar Mendes accused the government of attempting to manipulate statistics, calling it “a manoeuvre of totalitarian regimes”.

A manipulação de estatísticas é manobra de regimes totalitários. Tenta-se ocultar os números da #COVID19 para reduzir o controle social das políticas de saúde. O truque não vai isentar a responsabilidade pelo eventual genocídio. #CensuraNao #DitaduraNuncaMais

— Gilmar Mendes (@gilmarmendes) June 6, 2020

Brazil currently has the dubious distinction of having the second-highest number of COVID-19 deaths in the world, behind the US. By June 15, the COVID-19 death toll in the country had surpassed 43,300 people.

Dr Aziz contends that even with testing, many countries customarily employ a “denial policy”. He said in his native country, Iraq, health authorities routinely obfuscate health emergencies by changing the names of outbreaks such as cholera to “endemic diarrhoea”, or Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever to “epidemic fever”.

“In Iraq, they give this idea to the people that ‘We did our best. We controlled it,'” Dr Aziz said. “When someone dies, ‘Oh. It’s not COVID-19. He was sick. He was old. This is God’s will. It was Allah.’ This is what I find so annoying.”

What the data scientist says

Sarah Callaghan, a data scientist and the editor-in-chief of Patterns, a data-science journal, told Al Jazeera the numbers of confirmed cases countries report reflect “the unique testing and environmental challenges that each country is facing”.

But, she cautioned: “Some countries have the resources and infrastructure to carry out widespread testing, others simply don’t. Some countries might have the money and the ability to test, but other local issues come into play, like politics.”

According to Callaghan, even in the best of times under the best circumstances, collecting data on an infectious disease is both difficult and expensive. But despite the difficulties presented by some countries’ data, she remains confident that the data and modelling that is available will indeed contribute much to understanding how COVID-19 spreads, how the virus reacts to different environmental conditions, and discovering the questions that need answers.

Her advice is: “When looking at the numbers, think about them. Ask yourself if you trust the source. Ask yourself if the source is trying to push a political or economic agenda.”

“There’s a lot about this situation that we don’t know, and a lot more misinformation that’s being spread, accidentally or deliberately.”