Venezuela’s worst economic crisis: What went wrong?

Country sitting on world’s biggest oil reserves is now region’s poorest performer in terms of GDP growth per capita.

Venezuela is experiencing the worst economic crisis in its history, with an inflation rate of over 400 percent and a volatile exchange rate.

Heavily in debt and with inflation soaring, its people continue to take to the streets in protest.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsBehind India’s Manipur conflict: A tale of drugs, armed groups and politics

China’s economy beats expectations, growing 5.3 percent in first quarter

Inside the pressures facing Quebec’s billion-dollar maple syrup industry

President Nicolas Maduro announced the highest increase in the minimum wage ordered by him – 65 percent of the monthly income, and recently announced the creation of a new popular assembly with the ability to re-write the constitution.

International concern raised, with Chile and Argentina among the countries expressing worry. The Venezuelan opposition says the move further weakens the chances of holding a vote to remove Maduro.

But backing has come from regional leftist allies including Cuba. Bolivia’s President Evo Morales said Venezuela had the right to “decide its future… without external intervention.”

The country sits on the world’s largest oil reserves, but, over the past decade, it has been the region’s poorest performer in terms of growth of GDP per capita.

Since 2014 the government has not made any economic data available making it difficult to track.

But what went wrong?

1) What is the state of Venezuela’s economy today?

Venezuela depends heavily on its oil. It has the largest oil reserves in the world which, in 2014, had 298 billion barrels of proved oil reserves.

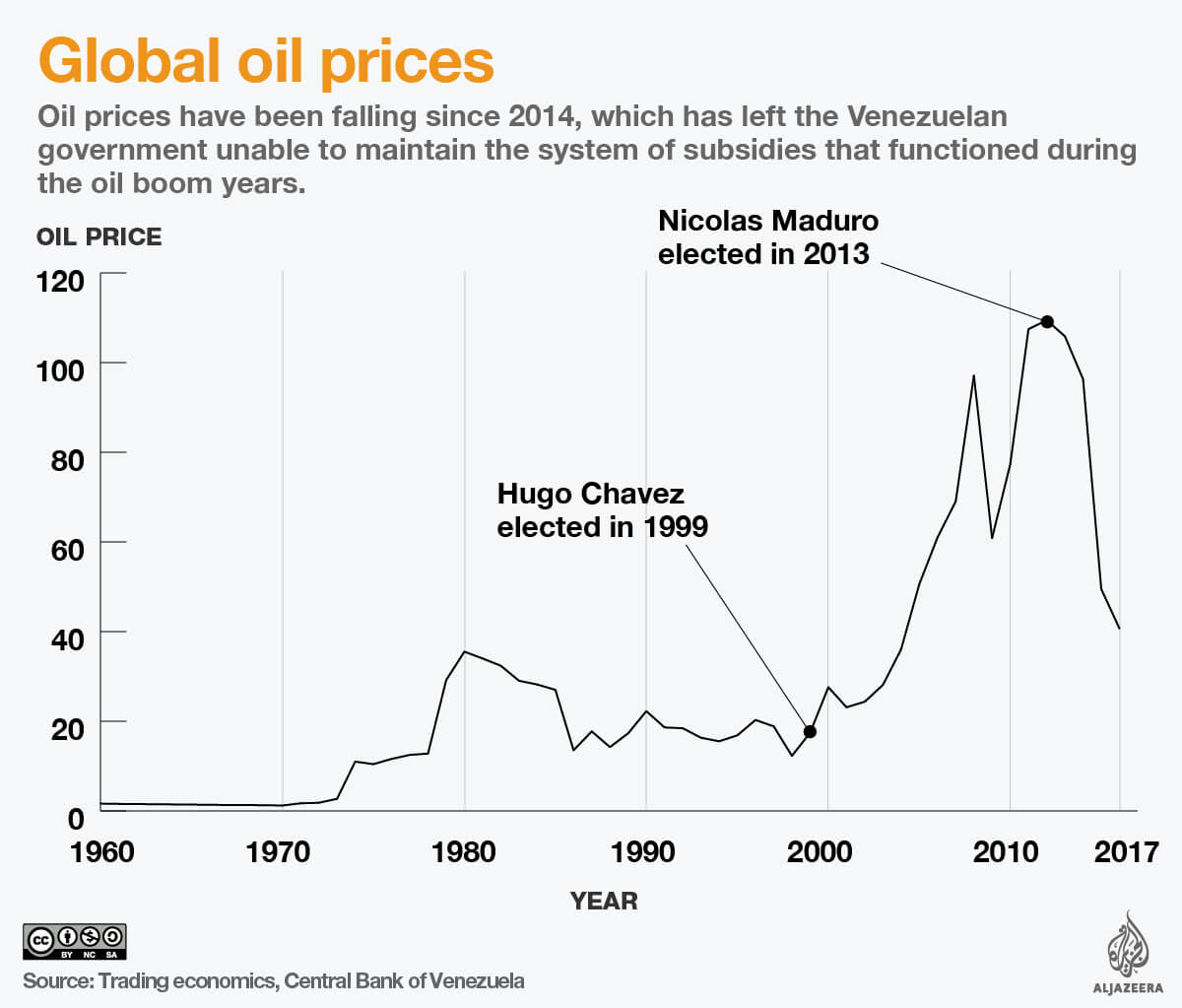

Oil revenue has sustained Venezuela’s economy for years. During the presidency of Hugo Chavez, the price of oil reached a historic high of $100 a barrel.

