Red-flagging Canada’s children on no-fly lists

Nearly two dozen kids deemed flight security threats – with little recourse to remove the highly secretive designation.

Nearly two dozen children, some as young as six weeks old, have been red-flagged as airline threats by the Canadian government with little recourse to extricate themselves from a highly secretive no-fly list.

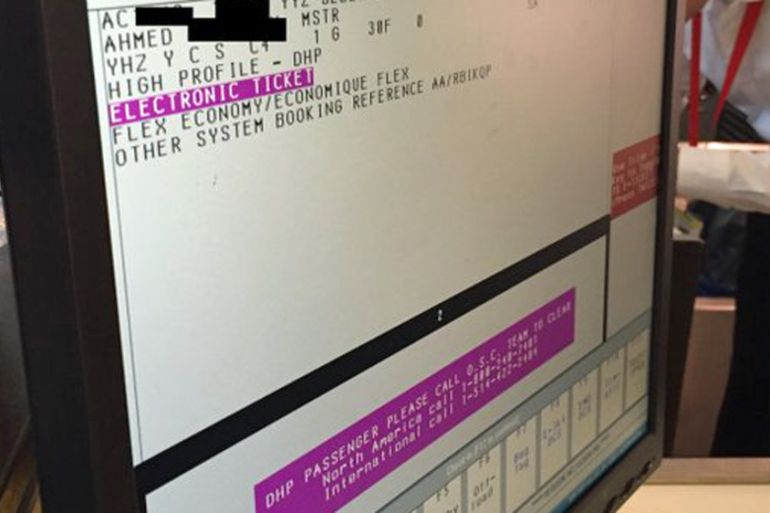

The embarrassing revelations for the government have come to light since January 1, after the father of Adam Ahmed, aged six, posted a photo of an airline computer screen showing his son listed as DHP – or “deemed high profile”.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsHong Kong’s first monkey virus case – what do we know about the B virus?

Why will low birthrate in Europe trigger ‘Staggering social change’?

The Max Planck Society must end its unconditional support for Israel

It was the latest in a dozen incidents in which Adam has been stopped for security checks before boarding a flight, with the first occurring when he was only six weeks old. His father, Sulemaan Ahmed, said that he hopes it will be the last time after his Twitter post drew significant media attention and other concerned parents came forward with similar stories.

He said on Wednesday that at least 21 children are now believed to be on the no-fly list, a number that keeps growing by the day.

“It’s a rainbow of colours,” Ahmed said, describing the ethnicities of red-flagged children. “And it’s not just kids with Muslim-sounding names.”

READ MORE: Canada pushes through anti-terror bill

Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale announced last week that the government will review the country’s no-fly list – formally known as the Passenger Protect Program – and he told airlines that children under 18 need not be held up in airports for extra security screening before boarding planes.

But the secrecy behind the mysterious no-fly listings has parents and rights activists concerned. It took years for Ahmed to finally be told that his son was even on the list. And even then, the news came from an airline employee, not the federal government.

Most disturbing, critics say, is the prospect of getting off the list once you’re on it. Even for these children, the road ahead to clear their names appears an arduous one – if not an impossibility.

Top secret

Little has been publicly disclosed about the machinations of the Passenger Protect Program. An estimated 500 to 2,000 Canadians are said to be listed as airline security threats and must be vetted before boarding any flights.

About 850 “false positives” – or people wrongly identified as security threats – were red-flagged from 2007 when the programme was launched until 2010. No data since that time has been made available.

The little that has been explained to Canadians comes from a 2010 parliamentary hearing with testimony from Laureen Kinney, the then director general of aviation security for Transport Canada.

“Normally, we do not supply the number of names on the list. We consider that information to be security-sensitive confidential information,” Kinney told the parliamentary committee. “It potentially could inform people who have malicious intent if they had a better idea of the number.”

|

|

| People & Power – Canada’s Lost Women |

Kinney explained that members of CSIS, Canada’s national intelligence agency, and the RCMP, its federal police force, decide who makes it on to the no-fly list.

“That information must have sufficient background, detail and provenance, if you will, to demonstrate clearly the concern that could be created if this person were to fly.

“The names that come forward for consideration deal with people who have demonstrated, in some fashion, the capability and intent to pose a threat to aviation security. Absolutely, it is not based in any way on ethnic, cultural, religious or other such factors,” said Kinney.

A meeting of the Orwellian-sounding “Ministry of Reconsideration” reviews the no-fly list every 30 days “without fail”, Kinney noted. That office then advises the public safety minister of any changes that could be made.

With such a clearly established protocol, critics say it’s hard to comprehend how children such as Adam Ahmed – mistakenly identified as security threats – still remain on the no-fly list years later.

Plethora of lists

Complicating the situation is the fact that a variety of other no-fly lists may be in play, said Kevin Miller, a spokesman from Public Safety Canada.

“It is important to recognise that there are many reasons individuals may not be allowed to board a flight or may experience delays at the airport that are unrelated to the Passenger Protect Program,” Miller told Al Jazeera in an email.

“For example, other countries, as well as airlines, maintain various security-related lists with different criteria and thresholds, which may result in delays for individuals traveling to, from, or even within Canada.”

Yves Duguay, president of security consulting firm HCiWorld, oversaw no-fly lists for Air Canada from 2000-2007. He told Al Jazeera that Canada’s system is similar to those around the world.

“The Passenger Protect Program is an important element or layer of the overall aviation security programme in Canada… The value of the PPP lies in its deterrent value,” he said.

READ MORE: Harper’s anti-terror obsession in unhealthy

But Duguay also highlighted the need for monitoring measures, adding “a balance must be found between preventing an interdicted person from boarding a plane and mitigating the impact of false positives”.

“The security value that is generated through this list can be reduced considerably in the absence of adequate controls and oversight to measure and demonstrate the level of compliance and performance for those tasked with the application,” he said in an email.

Monia Mazigh is the national coordinator of the Ottawa-based International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group.

She said it is impossible to know the effectiveness of no-fly lists since the government has failed to disclose any facts, and has so far refused public consultation.

Mazigh knows all too well the dangers of such lists. Her husband, Maher Arar, was mistakenly placed on a threat list and arrested in New York after the September 11 attacks.

Arar was one of the first victims of the CIA’s extraordinary rendition programme as he was suspected of being an al-Qaeda member and deported to Syria – where he was imprisoned and tortured for nearly a year before being returned to Canada.

A Canadian inquiry later found Arar had been a victim of “false and inflammatory information” given by the RCMP to the CIA.

Thirteen years later, it remains unclear if anything has changed. “We suspect that he’s still on this US list even today,” said Mazigh.

Jet Belgraver in Toronto contributed to this report

|

|

| Canada welcomes a new prime minister and a new foreign policy |