Finding Kukan and a piece of Chinese-American history

How the search for a strong Chinese-American female pop-culture icon led to the rediscovery of a lost historic film.

It was an old box, tucked away and forgotten in an office cabinet, that caught Michelle Scott’s eye.

She pulled it from its niche and eased it open, revealing a mess of slides, photographic negatives and portrait prints.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsInside the pressures facing Quebec’s billion-dollar maple syrup industry

‘Accepted in both [worlds]’: Indonesia’s Chinese Muslims prepare for Eid

Photos: Mexico, US, Canada mesmerised by rare total solar eclipse

They were a photography student’s dream, and Scott dived right in.

“Most of them were film, black-and-white darkroom, eight by 10, just gorgeous,” she said, still enthusiastic.

Scott took her unearthed treasures up to the kitchen to search for some answers.

The box was clearly the property of her grandfather, Reynolds “Rey” Scott, a man she only known when she was a young child. But some of the photos suggested a different person to the one she recalled.

“What I remember of him was that he was very old,” she said with a laugh. “He looked like Santa Claus a little bit, with the all-white hair and the white beard, and he had a cane. He pretty much kept to himself.”

Michelle’s father joined her in the kitchen. She showed him the contents of the box and started to ask questions, the answers to which had implications far beyond their home in the American town of Cumming, Georgia.

Losing Kukan

![[Courtesy Robin Lung]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/8915070ac0f943d3b117ff33417fd9f1_6.jpeg)

Kukan was missing, and Kukan would probably never be found. That was the bitter reality Robin Lung was facing back in 2009.

The documentary, which had been so celebrated after its release in 1941, had simply vanished. It would be hard to profile the filmmaker if the film didn’t exist.

Lung had become a documentary filmmaker in her own right, after switching careers in her early 40s, and had recently discovered the late Li Ling Ai, a Chinese-American filmmaker from Hawaii, just like herself.

It was a detective story that led Lung to the woman she hoped would become the subject of her latest profile.

She had been on the hunt for a strong, Asian pop-culture figure, the kind that had been absent from her own childhood.

“There were many people in my everyday life who were admirable role models: teachers, politicians, doctors who were Asian women,” Lung recalled.

“But in popular culture, in movies and books, which I loved and consumed with a passion, those didn’t feature any Asian women who were strong, career-type women.”

In her home state of Hawaii, Lung was inspired to pursue stories of minority women that “hadn’t been given that much attention”.

She participated in documentaries about Japanese-American politician Patsy Mink and Liliuokalani, the last queen of Hawaii. But as she sought new stories, cultural differences proved to be an impediment.

“There is this sort of tradition in Asian cultures not to draw attention to oneself and not to brag about what your accomplishments are,” Lung explained. “People often felt like they didn’t have worthy enough stories to merit someone making a film about them or writing a story about them.”

In 2008, on the prowl for fresh ideas, Lung found herself devouring novels starring a spunky detective named Lily Wu. A strong Asian heroine, at last.

“I really wanted to find a woman who embodied that same spirit, that really strong, ambitious, creative spirit that the Lily Wu character had,” Lung said.

And she was in luck: author Juanita Sheridan hadn’t simply invented Lily Wu. She based her characters on real-life people. Struck by a reference in Sheridan’s novels to an Asian female doctor, Lung researched to see if any such doctors existed during Sheridan’s lifetime.

Li Ling Ai’s mother fitted the description, and Li had devoted an entire book to her parents’ medical work and activism. When Lung read Li’s biography on the book’s cover flap, she realised she might have found her Lily Wu.

Watch: China’s Wanda goes to Hollywood

Here was a woman who flaunted her Chinese heritage with silk gowns and intricate hairstyles, a woman whose talents seemed boundless. She was a published playwright, a noted dancer, a theatre director, a relief worker and even a “confidante” for the oddity franchise, Ripley’s Believe It Or Not.

There was a glint in Li’s eye as she stared up from the cover flap. And Lung was particularly struck by a line in her author biography: something about how Li Ling Ai had co-produced an Oscar-winning documentary entitled Kukan.

