Anatomy of a disinformation campaign: The coup that never was

How did a few Saudi influencers and thousands of sock puppets trick media into reporting on a made-up coup in Qatar?

In the early hours of May 4, news of a coup in Qatar started trending on Twitter.

At about 1:30am Saudi time, a mysterious account that uses a photo of Saudi Arabia’s King Salman as its profile picture tweeted that an explosion was heard in the Qatari city of al-Wakra, just outside the capital, Doha. Soon after, a Saudi-based account with only a few followers replied to the tweet, claiming there had been a coup attempt against Qatar’s emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsThe Qatar blockade

Lebanon is experiencing a social revolution

By all accounts, residents of al-Wakra had heard a bang that night. This, in and of itself, was not unusual – people living in this city are used to being startled by the sonic boom of jets from time to time. Nevertheless, the fact that a loud bang was heard near the capital gave people motivated to spread disinformation about Qatar a peg on which to hang the plausibility of their claims.

10/ The trend seems to have began around 1 am UTC. This account, @faisalva_ , who has a profile pic of King Salman, posted a video reporting gunshots and explosions. Another account, self described as a Saudi radiologist, said a coup was happening pic.twitter.com/uI8S96bfvD

— Marc Owen Jones (@marcowenjones) May 4, 2020

Soon after the first tweet claiming that there had been a coup in Doha, the Arabic hashtag “al-Wakra” began trending on Twitter in Qatar, and “coup in Qatar” began trending in Saudi Arabia. In a matter of hours, hundreds of thousands of tweets about the alleged coup attempt were produced across several hashtags, making “coup in Qatar” the number-one trending topic in both Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

The narrative that was being pushed on Twitter was that former Qatari Prime Minister Hamad bin Jassim, disgruntled by a corruption investigation, had sought to overthrow the emir, with Turkish troops stationed in the country interceding on behalf of the current leadership.

The vast majority of accounts tweeting about this alleged coup attempt appeared to be based in Saudi Arabia, raising suspicions that the rumours could be part of a long-running Saudi-led campaign to discredit the Qatari leadership.

On June 5, 2017, four Arab countries – Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt and Bahrain – severed diplomatic ties with Qatar, accusing it of funding “terrorism” and fomenting regional instability – allegations Doha rejects. The countries also cut off all land, air and sea links to Qatar.

The move was followed by a relentless disinformation campaign, led mostly through social media, aiming to create the impression that the Qatari leadership is in crisis and that Riyadh’s aggressive policies towards its Gulf neighbour are justified.

A few days after the blockade was imposed, for example, there were claims made over Twitter of a coup being under way in Qatar. At the time, these unfounded claims were swiftly reported on, and supported by, media outlets that have links to the blockading countries.

This month’s Twitter-storm about the alleged coup attempt in Qatar appeared to have several similarities with the Saudi-led disinformation efforts of 2017.

Suspicious, I decided to investigate.

‘Sock puppets’ and influencers

Most of the accounts spreading the rumours appeared to be anonymous and based in Saudi Arabia.