The billions of dollars in revenue were used to finance social programmes and food subsidies.

But when the price of oil fell, those programmes and subsidies became unsustainable.

READ MORE- Venezuela: What is happening?

The government is also running out of cash. According to the Central Bank of Venezuela, the country has $10.4bn in foreign reserves left, and it is estimated to have a debt of $7.2bn.

According to International Monetary Fund (IMF) figures, in 2016, the country had a negative growth rate of minus 8 percent, an inflation rate of 481 percent and an unemployment rate of 17 percent that is expected to climb to 20 percent this year.

Currency controls have limited imports, putting a strain on supply.

The government controls the price of basic goods, this has led to a black market that has a strong influence on prices too.

The most recent report by CENDAS (Centre for Documentation and Social Analysis) indicates that in March 2017 a family of five needed to collect 1.06 million bolivars to pay for the basic basket of goods for one month, that includes food and hygiene items, as well as spending on housing, education, health and basic services.

The cost of that basket rosed by 15.8 percent that is an increase of 424 percent compared to 2016.

2) Shortages of food and medicines

During the rule of Hugo Chavez, the price of key items, food and medicines were reduced. Products became more affordable but they were below the cost of production.

Private companies were expropriated, and to stop people from changing the national currency into dollars, Chavez restricted the access to dollars and fixed the rate.

When it became unprofitable for Venezuelan companies to continue producing their own products, the government decided to import them from abroad, using oil money.

But oil prices have been falling since 2014, which has left the economic system unable to maintain the system of subsidies and price controls that functioned during the oil boom years.

We are facing a food crisis

The inability to pay for imports with bolivares coupled with the decline in oil revenues has led to a shortage of goods.

The state has tried to ration food and set their prices, but the consequence is that products have disappeared from shops and ended up in the black market, overpriced.

As many as 85 of every 100 medicines are missing in the country. Shortages are so extreme that patients sometimes take medicines ill-suited for their conditions, doctors warn.

Given the long litany of woes, some analysts think there are two options before Maduro’s government: to default on its debt or to stop importing food.

“For those of us who work with a normal wage, we can barely eat, it’s like a war situation [we eat what we can get and what we can find] because the price of food is astronomical,” Leonardo Bruzal, a Venezuelan citizen, told Al Jazeera.

Many Venezuelans search for food, occasionally opting to eat wild fruit or rubbish. “We are facing a food crisis,” analyst Jose Guerra explained to Al Jazeera.

3) Hyperinflation

Venezuela has established different exchange rate systems for its national currency, the bolivar.

One rate was established for what the government determines to be “essential goods”, other for “non-essential goods” and another one for people.

The two primary rates overvalue the bolivar, but the black market values the bolivar at near worthless.

This has generated a situation in which Venezuelans are opting for dollars instead of bolivares.

- The government maintains a trade around 710 bolivares per US dollar.

- At 10 under Venezuela’s other official rate

- But the black-market rate has risen to 4,283 bolivars for one dollar.

The government has also increased the number of bolivares available in the streets, as the money in circulation has not been enough to pay for basic goods that today cost a lot more. This has stoked fears of hyperinflation.

On April 30, Maduro announced a 34.42 percent increase in the total salary.

Faced with this new wage increase – the 15 during Maduro’s mandate – economists reacted saying that this measure is insufficient to deal with inflation, which they warn is going to worsen with this setting.

4) Venezuela before Chavez

Between 1900 and 1920, Venezuela’s per capita GDP had grown at a rate of barely 1.8 percent. Between 1940 and 1948 it grew at 6.8 percent per annum.

By the 1960s and the 1970s, the governments in Venezuela were able to maintain social harmony by spending fairly large amounts on public programmes.

In 1970, Venezuela had become the richest country in Latin America, and one of the 20 richest countries in the world, with a per capita higher that Spain, Greece and Israel, Ricardo Hausmann explains in his book Venezuela Before Chavez: Anatomy of an Economy Collapse.

Venezuelan workers were known for enjoying the highest wages in Latin America, a situation that dramatically changed when oil prices collapsed during the 1980s.

The economy contracted and inflation levels rose, remaining between 6 and 12 percent from 1982 to 1986.

The inflation rate surged in 1989 to 81 percent, the same year the capital city of Caracas experienced rioting during the Caracazo following the cuts in government spending and the opening of markets by the then president, Carlos Andres Perez.

Venezuela’s GDP went from -8.3 percent in 1989 to 4.4 percent in 1990, and 9.2 percent in 1991. However, wages remained low and unemployment high among Venezuelans.

By the mid-1990s under Caldera, Venezuela saw annual inflation rates of 50-60 percent, and an inflation rate of 100 percent in 1996, three years before Chavez took office.

The number of people living in poverty rose from 36 percent to 66 percent in 1995 with the country suffering a severe bank crisis.

When Chavez first took office as president in 1999, the country was not an economic model: almost half the population was below the country’s poverty line.

However, the country was an affluent country and the government finances were in tolerably good shape.