The night that award was announced became known for one of the biggest snubs in Oscar history. Director Orson Welles’ masterpiece Citizen Kane lost in almost every major category to the now largely forgotten drama How Green Was My Valley.

A dare: ‘Go where the real story is’

![Armed with a 16-millimetre Bolex camera, Scott travelled the length of China [NAS Fort Lauderdale Museum]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/a143f239f25047fc9f90f88f40cb41a8_6.jpeg)

But on that same night, on February 26, 1942, the Academy Awards made another historic decision. It awarded the first Oscars specifically for documentaries, a still evolving genre of cinema.

Fact and fiction were not so clearly defined back then. One of the top “documentaries” that year was written by the American novelist John Steinbeck. It depicted real-life Mexican villagers playing versions of themselves in a scripted drama.

There was another brand of documentary emerging, however, and it was rapidly gaining prestige. Kukan was part of a generation of war documentaries that sought to help American audiences understand the battles being fought overseas. World War II was well underway, and the US was wavering over whether to enter the fight.

This film is made at a time when documentary cinema was of great importance in the war mobilisation among the Allied Forces

Kukan had a backstory as compelling as its onscreen material. When a young newspaperman named Rey Scott set out to interview a Chinese dancer named Li Ling Ai, she issued him a challenge.

“Don’t waste your time here on this stuff. Go where the real story is,” Li said, according to a World-Telegram article printed about their meeting. News was trickling in that Shanghai had been shelled.

Li felt passionately that the attack on China merited more coverage. She had been forced to return home from Beijing because of the Japanese invasion, and her sister was still over there, helping with medical care. “There’s a boat sailing on Friday. I dare you to take it.”

Scenes of Chinese resistance

And with her help, he did.

Armed with a 16-millimetre Bolex camera, Scott travelled the length of China, capturing the fallout from the Japanese invasion.

He filmed scenes of resistance: Ethnic minorities uniting to fight; supply runners packing goatskin rafts; and factory workers dismantling their own workplace to save it from the Japanese.

He even managed to catch China’s Nationalist leader, Chiang Kai-shek, in a casual moment playing checkers.

When bombs poured down on Chongqing, the Nationalists’ wartime capital, he was there to film the explosions.

“Out of a blue sky roar the bombers, unloading their packages of death upon the riverside city, and then the yellow flames complete the terrible havoc as little men battle valiantly to check them,” New York Times critic Bosley Crowther wrote.

He praised the film as “crudely made but intensely interesting”.

Kukan was smuggled back to the United States, supposedly in bamboo poles, and there it was shown in some of the finest movie theatres on Broadway.

It even got a special White House screening.

The Oscars couldn’t possibly ignore a film with so much momentum. Though there was no category for feature-length documentaries in 1942, Kukan and another wartime documentary both won special awards.

Columbia University professor Ying Qian said that governments came to rely on the genre for propaganda purposes, since “its persuasive power is greater than fiction”.

“In some ways, this film Kukan was not a unique phenomenon. Many films were made at the time about the war and about the Chinese resistance,” Qian said.

“This film fits into this whole circulation of documentary filmmaking that’s international, that’s collaborative during the war. It really highlights the importance of war in the development of documentary.”

Forgotten female filmmakers

But film reels are delicate, and after World War II, there was little incentive to keep Kukan intact. World politics had shifted. The relationship between China and the US eroded as the Cold War took hold.

There was no market for an indie film that glorified China, especially after its Communist Party came to power.

Over half a century later, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences listed the film as lost.

Robin Lung had little hope of ever profiling the film and its makers.

A friend suggested that she pursue a documentary about Li Ling Ai’s parents, instead of trying to cobble one together about Li Ling Ai herself. But all the interviews she did inevitably turned to the late Chinese artist and the mysteries of her past.

