Brazil drought brews trouble for coffee farms

Global coffee prices set to rise as world’s biggest producer faces worst drought in living memory.

Tres Pontes, Brazil – Hugo Brito frowns as he examines berries plucked from a coffee bush on his family’s plantation. Opening one of the berries with a pocket knife, he shows a visitor what’s worrying him about this year’s crop.

“You see that these beans are not well-formed,” he says. “These beans should be bigger. Some of them are hardly developed at all.”

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsLost Futures

Photos: Greek valley that became a lake stirs drought debate

Botswana threatens to send 20,000 elephants to Germany

A drought – the worst in living memory – has struck Brazil’s coffee belt. Brito is of the fifth generation to operate the sprawling, thousand-hectare fazenda, or plantation, called Fazenda Santa Hedwirges. It’s located in the heart of coffee country, near the town of Tres Pontas, in the state of Minas Gerais.

Brazil is the world’s biggest producer of coffee. But since late last year, a severe drought has stunted growth on coffee plantations – in the heart of Brazil’s coffee-growing region. The price of coffee is set to rise as a result.

This is the growing season, but so far the rainfall has not been promising. “We had about 10 percent of what we are used to in this period,” Brito told Al Jazeera. “In December, January and February, we had just 10 percent.”

Feeling the pinch

All around Tres Pontas the coffee bushes stretch in orderly rows, covering the rolling hillsides and infrequent stretches of level land. This area grows the prized, high-quality Arabica beans favored by the big importers of coffee in the United States, Europe and Japan. Many of the beans grown on Fazenda Santa Hedwirges may wind up in a cappuccino savoured on the Piazza Navona in Rome, or in a low-fat triple caramel macchiato chugged by a busy commuter at a Seattle coffee chain.

If we have another dry season like this, I don't know what to do

To the untrained eye, the Arabica bushes on Brito’s fazenda appear green and glossy. But a closer look shows how the beans are shriveling up. Some of them have ripened to a deep red colour – far too soon before harvest time in June; others are completely black, dried up, and falling off the branches.

“They should be green now, and turning just a little bit yellow,” Brito says. “We have already the red beans, that are damaged, and these black ones will fall on the ground by the time we are ready to harvest.”

Nearby, labourers trimmed branches and cleaned debris from between the rows of coffee. Brito says he has no plans to lay off any workers. But as planters feel the economic pinch from the drought, it’s likely that farmworkers throughout the region will have fewer days to earn their small wages. That’s likely to strain their impoverished family finances even more than usual.

But the workers and growers aren’t the only ones who will suffer economically. Brazilian farmers say they’ll probably harvest about thirty percent less coffee than expected this year. And that means higher prices for coffee-drinkers all over the world.

‘Inferior quality, higher costs, higher prices’

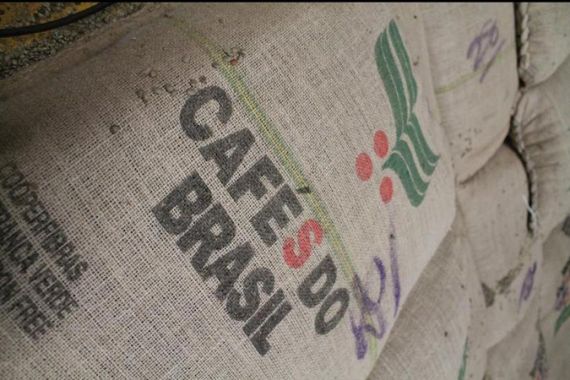

At the big coffee warehouse run by the farmers’ cooperative in Tres Pontas, burly workers heft 60-kilo burlap sacks full of dried beans. The men are dwarfed by towering piles of coffee bags. The warehouse complex can handle over a million bags at a time. It’s one sign of how dominant Brazil is to the world’s coffee trade. The country grows nearly 40 percent of global annual supply, far more than any other nation. But the drought will cut out a big piece of that production.

On the coffee commodity exchange in New York, fears of a drought-generated coffee shortfall caused the price for future deliveries of Arabica beans to surge more than 80 percent this year. The price for May coffee deliveries recently topped two dollars a pound.

In a whitewashed room dominated by roasting equipment and a round, marble-topped rotating table, a young assistant pours boiling water from an oversized aluminum kettle into twenty tiny glass cups of ground roasted coffee. Then it’s time for Alexandre Araujo to work his magic.

Araujo is a coffee degustador, or taster. He stirs and gently sniffs each steaming cup. Then, when the cups have cooled, he rapidly slurps up a spoonful of coffee from the cups arrayed in front of him, unceremoniously spitting out the sample into a giant spittoon. It’s Araujo’s job to determine the quality of each batch of coffee.

“Some people have a gift for it, but it also takes a lot of practice,” Araujo explains.

He also acts as a broker, matching coffee growers with buyers and exporters. As a veteran of the coffee trade, familiar with each step in the process that leads from bush to mug, Araujo has no trouble summing up the impact the Brazilian drought will have. “Inferior quality, higher costs for producers – and of course, higher prices for consumers,” he says.

It’s impossible to say for sure when the coffee shortage will start boosting consumer prices, or by how much. But, back on the fazenda, Hugo Brito says he can only hold out so long without rain. “If we have another dry season like this, I don’t know what to do.”