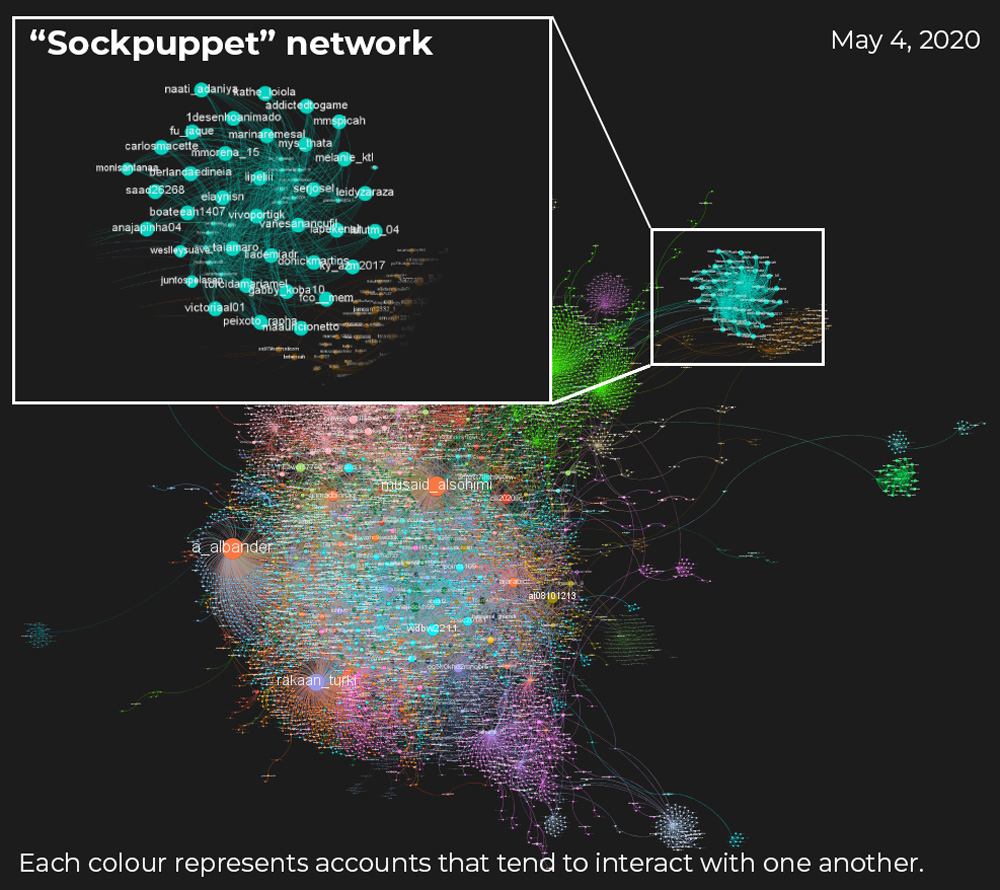

Hundreds of others, with European-sounding names, meanwhile, were “sock puppets” – accounts set up under fake names to bolster a particular point of view online. Indeed, none of these accounts had a history of tweeting in Arabic or on Middle Eastern politics prior to May 4.

However, amid all these anonymous and clearly fake accounts, I found a key group of verified accounts spreading disinformation. Abdallah al-Bandar, a Saudi presenter for the international news channel Sky News Arabia who has 234,000 followers on Twitter, for example, added fuel to the rumours by tweeting early on May 4 that warplanes were flying over Qatar.

Numerous other influential Saudis contributed to the rapid spread of the rumours by sharing false, unverified information on social media, including influencer Monther Al Shaykh Mubarak, sports commentator Musaid AlSohimi, and poet Abdlatif Al Shaykh.

9/ As we can see, most of the most influential 'facilitators' of the rumours are verified Saudi accounts such as @Musaid_AlSohimi – @a_albander @Ahmadbinnaqi Interestingly, Musad AlSohimi has #NUFC in his bio, presumably routing for the #NUFCtakeover pic.twitter.com/aBgS4po014

— Marc Owen Jones (@marcowenjones) May 4, 2020

Doctored videos

Amid the tweets purporting a coup attempt to be under way in Qatar, “evidence” in the form of short videos allegedly showing gunfire and explosions near Doha were also circulated.

It did not take long to establish that these videos were either heavily doctored or completely fake. One video, which had been shared thousands of times as proof of the alleged clashes in al-Wakra, was actually recorded in Riyadh, in April 2018. Another video that was widely shared in the same context turned out to be from a chemical explosion that took place in 2015, in Tianjin, China.

Several Saudi-based Twitter accounts and sock puppets also shared a video clip shot in al-Wakra on the morning of May 4, multiple gunshots could be heard in the video’s soundtrack. However, it was soon revealed that the video had originally been created by a Qatari citizen named Rashed al-Hamli to mock the claims that there was a coup in the country. Al-Hamli’s light-hearted video making fun of the coup claims was apparently doctored to remove his voice and replace it with the sound of gunfire.

The efforts to convince the world that the Qatari state is unstable were not limited to the doctoring of videos. The originators of the apparent disinformation campaign also created a fake tweet by former Prime Minister Hamad bin Jassim to try and prove that a violent coup attempt had taken place in the country.

A second spike

By the morning of May 5, the hashtag “coup in Qatar” had 150,000 tweets. After a brief respite, likely caused by the rapid debunking of the claims by Qatari authorities and residents, the story picked up again on May 12-13.

The same rumours were once again being propagated by the same Saudi influencers, Saudi-based anonymous accounts and sock puppets, suggesting some form of coordination.

During this second spike, the disinformation campaign was more sophisticated than before. The verified accounts belonging to an American musician and a baseball player were hacked, repurposed as Arabic accounts, and used to boost the salience of the disinformation.

This time around, the fake videos used to substantiate the claims were also more sophisticated. A short clip that showed two boys filming an explosion near Katara in Doha, for example, was circulated widely. The video was more believable than the ones shared before, as it was definitely filmed in Qatar. A quick open-source intelligence (OSINT) investigation, however, showed that the video was most likely filmed during a fireworks festival in February.

Feeding Twitter disinformation to the media

It is clear that the rumours about an alleged coup attempt in Qatar did not organically materialise on social media, but were the product of a coordinated campaign similar to the one that disseminated disinformation about the country back in 2017.

The story has now died down – many of the Twitter accounts that contributed to the disinformation campaign have either been suspended by Twitter or changed their screen names.

This, however, does not mean this complex disinformation campaign was unsuccessful.

Media outlets around the world already reported on the rumours promoted by these accounts, creating the impression that the Qatari state is weak and unstable.

While media organisations with known political and economic links to Riyadh, such as Al Arabiya or Independent Arabia, published opinion pieces and news reports supporting the claims, other news sources contributed to the disinformation campaign simply by reporting on the claims made on social media without questioning their credibility.

Disinformation campaigns often seek not to prove the claims they make, but to provoke discord, instability, and uncertainty in their targets. Simply by reporting that there were “rumours of a coup in Qatar”, therefore, many independent media outlets played into the hands of the propagandists behind this campaign.

The real story is not that there were rumours of a coup, but that there was a disinformation campaign designed to give the illusion of a coup. In an age where disinformation is rife, even a technically factual report on social media trends can fan the flame of fake news.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.