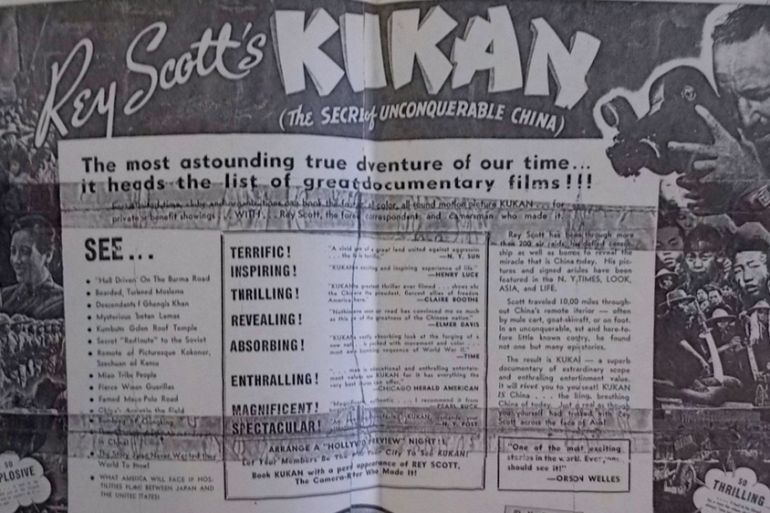

Li was only credited as a technical adviser on the film, while the mustachioed rogue Rey Scott was proudly displayed on all of Kukan’s promotional material. But it was becoming clear to Lung that they were partners in this venture, and very likely co-producers.

“I have no qualms about saying that she was a producer on the film, and a very strong producer,” Lung said. “I think that race and gender had everything to do with how she was treated.”

Read: Rewriting the role of Chinese women

It is a sentiment echoed by Professor Ying Qian.

“We don’t know what kind of dynamics [Scott and Li] had, or what happened, but the fact that she wasn’t highlighted probably had to do with the patriarchal structures in the film industry.”

Qian believes that being trans-national may have also contributed to Li’s diminished billing.

“We think about films largely in national terms,” she said, adding that other Chinese-American filmmakers, like Esther Eng, were similarly forgotten with the passage of time.

Lung was determined not to let the story of Li Ling Ai slip away. She kept pushing, asking more and more people about Li and Kukan.

“Some history people say, ‘Oh, lots of people didn’t get credited for what they did.’ But that doesn’t make it right,” Lung said.

Finding Kukan

But as it turns out, Lung wasn’t the only person rediscovering Li. On the opposite side of the country, at roughly the same time, Rey Scott’s granddaughter Michelle had stumbled across her too.

Among the photographs she found in that old box was a portrait of Li, gazing coolly into the camera. Her hair was adorned with an ornate metal headdress, and in her hand she carried a fan.

“Something drew me to her picture, and I just couldn’t get away from it,” Michelle remembered. “I was inspired to make a portrait, even though I had no idea who she was at all.”

Meanwhile, in 2009, Lung made a breakthrough. She had found a partial copy of Kukan in the US National Archives, but the situation wasn’t ideal. Only a third of the movie was preserved, and she had to find the owners of the copyright – Rey Scott’s heirs – in order to use the footage.

When Lung finally got in touch with Scott’s sons, they offered her more than she imagined. They gave her what might be the last remaining copy of Kukan. It had been deteriorating in one of their basements for decades, a few steps away from where Michelle Scott found the box of photographs.

“In my heart, I always wanted to do a documentary about Li Ling Ai,” Lung said. “When I actually discovered a copy of the film, I was all in for Li Ling Ai. I didn’t turn back.”

Preserving a community’s vanishing history

Finding Scott’s descendants led Lung to another discovery. She came across a striking multimedia painting while researching Scott’s family history online. The canvas was filled with orange and red acrylic, and its focal point was an enlarged, black-and-white photograph, depicting an Asian woman with a fan in hand and a headdress in her hair.

It was Michelle Scott’s portrait of Li Ling Ai.

Lung wove the painting into her upcoming documentary, Finding Kukan, due to be released in autumn 2016. She hopes the film will motivate others to preserve their community’s vanishing history, as she and Michelle are doing with their work.

“The point of the film is really to draw attention to all the history that’s being lost constantly,” Lung said. “So that’s something I hope to inspire other people to do.”

![Kukan was smuggled to the US, where it was shown in some of the finest movie theatres on Broadway [NAS Fort Lauderdale Museum]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/c7b81f72a2254ec5b3604b7ea91f8ce7_18.jpeg)